1912 Pfanschmidt murder case still cited today

A few years ago I read an

Illinois Supreme Court case, People v. Cruz (1994). I was surprised when the

court referred to an earlier case, People v. Pfanschmidt (1914). Was that the

Pfanschmidt murder case I had heard so much about growing up in Quincy — the

horrible murders out near the Haunted Tavern on the road to Payson?

Yes, it

was.

The Supreme Court in Cruz referred to Pfanschmidt, which held

that “testimony as to the trailing of either a man or an animal by a

blood-hound should never be admitted in evidence in any case.” Why? Because

“neither court nor jury can have any means of knowing why the dog does this

thing or another, in following in one direction instead of another; that must

be left to his instinct without knowing upon what it is based.” And there was

another reason, potential for prejudice. “It is well known that the exercise of

a mysterious power not possessed by human beings begets in the minds of many

people a superstitious awe.” The rule might be different where the dog actually

trailed and found a defendant who was independently shown to be involved in the

crime, but that was not the situation in Pfanschmidt.

On Sept. 27 or 28, 1912, Charles A. Pfanschmidt, his wife

Matilda, daughter Blanch, 14, and Emma Kaempen, a country school teacher

boarding with the Pfanschmidts, were brutally murdered at the Pfanschmidt home,

approximately five miles northwest of Payson. Their bodies were dismembered,

and the home set ablaze.

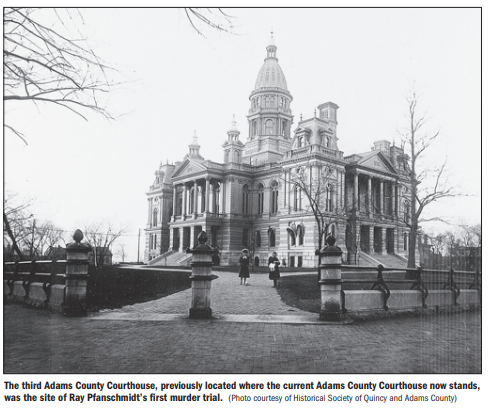

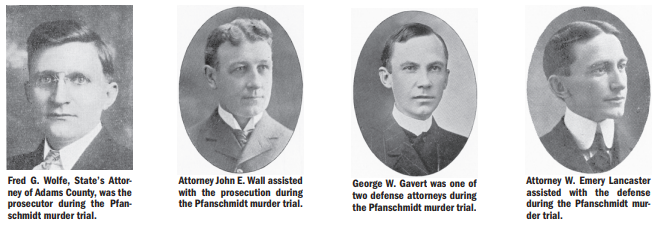

In January 1913, the Adams County grand jury returned four

murder indictments against the Pfanschmidts’ son Ray, 20. Tried for the murder

of his sister, Ray was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged on Oct. 18,

1913. On Feb. 21, 1914, the Illinois Supreme Court reversed that judgment and

remanded with directions to grant a change of venue.

Ray’s attorneys had sought a change of venue, supported by

120 affidavits of county residents stating that Ray could not get a fair trial

in Adams County. The state’s attorney then filed 2,251 affidavits in opposition

to a change of venue. The Supreme Court noted the decision did not depend on the

number of affidavits but whether there was a reasonable apprehension the

defendant could not receive a fair trial. The case had “aroused most intense

interest all over the county.” “Hundreds of people visited the scene of the

fire; some witnesses testifying that more than 200 automobiles were there that

day and several hundred buggies and wagons.” Four thousand people or more

attended the sale of the family’s personal effects. Many county residents had

openly condemned Ray’s attorneys for defending him. The sheriff had made

statements that the defendant was guilty and that many persons had asked for

the privilege of “springing the trap” at the execution. The state’s attorney

had opposed a change of venue, contending it would cost the county $20,000.

The Supreme Court also concluded the trial court erred in allowing the sheriff, deputy sheriff, and Detective Young to testify about statements they made in defendant’s presence, to which defendant did not respond. Said the court: “If the rules of law required him to talk, regardless of the advice of his attorneys, or answer questions or statements of the nature here put to him, or else it would be understood he was acquiescing, by his silence, in their truth, then the provision of our Bill of Rights that in all criminal prosecutions the accused shall be entitled to counsel is but an empty form.”

The dog-tracking testimony was interesting. Suspicious buggy and horse tracks were covered to protect them the day after the fire, while hundreds of people were visiting the scene. The next day, two dogs named “Nick Carter” and “Roger Williams” were brought to the scene. The owner testified that when he put Nick’s nose in the horseshoe track, Nick bayed, which the owner said indicated Nick had taken the scent. The owner testified Nick led him to the defendant’s camp north of Quincy on Twelfth Street. But the dog rode half the distance in an automobile, supposedly getting out to check the scent at each cross-road. At the defendant’s camp, Nick “lay down behind the horse which wore the shoe that it is alleged made the track in the Pfanschmidt barn lot.”

The trail the dog was supposed to follow was more than 30 hours old and had been disturbed by hundreds of autos and buggies coming and going along the Quincy and Payson road to the Pfanschmidt place. The defendant and his team had traveled the route before and after the murders. Some cases in other states have allowed dog-trailing testimony, but “in none of them were the difficulties and obstacles as the dog following the trail as many or as great as here.”

What followed is set out in a Quincy Herald-Whig story by staff writer Rodney Hart a few years ago. Ray was retried in Macomb and a “not guilty” verdict was returned. He then was tried in Princeton for the murder of his father, also resulting in a “not guilty” verdict. The state’s attorney decided not to proceed with further trials.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Pfanschmidt has been cited many times in recent cases, not just on the dog-tracking issue, but for the other holdings as well. And sometimes the courts are willing to listen to dogs. The U.S. Supreme Court has approved timely “canine sniffs” of luggage at an airport as a basis for issuance of a search warrant. Similarly, the police, during the course of a lawful traffic stop, may subject the exterior of a vehicle to a “sniff test” by a drug detection dog. If the dog alerts at the trunk, the officers have probable cause to then search the trunk.

The U.S. Supreme Court is currently considering another case, Florida v. Jardines, where the police brought a dog to the front porch of a home, the dog reacted to the scent of narcotics, the police obtained a search warrant, and marijuana was found growing inside the home.

The Florida Supreme Court viewed the “sniff test” as a substantial government intrusion into the sanctity of the home, which should not be allowed without an evidentiary showing of wrongdoing and a search warrant. The case is scheduled to be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court this season.

Robert Cook, a longtime resident of Quincy, is a judge on the Illinois Appellate Court in Springfield. He is a member of the Board of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources

Hart, Rodney. "100-year-old murder mystery a story begging to be told." Quincy Herald-Whig, September 13, 2011.

People v. Pfanschmidt. 262 Ill. 411 (1914).

People v. Cruz. 162 Ill. 2d 314 (1994).