A Chinese Puzzle: Identity theft not a modern problem as 1906 event shows

In February 1906, a murder in Quincy’s small Chinese community was likely the consequence of a case of stolen identity. Although local residents of Chinese descent were few in number, they owned several laundries and a restaurant in town. Sometimes called ‘‘celestials,’’ as China was often referred to the “Celestial Kingdom,” the immigrants maintained a low profile in our largely Germanic city. Trouble was brewing between China and the Western world, and in the American West there had been violence between miners unions and Chinese laborers brought in to attempt to break the unions, so our cautious local community of Chinese people preferred not to be noticed.

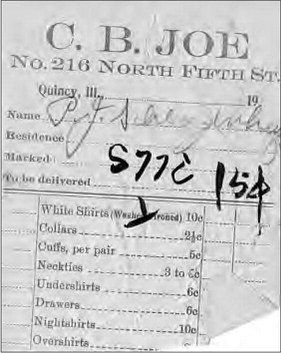

C. B. “Charley” Joe owned a laundry business at 215 N. Fifth and for two years had also run the Chop Suey Restaurant around the corner at 519 Hampshire. Business was doing so well that Charley was thinking of selling the little frame structure and building a much larger and better appointed café. It was rumored that he would spend $10,000-$12,000 on its construction.

But before that could happen, he was gunned down. The culprit was a fellow immigrant whom Charley had been helping.

About 9:30 p.m. Feb. 23, 1906, Ong Hong entered the Chop Suey restaurant, walked to the kitchen at the rear of the building, and shot Charley Joe. The wounded man ran out into the street. The assailant followed, shooting him twice more. Patrolman Thomas, at the corner of Sixth and Hampshire, heard the second shot and came running.

Patrolman Thomas ran past the fallen victim, entered the restaurant, “and took a rather tall and excited Chinaman, who still held the smoking pistol in his trembling hand, into custody.” The perpetrator offered no resistance and was led less than a block to the temporary police station to be booked. At that time the police were operating out of a storeroom in the Moeller Building at 306 Hampshire following the fire which had destroyed City Hall in January of that same year.

Charley was carried back inside the restaurant but died without speaking. An autopsy would show that the last bullet went through his heart.

Miss Cornelia Burner of South Fifth Street witnessed the shooting. She had been working as a waitress or cashier at the eatery. Miss Burner claimed the two countrymen were friends saying, “I have never known of any trouble between them.” She ran from the building at the first shot.

Once booked into the jail, the prisoner was visited by his uncle Yo Hong who ran a laundry (also on Hampshire Street between Seventh and Eighth streets) and a cousin Joe Jew (sic). The pair tried to translate for the authorities but their English was apparently not up to the job. Yo Hong then sent for a better linguist, Joe Sun, who finally arrived and translated the story.

Ong, the shooter, said he arrived in Quincy six or seven months previously, but he was sick when he came. Charley had taken him to a succession of doctors in search of a cure. Dr. Kelly and Dr. Johnson refused to treat him for what was described as a ‘loathsome disease,’ but Dr. Justice agreed to begin treatment, as a personal favor to Charley.

According to his story, Ong became increasingly nervous and suspicious of the treatments and suspected that Charley was paying the doctor to poison him. Dr. Justice dropped Ong as a patient when he refused to take the medicine.

Ong said that the thought of killing Charley had been on his mind for more than a month before he used a .38 Ivers-Johnson to shoot his benefactor. He stated that he had brought the gun with him from St. Louis.

Charley Joe had been a friend of detective George Koch. Koch said Charley had come to Quincy 14 years earlier and opened a laundry. At the time of his death, Charley owned half interest in a laundry with his cousin, Joe Sun, and had been operating the successful restaurant for two years. Charley Joe was 37 years old, a naturalized citizen, and at the suggestion of Koch, Charley had cut off his queue. Severing that long braid signified that his allegiance was now with his new country and that he never would return to China. He was committed to being

American. Ong Hong had also come to the U.S. 14 years ago, but it was rumored that he was a member of the notorious Highbinders gang. The Highbinders were part of a secret organization of Chinese gangs that began in San Francisco. It was said that they lived by blackmail and murder for hire.

Once in jail, Ong wrote a letter in Chinese characters and asked Sheriff Ed Smith to deliver it to Joe Sun. The Sheriff was perplexed, as he could not read the contents. It would later be discovered that the prisoner was only asking for tobacco.

On Saturday, two other “celestials” arrived in town. Joe Sing, uncle of the slain Charley Joe arrived from Carrollton, and accompanied by Koch went to the Freiberg morgue and viewed the body of his nephew. It was reported that he stood over the body and conversed in the Chinese language with the spirit of the deceased. After bowing his head and backing away, he reportedly said that, “a bad man had killed his nephew.” Charley was buried in Graceland Cemetery.

The other arrival was N. W. Gow from Chicago, who was a friend of Ong Hung and came to help and interpret. Gow said the correct spelling of the inmate’s name was “Hung.”

Evidence then surfaced from two years prior when the U.S. authorities were enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Law. This law, originally passed in 1882, extended and then made permanent as the Geary Act, prohibited immigration of Chinese “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining.” It also required each Chinese resident to register and obtain a “certificate of residence.” Without papers any oriental faced deportation.

Charley had been robbed of his citizenship papers, and was justly worried about being expelled from the U.S. if he couldn’t supply them. He applied for a new copy of his documents, on the advice of Koch. While investigating this application, the U. S. Secret Service discovered a second Charley Joe living and working in St. Louis. It was determined that only one ‘Charley Joe’ had qualified for citizenship, and a photo of the St. Louis man was obtained and brought to Quincy by a U.S. marshal.

It was soon determined that the bogus Charley Joe was the one in St. Louis, operating under the stolen papers. It was further revealed that the counterfeit was a cousin of both Charley Joe and Ong Hung. The Quincy Charley Joe had been taken to St. Louis to testify in the deportation trial of the imposter, who was sent back to China in disgrace. It was believed that this was the point at which Ong Hung decided to murder Charley Joe in retribution. Ong, however, steadfastly maintained his motive was fear of being poisoned.

At all of the official proceedings Ong Hung was twitchy and nervous. His feet literally danced, and he sat with his back to the judge’s bench, conversing in Chinese with Gow. After Ong pleaded “not guilty” at his preliminary hearing, the judge set trial for the next day.

That morning, Ong Hung appeared, and changed his plea to “Guilty.” Judge Aikers sentenced him to life imprisonment at the Chester penitentiary. But he didn’t last long in prison.

On Dec. 13, 1906, the warden at Chester prison contacted the only relative he could find of Ong Hung, saying the prisoner had died and requesting this Quincy relative to claim the body for burial. The relative, John W. Tai, who owned a laundry on Fifth Street, declined absolutely. A reporter for one paper wrote that few of the Chinese colony in this city would speak with him. The one who would, called “little Joe,” said of Hung, “He was a bad man and he hurts the Chinese. We will not have his body here.”

So ends in mystery the motive for killing Charley Joe. The most likely story remains that it was retribution for exposing and deporting a man who had stolen the victim’s identity.

Beth House Lane is executive director of the Historical Society, author of “Lies Told Under Oath,” the true story of the Pfanschmidt murders near Payson, and a facilitator of writing workshops in Quincy.