A look at the city's early Italian community

Most of the first Italian

immigrants to Quincy arrived between 1901 and 1910, when more than 2 million

Italians entered the United States. About 40 percent of these Italians were

“birds of passage,” coming to this country to earn money and then returning to

their families, or seasonal workers seeking opportunity in manufacturing during

holidays and peak times before returning.

Most Italians lived in large cities of the Northeast forming

“Little Italy” neighborhoods. Relatively few came to the Midwest or Western

states. Because agricultural conditions had been extremely harsh in Italy and

the grueling work done mostly by peasants under cruel landlords, even fewer

wanted to farm.

So how did an Italian community become established in Quincy

in the early 1900s with several families continuing with farming? Although some

families from Italy were already living in Quincy, such as the Musolinos and

Bonansingas, many of these first immigrants were from the region of Sicily and

left their homeland after a massive earthquake in 1908.

It was the worst

earthquake in European history and killed 110,000 people along the Messina

Straits, including several relatives of the Italians coming to Quincy.

These immigrants found it

easier to enter this country through the port of New Orleans rather than Ellis

Island in New York City. Standards were more lax, detention times shorter, and

language confusion eased with fewer immigrants using the port.

From New Orleans they boarded boats heading north up the

Mississippi River to relocate in a community that would, if not embrace, at

least be civil to largely illiterate people speaking only a few words of

English and knowing nothing of the culture. Tension existed between different

immigrant ethnic groups in America but far less in small Midwestern towns like

Quincy.

Many located here, too, because they did not have the means to travel

further from the Mississippi. Quincy may not have been Shangri La, but perhaps

you could earn your daily bread here.

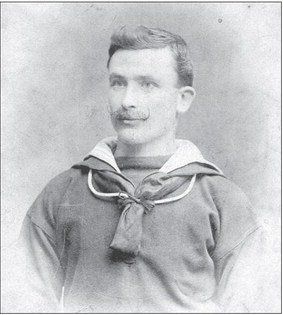

Among Quincy’s first Italian arrivals was Giuseppe “Joseph”

Affre, who had served in the Italian navy and liked living near water because

he could supplement meals with fresh fish from the river. He and his wife

Antoinette Anerino Affre were contradini — peasant farmers — and in Quincy they

cultivated a two acre plot of land they sharecropped and later bought, raising

produce at what is now the northwest corner of 36th and State Street.

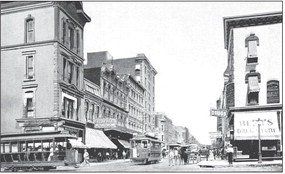

The Affres began selling their vegetables and herbs at a market stand that later became a store between Seventh and Eighth on State Street. Their home was next door at 429 S. Seventh. At a time when the city was becoming more industrialized and people had less time for gardening, Quincyans welcomed the fresh produce the Affres provided at their store and with their home delivery route.

Once word got back to Italy about the opportunities here, other family members and more Italian households followed. By the beginning of America’s involvement in World War I in 1917, three of Joseph’s brothers and an assortment of relatives and other Italian-born citizens had made Quincy their new home. In 1925 the Gem City had a small but thriving Italian community of about 200 people centered in the Eighth and State area pursuing the American Dream while maintaining a strong sense of national origin. They continued following many Italian traditions including meals, religious practices, dress, and speaking Italian among themselves.

When Joseph Affre died in 1932 at the age of 46, his wife and children continued farming and running the family store until about 1945, when World War II sent their boys to war and the girls opted for careers other than living off the land. Joseph’s brother, Giovanni “John” Affre, along with his wife Venera and his daughters Angela and Josephine had a similar market at 609 Hampshire that was in business for 64 years.

Retirement was unheard of for these immigrants: John worked until his death at age 92.

Immigrant Italian-born males in Quincy were almost all self-employed, largely because of language barriers and reluctance by employers to hire workers so unfamiliar with the way of life. Wives helped their husbands and were homemakers: Italian culture made that a woman’s role. They were hard-working and industrious and frugal and did very well here.

Traditional Italian values followed these first immigrants to this country. La familgia (the family) is the sense of duty to relatives and other Italians in the community, and it ran as deep as the Mississippi. A girl born totally deaf was cared for even as an adult with the tenderness of a child. Families cared for their elderly at home. Nursing homes were not part of that day’s Italian culture.

No ethnic group dovetails without some rough edges into an adopted country. Two of the more startling areas of conflict for Italian-Americans in Quincy and elsewhere were religion and education.

These first immigrants to Quincy and almost all Italians at that time were Roman Catholics, but it was strikingly different Catholicism than that practiced in this country. The Italians often venerated individual saints with a devotion many Catholics here considered superstitious and unsettling. Some members of the church found the Italian behavior of warding off such things as an “evil eye” or malocchio disturbing, if not bizarre. Evil eye is the belief that a person’s expression can convey jealousy or envy and do harm to the receiver of these looks. It was combated by practices such as wearing a pouch around the neck with a bulb of garlic in it or sprinkling sesame seeds on a plate before eating.

Education was the key for the next generation to becoming more a part of this culture and living with less hardship than their parents. Some ethnic factors, though, worked against Italian-born citizens embracing education for their children. First, it threatened the authority of the parents by giving children “brash ideas.” Also, at that time children — especially males — were needed to help put food on the table. Even the school lunch program clashed with Italian values because it took children away from the traditional calazione — families eating lunch together.

Those first generation Italian-Americans growing up in Quincy, though, became enthusiastic members of Quincy society while preserving many of their ethnic virtues. They never forgot their roots.

Our family gathered when my great-grandmother’s first grandchild was born. She kept saying, “la bella bambino! (the beautiful baby boy!) When he grows up he will be pope!” The child’s mother piped up, “When he grows up he will be president!” My greatgrandmother paused long before saying, “As long as he doesn’t forget where he’s from.” A poignant silence followed. Finally someone in the room asked sheepishly, “Where is that?” A wave of voices rose from the shores of history and hope and hard-won wisdom, “The United States — it’s a suburb of Italy!”

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer and photographer. He has written for the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project and the Illinois Veterans Home magazine “Bugle” for the past 19 years and published essays, poetry, travel stories, and biographies in literary magazines and journals.

Sources

"A Lifetime on Hampshire Street." Quincy Herald-Whig, August 11, 1968. (about the life of John Affre)

"Anxious Days for Italians." The Quincy Daily Journal, December 30, 1908. (about the massive earthquake in Messina, Sicily in 1908)

Bacigalupo, Leonard F. OFM. The Franciscans and Italian Immigration in America. Hicksville, NY: Exposition Press, 1977.

Daniels, Roger. Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1990.

Greene, Victor. A Singing Ambivalence: American Immigrants Between Old World and New, 1830-1930. Kent, England: The Kent State University Press, 2004.

Jones, Maldwyn Allen. American Immigration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Jones, Maldwyn. Destination America. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976.

Kraut, Alan M. The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880-1921. Arlington Heights, Illinoi: Harlan Davidson, Inc., 1982.

Landrum, Carl. "From Quincy's Past," Quincy Herald-Whig, August 26, 1984. (Vincent Affre biography)

Obituary of John Affre. Quincy Herald-Whig, January 15, 1970.

Obituary of Venera Affre. Quincy Herald-Whig, May 5, 1967.

"Pete Affre: A Manner, philosophy all his own." Quincy Herald-Whig, June 4, 1973.

"Peter V. Affre dies; well- known coach." Quincy Herald-Whig, October 20, 1980.

Rolle, Andrew. The Italian Americans: Troubled Roots. New York: The Free Press, a Division of Macmillan Pub. Co. Inc., 1980.

"Romantic Wedding at St. Peter." The Quincy Daily Journal, January 17, 1912. (about the wedding of John Affre and Venera)

Tomas, Silvano and Madeline H. Engel ed. The Italian Experience in the United States. Staten Island, NY: Center for Migration Studies Inc., 1970.

"Wedded at St. Peter's." The Quincy Daily Journal, December 30, 1908. (about the wedding of Joseph Affre and Antoinette Anerino)

Wheeler, Thomas C. ed. The Immigrant Experience: The Anguish of Becoming American. Baltimore, Maryland: Penguin Books, Inc., 1971.