A Tale of One Village: Stone’s Prairie Becomes Plainville

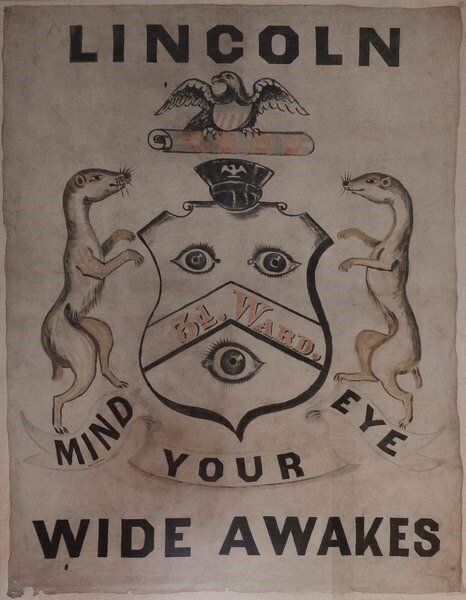

This banner hangs in The Old Capitol building in Springfield, IL. It was created by the Wide Awakes, a Republican organization that was active during the 1860 presidential election. It shows three eyes on a pseudo-heraldic shield, with slogan "Mind your eye". (Courtesy of WikiMedia Commons)

In Ruth Deters’s book, “The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House!” she reprinted the 1910 obituary of Rev. Abraham T. Stone, age ninety-two, described by the Quincy Daily Journal as “one of the sturdy pioneers of this vicinity.” He had arrived at age four in 1822 and, with his parents and three siblings, established their homestead in what became Stone’s Prairie, seventeen miles southeast of Quincy. Their four-week journey from Licking County, Ohio, by wagon had been difficult, with rain every day but three.

Abraham’s father, Rev. Samuel Stone, was, the Herald Whig wrote in 1929, an early Methodist circuit rider in Western Illinois who served as pastor of Akers Chapel, south of Stone’s Prairie. Abraham married Mary Ann Lippincott and followed his father into the ministry after studying with the abolitionist leader Rev. David Nelson of Quincy.

Abraham later recalled “the effect of solitude” on his childhood in this place with neighbors very distant. Yet little more than a century after his family arrived, Stone’s Prairie had become Plainville, with a post office, school, two churches, two grocery stores, bank, hardware store, barber shop, gas station, welding shop, and softball field. On Saturday nights, well into the 1960s, farm families came into town, not to shop, but “to do their trading”. Among its future residents were a blacksmith, seamstress, doctor, piano teacher, two housepainters, a family of carpenters, a ten-time Illinois State Fair horseshoe-pitching champion, and softball players who might have welcomed Abraham Stone to the team.

Probably the outside world first noticed the community in 1860 after the “Stone’s Prairie Riot.” As described by Iris Nelson and Walter Waggoner, a “Republican organized political rally [went] awry” in the “bitterly contested” presidential election between Abraham Lincoln and his Democratic party rival, Stephen A. Douglas. Their article quotes the Chicago Tribune’s account of a camp-ground assembly south of town as “one of the most extraordinary gatherings of people that has ever taken place in this part of the state.”

“Profound divisions” among Adams County residents, Nelson and Waggoner wrote, “existed among residents over the future course of the country” and the presence of slavery. Ruth Deters described how New England Congregational abolitionists founded Payson, Illinois, in the midst of settlers from Southern states who, while perhaps not pro-slavery, were nevertheless hostile to Adams County’s Underground Railroad. Many voters in the Stone’s Prairie area favored Douglas, the Democratic candidate for President, who, as a judge in Quincy, had convicted Dr. Richard Eells for harboring a runaway slave.

On August 25, 1860, supporters of Lincoln, called “Wide Awakes,” marched three miles from Payson to the rally, where Orville H. Browning, Quincy lawyer and prominent Lincoln supporter, was among the speakers. The Barry, Illinois, Glee Club sang, and many families brought their picnic baskets. As Nelson and Waggoner wrote: “Almost all observers commented on the large amounts of alcohol consumed. It was so bad that sobriety at Stone’s Prairie may have been the exception rather than the rule.”

Estimates of crowd size ranged from 7,000 to10,000. When Douglas’s supporters interrupted Browning’s address because they were not allowed to present an opposing speaker, the fighting began. In the 1860 election, Douglas, who opposed Lincoln but supported the Union, carried Stone’s Prairie and nearby areas.

Stone’s Prairie men served in the Union Army under Gen. William T. Sherman in Western Theatre battles, eventually supporting troops under Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the capture of the Vicksburg fortress on July 4, 1863, thereby opening the Mississippi River to Northern commerce. After a battle at Chattanooga, they marched with Sherman through Georgia to capture Atlanta on September 2, 1864. A Stone’s Prairie soldier, James Buck, was killed on October 5, at Allatoona, Georgia, before Sherman’s troops reached the Atlantic Ocean on December 21.

The 1879 History of Adams County commented, “There has sprung up a thrifty young village on Stone’s Prairie, called Plainville, or more improperly called Shakerag, and by all appearances quite a business place.” The Stone’s Prairie post office was established January 29, 1856, but by July 23, 1893, residents had obtained a change of name to Plainville, honoring postmaster and merchant John Delaplain. They incorporated the town as Plainville on May 1, 1896.

The name “Stone’s Prairie” endured, however. When Abraham Stone’s daughter, Sarah Amanda Putman, died in 1929, the Herald Whig wrote that she had been born April 2, 1844 in Plainville “when that village was known as Stone’s Prairie,” and that “as one of the oldest native-born residents of Adams County,” she “could relate stories of pioneer days in Plainville when Adams County was emerging from its wilderness stage.”

In 1930 the newspaper reported probate of the “will of William H. Stone, Sr., of Plainville, for whose ancestors the country south of the village was named ‘Stone’s Prairie,’ a name by which it is still known….” Also in 1930, the obituary of Gilbert Vance Stewart, a son of Irish immigrants who arrived in Stone’s Prairie in 1837, identified his lifelong home as “half a mile south of Plainville.” Those descriptions suggest a distinction between the physical legal boundaries of Plainville and the unofficial dimensions of the Stone’s Prairie settlement.

Through the 1950’s, a siren sounded, six days a week by the postmistress signaling the noon hour. Only the operators in telephone central, located in the former bank building, were allowed access to the siren at other times, and those alerts summoned the volunteer firefighters.

On one Plainville street lived three women born in the 1870’s. A boy interested in history asked one if she remembered people in town talking about the Civil War as she grew up. She replied “Yes,” and added that there were stories that the father of another resident still living in town had been a Confederate sympathizer, stealing horses and delivering them to rebel guerillas in Missouri. She did not explain how he got the horses across the Mississippi River. Was her story true, or was she just entertaining a neighbor’s pesky child?

Kent Hull, a retired lawyer living in South Bend, IN, is a long-distance member of the Historical Society. He grew up in Plainville and graduated from Seymour High in Payson, Illinois.

Sources

Deters, Ruth, “The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House!” Quincy, IL: Eleven Oaks Publishing, 2008, 112-113.

“G.V. Stewart, 76, Lifelong County Resident is Dead.” Quincy Herald Whig,

November 28, 1930, 12.

“History of Adams County Containing a History of the County...” Chicago, IL: Murray, Williamson, and Phelps, 1879, 552-553.

Mayfield, Linda Riggs. “Payson Township: Two Towns, Many Schools and Fruit

Trees.” Quincy Herald Whig, November 17, 2019.

“Mrs. Putman, One of the County’s Oldest Natives, is Dead,” Quincy Herald Whig, June 2,

1929, 20.

Nelson, Iris A., and Walter S. Waggoner. '"Sick, sore and sorry': The Stone's Prairie. Riot of

1860," Journal of Illinois History 5, (Spring 2002): 19-32.

“Company "D" 50th Illinois Infantry,” https://civilwar.illinoisgenweb.org/r050/050-d-in.html

“Two Wills are Placed on File to be Probated.” Quincy Her