Abraham Lincoln had many Quincy connections

Today a grateful nation observes the 203rd anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, and Quincy can celebrate his many close connections with our community.

It is likely that Lincoln first made the acquaintance of Quincyans in 1832 during the Black Hawk War, 10 years after John Wood settled in Quincy and while Lincoln called New Salem home. Militia units from both areas met near Rushville in response to Gov. Reynolds’ call for 1,500 mounted volunteers and served in the campaign.

In 1834 Lincoln joined Archibald Williams, representing Quincy, in the Illinois House of Representatives in Vandalia. In 1836 Lincoln met newly elected Sen. Orville H. Browning and his wife Eliza. Their close personal friendship would last until Lincoln’s assassination. Eliza became Lincoln’s confidante and social mentor, beginning what turned into Lincoln’s longest-lasting female relationship. Other Quincyans including Abraham Jonas, Jackson Grimshaw, Isaac N. Morris, and James W. Singleton and soon-to-be Quincyan Stephen A. Douglas were elected to the state legislature in the 1830s and 1840s and became friends and political allies or opponents of Lincoln. Andrew Johnston, assistant clerk of the Illinois House, was later one of the first editors of the Quincy Whig. “Friend Johnston” published some of Lincoln’s poetry.

“The Lincoln Log: A Daily Chronology of the Life of Abraham Lincoln” reveals a regular flow of communication between Lincoln and Quincyans – about shared law cases, politics, political appointments, and personal friendships. Many were close relationships as demonstrated by confidential letters to Eliza Browning and Lincoln’s reference to Jonas as “one of my most valued friends.” At times the historical importance is evident. Henry Asbury, a frequent correspondent with Lincoln, framed four questions which Lincoln put to Douglas during the 1858 Freeport debate.

“The Lincoln Log” also indicates that Lincoln visited Quincy more often than many realize, traveling to Quincy on the way to and from St. Joseph, Mo., and Council Bluffs, Iowa, twice in 1859 and again in 1859 on the way home from railroad business in Hannibal, Mo. There are also unsubstantiated stories about Lincoln visits to Quincy and Adams County, and one can only speculate about his trips here before he was in the public eye.

Lincoln’s first documented visit to Quincy occurred in 1854 when he spoke on behalf of his Quincy friend “Archie” Williams, “Free Soil” candidate for Congress. Lincoln had withdrawn from politics, but the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened to slavery an area that had been guaranteed free for 34 years and brought Lincoln out of retirement. Lincoln attacked the new law and Stephen A. Douglas during his speech in Quincy’s Kendall Hall. Soon local politicians were working with Lincoln to found the new Republican Party. Most Whigs and some Democrats became Republicans from 1854-1856.

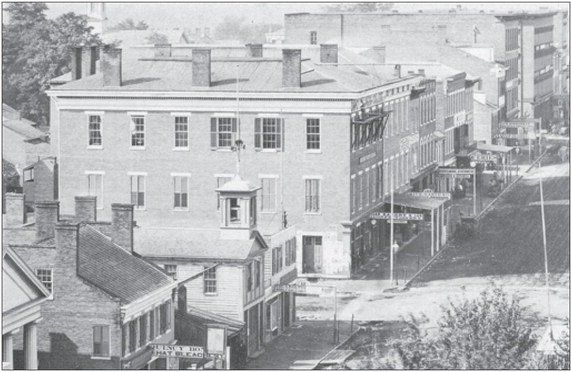

The Oct. 13, 1858, Lincoln-Douglas Debate was probably the most significant national event ever to occur in Quincy. Held downtown in Washington Park, it was witnessed by thousands of spectators from Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri and lasted three hours. Lincoln took his strongest stand, yet, against slavery and argued that “it is a moral, a social, and a political wrong …” while Douglas stated that slavery was not a moral issue and reasoned that states “… can exist forever divided into free and slave states …” The Lincoln-Douglas Debates resulted in the reelection of Douglas as senator but catapulted Lincoln into national attention and led to his election as president.

In December, local Republican leaders met with Horace Greeley, anti-slavery editor of the New York Tribune, in the Quincy law office of Asbury and Jonas. Asbury suggested Lincoln for the presidency, one of the earliest to do so. Soon Quincyans took important roles in helping Lincoln win nomination. Grimshaw, a member of the Republican State Committee, helped to secure Lincoln’s consent to be Illinois’ favorite son candidate at the national convention. Jonas worked the convention floor and helped pack the hall with Lincoln supporters, whose additional enthusiasm led to Lincoln’s nomination. Browning was chosen to give the convention speech thanking the delegates, and he also worked behind the scenes after the nomination to unify the party behind Lincoln.

During the 1860 presidential campaign, Gov. Wood invited Lincoln to use the governor’s office in the State House, and Lincoln made it his campaign headquarters. Lincoln’s Quincy friends campaigned for him and supported him all the way to the White House. President-elect Lincoln discussed the secession crisis freely with Browning but few others. Browning and Grimshaw rode on the inaugural train with Lincoln as far as Indianapolis. Lincoln asked Browning to review his inaugural address and took Browning’s advice to soften its tone.

President Lincoln named many Quincyans to government and military positions, using their talents to help his administration and the Union. Browning visited the White House frequently and promoted those local appointments. While other Quincyans were regular visitors, the Brownings were more like family. Orville helped make the funeral arrangements, and he and his wife “received for the family” when Lincoln’s son, Willie, died in 1862. Eliza stayed two weeks at the White House to help deal with the personal grief and Tad’s care.

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theater and was carried across the street to the Peterson House, where he died. Col. George V. Rutherford of Quincy guarded Lincoln’s body, placed coins on his eyes, and escorted the body to the White House. Browning was the only non-medical civilian present for the autopsy. He helped plan Lincoln’s funeral and served as a pall bearer at Mrs. Lincoln’s request.

When the telegraphed news of Lincoln’s death arrived, Wood and three others rushed to the Congregational Church to ring the historic bell that had once hung in the Lord’s Barn. Soon the community turned from shock to mourning. City council rooms and Quincy streets were draped in black, citizens wore crepe, saloons and many businesses closed, churches had special services, and Wood presided over a mass meeting on Washington Square. Many Quincyans attended Lincoln’s funeral in Springfield, requiring an “extra train with 19 full cars.”

Wood and Grimshaw soon led the widely supported Adams County drive to fund the Lincoln Memorial in Springfield. The later acquisition of the assassination artifacts now on display in the Historical Society’s Lincoln Gallery was made possible by Lincoln’s close associations with Quincyans like Asbury and Browning.

Readers interested in learning more about Lincoln’s ties to Quincy can find additional information in the “Quincy in the Lincoln Era” exhibit in the Lincoln Gallery, in Quincy’s 18 Looking for Lincoln Wayside Exhibits and at the Lincoln-Douglas Debate Interpretive Center. “The Lincoln Heritage Trail” brochure includes a map and list of the LFL wayside exhibits and Quincy’s Lincoln sites and is available at the Historical Society and the Interpretive Center.

Chuck Radel is retired from the Quincy Public Schools and taught history for 20 years. He is a local historian, president of the Historical Society, and a member of the Lincoln-Douglas Debate Interpretive Center Advisory Board.

Sources

"Accession Record of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois." Accession No. C389 a-d, undated.

Costigan, David, "A City in Wartime: Quincy, Illinois and the Civil War." PhD dissertation, Illinois State University, 1994.

Looking for Lincoln Wayside Exhibits in Quincy. 18 storyboards. Springfield: Looking for Lincoln Heritage Coalition, 2009.

Papers of Abraham Lincoln. "The Lincoln Log: A Daily Chronology of the Life of Abraham Lincoln." http://www.thelincolnlog.org .

Pease, Theodore Calvin; and James G. Randall (eds.) (1925-1913). The Diary of Orville H. Browning, 1850-1881 (2 vols. ed.). Springfield, Ill.: Illinois State Historical Society. The diary is also available online at http://www.archive.org/details/diaryoforvillehi20brow .

Quincy Daily Herald. Passim.

Quincy Herald-Whig, February 12, 1950.

Quincy Daily Whig. Passim.

Quincy Daily Whig and Republican. Passim.

Quincy Whig. Passim.

"Quincy: The Lincoln Era; Politics and the Lincoln Presidency." Exhibit in the Lincoln Gallery, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, 2010.

Whitney, Ellen. M., comp and ed. Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library, Vol. XXXVI; or, The Black Hawk War 1831-1832; Vol. II, Letters and Papers; Part I, April 30, 1831-June 23, 1832. Springfield: Trustees of the Illinois State Historical Library, 1973. (1297-1298)