Accomplished Quincy man was unlucky in love

For 46 years, Quincy was home to Addison Langdon, a man of many accomplishments, and by his own account, had terrible luck with women.

His obituary in The Quincy Daily Herald from 1923 lists many of his activities between his arrival from Chicago in 1857 and when he left Quincy in 1903. He was, at one time or another, a newspaper editor; publisher of four city directories and six histories of Quincy as well as one of Adams County; secretary for the county Republican central committee; city oil inspector; secretary of the Gem City Telegraph Institute, an employee of the Internal Revenue Service; manager of the opera house and the Tremont Hotel; and he founded the Quincy Commercial Review, which later became the Saturday Review, a newspaper catering to local entertainment interests.

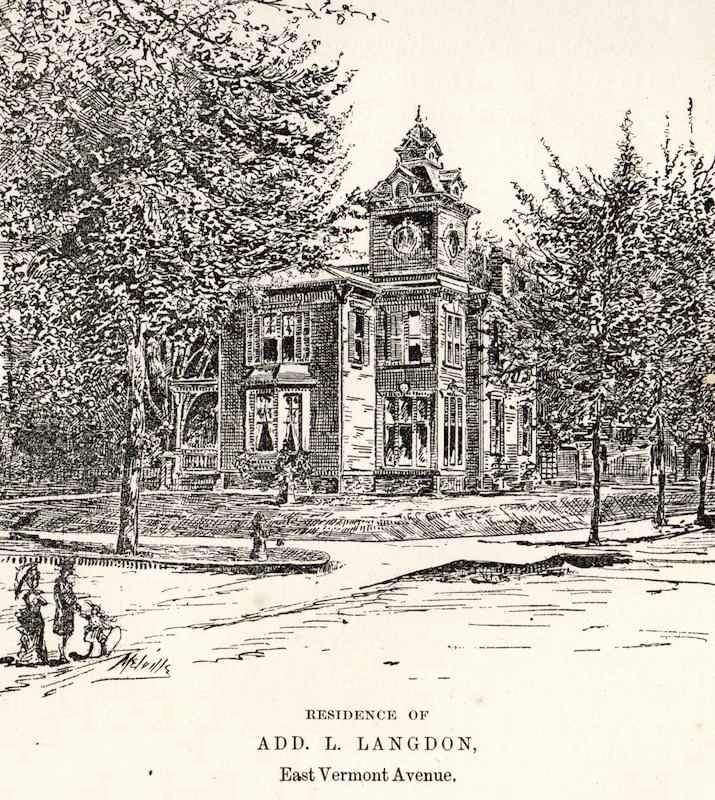

Langdon came to town after his brother, James Langdon, purchased The Quincy Whig. By 1869 Addison Langdon was prospering, and he married Sophronia Vanderberg Sullivan. He built a beautiful home at 16th and Vermont, with all of the conveniences, spending the then considerable sum of $12,000 on the house. But his life came crashing down when Sophronia died in May 1878. Langdon said in 1912, "…from that day until the present hour everything has gone wrong, always to my detriment and injury."

Much of Langdon's bad luck seems to stem from his choice of second wife. In 1884 he married Mary E. Hoffman, who was 18 years younger and the daughter of Sophronia's best friend. In 1896 Mary, also called Mamie, had a daughter, named Genevieve. In the next 15 years Mary would deliver 12 babies, but only three lived. Two other daughters, Lillian, born in 1889, and Lucille, born in 1897, would survive.

The first report of trouble came in 1899, when Mary was charged with forgery of a check for $25, which equates to $700 today. She managed to get the debt paid. Mary's early family life had been one of prosperity followed by loss. Her father was Dick Hoffman, who ran a bus line in Quincy. Mary's mother bore her namesake daughter at age 16 and by age 34 was a widowed mother of two young children and running a boarding house. Mary Hoffman later remarried a prosperous gentleman named Willard Blakeslee, who also died early, this time leaving her a large estate. His money would allow Mary Blakeslee to rescue her daughter's bad checks on numerous occasions and with increasing frequency. Eventually she would run through the entire estate rescuing her daughter.

In September 1903, Mary was offered a prize job paying $100 per month as secretary to Hattie McCall Travis, who had secured contracts for two concessions at the upcoming 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Travis had been awarded contracts for "the street of Seville and the baby boy incubator." The first featured a Spanish theme and Mary was to run the business affairs in St. Louis while Travis took a trip to secure Spanish dancing girls and other attractions. The second concession was a display of the new-fangled incubators for premature infants complete with babies brought in from St. Louis hospitals, and nurses and doctors giving lectures on the equipment and procedures.

Unfortunately, Travis died in December 1903. Addison Langdon was named executor, and the exhibits came under his charge. By April 1904, the cast of the street of Seville had grown to 100 "singers, dancers, gypsies, mandolin and guitar players and the Spanish orchestra of twenty-five pieces." Spanish food, theater and a marketplace were also offered. But things were falling apart.

In August 1904, the oldest Langdon daughter, Genevieve, married Walter P. Lohman without finishing her studies at the St. Mary's Institute in Quincy. Her younger sister, Lillian, 15, had eloped three weeks before, marrying Edgar Randall, but returned to be in her sister's wedding. The Lohmans then left for California.

That same month, Langdon announced that he was severing ties with his wife, and leaving for Chicago and New York. The Herald reported that "His best friends are of the opinion that the separation should have taken place some time since." Troubles and bad checks continued to pile up for Mary Langdon. Her mother claimed that Mary was insane with a mania for issuing checks and blamed her husband.

Mary soon fled St. Louis and a forgery charge, and followed her husband to Chicago, then joined her newlywed daughter in California. It was there in October 1904 that a St. Louis detective and his wife apprehended her and kept constant guard until they got back to St. Louis, where, for the first time in her long career of forgery, Mary was jailed.

Once in jail, she confessed to everything adding, "Great physical suffering had made me subject to attacks of mental aberration." She explained that she was the reason Blakeslee was now penniless from over 15 years of paying off her daughter's forgeries. At her trial, witnesses specified troubles as far back as 1892, but Blakeslee stood firmly behind her daughter, and Mary spent her time in prison teaching English to a Chinese girl arrested on immigration charges. Eventually, Mary Langdon was released with parole.

In 1906 the lovely Addison house at 16th and Vermont was foreclosed upon, and Mary was living in Los Angeles. There she managed to abscond with $1,140 in money collected from an opera fundraiser for the children's hospital. At the time of the great California earthquake, The Quincy Daily Herald printed the headline, "Mrs. Langdon is in Chicago …Escaped the earthquake with usual luck."

During these years, the youngest daughter, Lucille, grew into a well-paid vaudeville performer, singing and acting with troupes in Chicago and New York. She was known as "The Dresden Doll." But in January 1911, Mary's luck abandoned her. She had accompanied her daughter East on a performance circuit. The two were in Troy, N.Y., when a tragic accident with an alcohol lamp ignited Mary's clothing. Lucille smothered the flames and Mary was taken to a hospital, but the burns proved fatal. Addison Langdon immediately went to be with his 16-year-old-daughter and manage her career. He never returned to Quincy and died quietly in Los Angeles in 1923.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson. She is executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

"Add L. Langdon, Once a Quincy Publisher Dies," Quincy Daily Journal, Dec. 12, 1923.

"Add Langdon and Lucille," Quincy Daily Herald, June 3, 1911.

Add Langdon as Executor," Quincy Daily Herald, Dec. 7, 1903.

"Add Langdon to Resign," Quincy Daily Herald, July 13, 1898.

"Add Langdon's Hard Luck," Quincy Daily Herald, Nov. 14, 1912.

"Addison L. Langdon, Once Well Known Quincyan, Dies at Home in Los Angeles, Quincy Daily Herald, Dec. 11, 1923.

"Circuit Court Transactions," Quincy Daily Herald, May 18, 1906.

"Genevieve is Married," Quincy Daily Herald, Aug. 22, 1904.

"Heirs are Heard From," Quincy Daily Whig, Jan. 19, 1900.

"Lillian Langdon on the Stage," Quincy Daily Herald, Jan. 21, 1899.

"Local News and Gossip," Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 23, 1906.

"Local News Stories Told In Sentences," Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 15, 1904.

"Lucille Now A Real Actress," Quincy Daily Herald, Sept. 8, 1908.

"Mrs. Langdon Dies of Burns," Quincy Daily Journal, Jan. 9, 1911.

"Mrs. Langdon Gets a Plum," Quincy Daily Herald, Sept. 12, 1903.

"Mrs. Langdon in a new Role," Quincy Daily Herald, Nov. 17, 1904.

"Mrs. Langdon is in Chicago," Quincy Daily Herald, April 19, 1906.

"Mrs. Langdon's Life Has Ended," Quincy Daily Journal, Jan. 23, 1904.

"Mrs. Langdon Talks Through Prison Bars," Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 17, 1904.

"Mrs. Langdon Was Indicted," Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 20, 1904.

"Mrs. Langdon Will Be Good," Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 20, 1904.

"Passing of an Old Resident," Quincy Daily Herald, June 24, 1912.

"Quincy Heirs to Untold Wealth," Quincy Daily Whig, Jan. 17, 1900.

"Received Letter from Add Langdon," Quincy Daily Herald, Sept. 27, 1917.

"Round the Town," Quincy Daily Journal, Dec. 12, 1923.

"Skips Out With Hospital Money," Quincy Daily Journal, March 15, 1906.

"Testimony in Langdon Case," Quincy Daily Whig, Nov. 17, 1904.

"The Langdon Sisters," Quincy Daily Herald, Feb. 6, 1899.

"The Langdon's Have Parted," Quincy Daily Herald, Aug. 16, 1904.

"The Seville on the Pike," Quincy Daily Herald, April 27, 1904.

"Wifey Caught her in an Auto," Quincy Daily Herald, April 30, 1915.

"With Forgery," Quincy Daily Journal, Aug. 5, 1899.