Allan Nevins and the Gateway to History

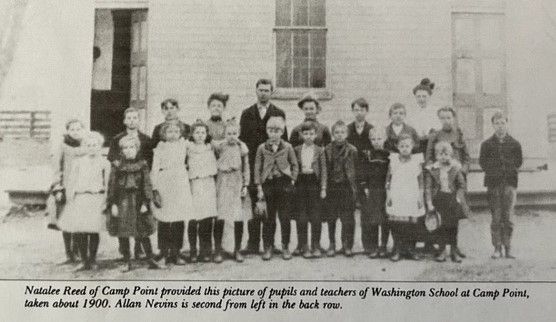

Pupils and teachers at Washington school in Camp Point. Allan Nevins is second from the left in the back row. (Courtesy of Illinois Historical Journal, 1988)

Allan Nevins’s memories of growing up on an Adams County farm near Camp Point in the 1890’s and first decade of the twentieth century were not idyllic. His parents’ generation, which he wrote about in an unpublished manuscript owned by Columbia University and quoted in Fetner, faced a changing society which “infringed on their ‘old status,” making them “feel dependent [and] helpless in the grip of forces that nobody…understood.” The “local merchants…made unconscionable profits on farm implements, clothing, and everything else from sealing wax to coffins; that is if they could….”

In 1971, Albin Krebs of The New York Times wrote in a front—page obituary, “Mr. Nevins, known as phenomenally tireless worker, was fond of saying that he didn't really think he had worked hard since he left his father's stock and grain farm to go to college.” Krebs added that Nevins’s parents had a library of 500 books in the house. Nevins’s younger colleague, the historian Robert Middlekauff, wrote that “at six years of age,” Nevins “was harnessing the horse to the buggy and driving it to the fields with water for the men. At eight years he could manage a team and not long afterwards he was driving a cultivator, pulled by horses up and down ‘endless’ rows of corn.”

Nevins had spoken decades after he became a prominent historian, teaching thirty years at Columbia University and other institutions and twice winning the Pulitzer Prize for biography. The New York Times described him as “a prolific writer who brought to his work an engaging style, a profound sense of fairness, a deep humanism and a total respect for the truth.”

Nevins’s own biographer, Gerald L. Fetner, called him “a nineteenth century man living out his life in the twentieth century.” Writing in 2004, Fetner said Nevins “saw history as an agency for tempering public controversy”, a characterization in striking contrast to our nation’s present controversies over the content and emphases in teaching United States history. Apart from his writing, Nevins broadened historical scholarship by three achievements: establishing the Columbia Oral History Project, founding American Heritage magazine, and teaching the “Gateway to History” course at Columbia, topics discussed later in this series.

Throughout his life Nevins remained close to his Adams County relatives as the Quincy Herald Whig followed his career. When he was named, the Harmsworth Visiting Professor of American History at Queens College in Oxford University, the Herald Whig, on January 7, 1941, wrote that he “comes annually to visit relatives, including his sister, Mrs. Lewis Omer of Carthage and aunt, Miss Emma Stahl of Camp Point.” The story described the Harmsworth professorship as “one of the most distinguished posts in American scholarship…endowed to encourage the study of American history in England.”

Nevins had not planned to be an historian—at least not immediately-- after graduating from the University of Illinois with a master’s degree in English in 1913. He worked as an editorial writer for The New York Evening Post, then became literary editor of The Sun, a New York tabloid, and finally became an editorial writer for The World, first established in New York as Joseph Pulitzer’s broadsheet. In 1916 he met Mary Fleming Richardson at a party, and they married that year at her parents’ home on Long Island.

Throughout his journalism career, though, Nevins also wrote about American history. Two books, The American States During and After the Revolution in 1924, and The Emergence of Modern America in 1927, brought him to the Columbia history faculty in 1928, where he remained for three decades before retiring and continuing his scholarship at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.

His first Pulitzer—which secured his international reputation—was for Grover Cleveland: a Study in Courage in 1933. The historian Eric F. Goldman has written that Cleveland’s presidency (1885—1889, then a second term 1893—1897), “marked a high point in the transition from an agrarian, small-town America to an industrialized, urbanized society, and the transition left millions sure that America as the land of wide-open freedom and opportunity was more in danger than it had ever been before.”

Perhaps Nevins’s interest in Cleveland, in part, reflected his experience on his parents’ Adams County farm, observing the community’s helplessness “in the grip of forces that nobody…understood.” Nevins criticized Cleveland’s use of federal troops to end the Pullman railroad strike in 1894—an event for which the emerging labor union leader, Eugene V. Debs, was jailed for contempt of court—but praised Cleveland’s insistence that United States currency remain on the gold standard. Cleveland’s policy against monetizing silver resisted inflation but divided the Democratic Party over economic policy until 1933, when Franklin D. Roosevelt ended the gold standard and Congress authorized both silver and gold as precious metals to support the currency.

Nevins’s second Pulitzer, in 1937, for Hamilton Fish: The Inner Workings of the Grant Administration, considered the American aristocrat who became Secretary of State in a troubled administration led by a president whose associates betrayed him. The Times said Nevins had “flooded with light the dark corners of the Grant administration and made possible a far more accurate and just estimate of political events in those unhappy years.”

Nevins remained active in journalism and public affairs after his Columbia appointment, continuing to write on international issues for such publications as Current History. In 1960 he helped draft Senator John F. Kennedy’s speech accepting the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, and earlier that year had returned to Illinois to support Senator Paul H. Douglas’s reelection. That Nevins family tradition continues today with his granddaughter, the journalist Jane Mayer, author of Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right, who appears frequently as a commentator on public broadcasting programs.

Sources

“Allan Nevins. Noted Historian, Goes to England.” Quincy Herald Whig, January 7, 1941,

p. 9.

Ankrom, Reg. “Pulitzer Prize-winning Historian Disappoints QU Friar.” Quincy Herald

Whig, March 4, 2018, p.7.

“Cleveland Symbol of Courage.” The New York Times Book Review, October 16, 1932,

Section T, p. 1.

Fetner, Gerald L. Immersed in Great Affairs: Allan Nevins and the Heroic Age of

American History. New York: SUNY Press, 2004, pp. 9, 13.

Goldman, Eric F. “The Presidency as Moral Leadership.” 280 Annals of the American

Academy of Policy and Social Sciences (1952), pp. 37, 40.

Jumonville, Neil. Henry Steele Commager: Midcentury Liberalism and the History of the

Present. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Krebs, Albin. “Allan Nevins, Historian, Dies; Winner of Two Pulitzer Prizes.” The New

York Times, March 6, 1971, p. 1.

Middlekauff, Robert, “Telling the Story of the Civil War: Allan Nevins as a Narrative

Historian,” The Huntington Quarterly 56 (Winter 1993), p. 68.