Ancestor meets 50th Illinois at Fort Donelson

The Union victory at the Battle of Fort Donelson after five days of fighting, Feb. 11-16, 1862, made Ulysses S. Grant a major general, cleared a path for invasion into the South and brought together young men of the 50th Illinois Infantry, formed in Quincy, with my great-grandfather, Isaac Cook of Kentucky.

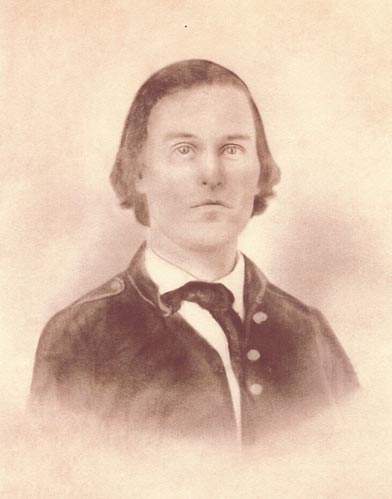

Cook, 20, had enrolled in the Union Army on Oct. 15, 1861, at Henderson, Ky. He and his two brothers — William, 21, and James, 19 — joined Company A, 25th Regiment, Kentucky Volunteer Infantry. Isaac was wounded at Fort Donelson. William and James were killed there.

Fort Donelson was the North’s first major victory of the Civil War. The capture of the fort on the Cumberland River opened the way into the very heart of the Confederacy. Gen. Grant, after leading his green recruits through Quincy in April 1861 and on to battle in Missouri later that year, moved south, crossing the Ohio River at Paducah. Grant moved up the Tennessee River to attack Fort Henry, which surrendered to his forces, including the 50th Illinois, on Feb. 6, 1862. He then moved 12 miles overland to attack Fort Donelson. Grant’s strategy was to use U.S. Navy ironclad gunboats to pound the forts into submission. That worked well at Fort Henry, but the gunboats were forced to withdraw after sustaining heavy damage from Fort Donelson’s river batteries, including some guns on the crown of a 100-foot bluff.

Grant’s forces surrounded the Confederates at Donelson, but on the morning of Feb. 15, Confederate Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, Fort Donelson’s second in command, attempted to break out, launching a dawn assault on the unprotected right flank of the Union line.

Isaac Cook and his brothers were believed among the Union fighters there. After two hours of heavy fighting, Pillow’s men, including Lt. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest, were able to push the Union troops out of the way to open an escape route. But the Confederates, unexpectedly, were ordered to return to their entrenchments, a result of confusion and indecision among the Confederate commanders. Grant ordered a counter-attack, and the Union forces were poised to seize Fort Donelson and its river batteries on Feb. 16.

The men of the Adams county formed 50th Illinois, who had described the sound of rebel bullets hitting their bayonets the night before “like so much hail,” waited in silence, breathing deeply, early that Sunday morning for the order to attack the fort from their position in a ravine to the west. It did not come. Instead, at 10 a.m., the rebels struck their colors and surrendered.

Confederate Generals John B. Floyd and Pillow had turned over command to Confederate Gen. Simon B. Buckner, who agreed to remain behind and surrender the army. That was something Confederate Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest would refuse to do. He angrily stormed out with his 700 men.

The Confederates had been evacuating Bowling Green, Ky., at the time and wanted Fort Donelson to protect the flank of their retreat through Nashville. Now, with the capture of Fort Donelson, that strategy died. Grant’s success resulted in his rank of major general, and the terms he demanded of his West Point classmate, friend and now Confederate Gen. Buckner earned him the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

After being wounded at Fort Donelson, Isaac Cook was sent to a hospital in Henderson, Ky. As a result he missed the Battle of Shiloh, April 6-7. That was a good battle to miss. When it joined the battle at mid-morning on that first day, the 50th suffered 79 casualties within 15 minutes. The unit’s commanding officer, Col. Moses Bane of Payson, lost his right arm to a rebel’s musket ball in the first minute.

Because it suffered so many casualties, the 25th Kentucky Infantry ceased to exist on April 13, 1862, and its members were consolidated with the 17th Kentucky Infantry. My brother, John Cook, is very good at genealogy and requested the National Archives to search for any of my great-grandfather’s records.

That’s when he found out about the court-martial.

After Isaac Cook left the hospital, he was sent home to Hopkinsville, Ky., to recover. He failed to rejoin his unit. As a Marine Corps lawyer, a judge advocate, assigned to the First Marine Air Wing, in DaNang, Vietnam, it was interesting for me to read the record of my great grandfather’s court-martial. The proceedings haven’t changed much in a hundred years. The language is still the same. Isaac Cook faced: Charge Desertion Specification — in that he the Said Isaac A. Cook a private of Co. G 17 Regt Ky Vol Inft being duly enlisted in the Service of the United States did Desert his Co and Regt at Hopkinsville Ky on or about the 3rd Day of December 1862 and Remained absent therefrom until the 24th day of September 1863 when He was Brought to his Regt under guard then encamped near Chattanooga Tenn.

A general court-martial was conducted Oct. 22, 1863, and Cook was sentenced to forfeit his pay of $13 per month for 14 months and placed on hard labor for 30 days. The sentence was signed by the judge advocate. The lengthy written record of the court-martial, taken in a war zone, is impressive — 11 handwritten legal-size pages.

Cook returned to the 17th Kentucky Infantry Regiment, which served under Sherman on the March from Chattanooga to Atlanta. Cook was wounded once again, either at Allatoona or Resaca, on May 23, 1864. This time he returned to duty pretty quickly.

The 17th Regiment mustered out of the service at Louisville, Ky., on Jan. 23, 1865, and Cook received an honorable discharge. As a result of his conviction, he received one month’s pay for most of his service during the Civil War. He did receive a pension, however, as did his wife after he died.

The names “William” and “James” are common in our family; not so “Isaac.” My brother tells me Isaac was born in McMinn County, Tenn., and there was a famous abolitionist near there, Isaac Anderson, a Presbyterian Minister and the founder of Maryville College. And Isaac Cook’s full name, indeed, was “Isaac Anderson Cook.” My brother also found out that Isaac had an aunt, Lucinda Cook, who married a man with the last name “Daniel.” They had a son named Jack. Jack founded a whiskey distillery. That’s another story.

We sometimes complain about things, but our lives for the most part have been so much better than the lives of those who went before us. The Civil War was a terrible time. Sherman said “War is Hell,” and my great-grandfather knew it.

Robert Cook, a longtime resident of Quincy, is a judge on the Illinois Appellate Court in Springfield. He is a member of the Board of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

Costigan, David. "Once Upon a Time: Grant Comes to Quincy and Northeast Missouri," Quincy Herald-Whig, September 25, 2011. At http://www.adamscohistory.org/Grant__Ulysses_S..pdf

Hubert, Charles F. History of the Fiftieth Regiment, Illinois Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Union. Kansas City: Western Veteran Publishing Company, 1894.