Anti-slavery preacher set adrift on raft by angry mob

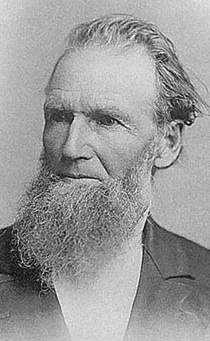

Pardee Butler was born in New York state and raised in Ohio two centuries ago. Becoming a man of steadfast conviction, he helped the growing United States stay free of slavery. His young adulthood in Ohio was spent herding sheep, teaching school and memorizing the New Testament. He married Sybil Carleton in 1843. He also knew Judge Brown, the most influential man in his neighborhood and an uncle to John Brown, the man who raided the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, W.Va., in 1859 in a violent attempt to end slavery.

A fierce desire to preach in the expanding United States pushed him westward. He moved his family to southern Iowa and then spent three years preaching in the Military Tract of Illinois, over 100 miles from home, mostly in Brown, Schuyler and eastern Adams counties. He revived churches in Mount Sterling, Rushville, Ripley and other towns. Those churches were ringing with Butler's energetic voice, and he considered his days preaching here as the "golden days of his life."

"There has been no field in which my labor as an evangelist has yielded a richer harvest," Butler later wrote about his days in this region. He wanted to buy land somewhere in West-Central Illinois, but prices were higher by 1855, and most Military Tract land had been purchased.

In 1855 Butler left his family at his Uncle Gorham's farm near Canton, Ill., and on horseback set out for Kansas Territory to investigate land. Kansas was approaching statehood, and land was cheap and tillable. His plans to live in Mount Sterling, Ill., for a few years to save money for their future Kansas farm were changed when he realized how close slavery was to claiming that territory.

Butler's declarations to vote the Free-Soil ticket did not concern people in Ohio and Illinois, but he would soon find out the severity of the Kansas Territory question, coming face-to-face with pro-slavery forces flocking there. The political viewpoints of whether Kansas would be a slave state or free state dominated life on the Kansas/Missouri border.

Butler crossed the Mississippi River at Quincy and 10 days later he was threatened by slaveholders in Chillicothe, Mo., for mentioning free-state politics. He pressed on and staked a claim near Stranger Creek, 12 miles from Atchison, Kan. He returned to Illinois immediately to gather his family.

The Missouri River steamer trip he had planned from Atchison to St. Louis was delayed, so Butler stayed at a boarding house for the night. He had made it known to several locals that he intended to vote for Kansas as a free state, and a meeting of pro-slavery men was held about what they should do with Butler. They tried to force him to sign a paper of "pro-slavery resolutions," but he refused.

The mob was so incensed that many wanted to hang him, but it was decided to set him off on the Missouri river on a crude two-logged raft. They hung a flag from a wooden log that had a sketch of Butler riding a horse with a female behind him. The flag ended with the words, "Rev' Mr. Butler, agent for the underground railroad."

The flag accused him of being a reporter for Horace Greeley's New York Tribune, an agent for the Emigrant Aid Society that sent free-state voters to Kansas Territory, and a "thief" of human property for helping fugitive slaves. All of these offenses they likely thought would get him in grave trouble as he traveled down the Missouri River.

Butler always maintained that he told people he planned to vote for Kansas as a free state, calmly and plainly.

Butler floated down the river a few miles, then used the crude flagpole to make it to shore. He eventually boarded the steamer Pole Star and made it back to Illinois to retrieve his family despite threats to his life.

Butler and his family visited the churches where he had preached. He then borrowed a spring wagon from Camp Point town founder Peter Garrett and took his family to Kansas.

In October 1856, Butler was back in West-Central Illinois to spread the truth about treatment of "Free-Soilers" in Kansas Territory. Col. Thomas Brockman of Mount Sterling joined him in villages in Hancock, McDonough, Brown and Adams counties to speak about the "present crisis of the country." From Oct. 14-30, 1856, they spoke in Macomb, Blandinsville, Warsaw, Hamilton, Augusta, Plymouth, Camp Point, Mendon, Ursa, Chili, Lima, Liberty, Payson, Burton and Quincy. Public advertisements in The Quincy Whig declared Butler a victim of "Border Ruffianism": "Those who wish to hear the truth and facts as to the occurrences in Kansas will do well to attend."

Some of these villages had strong anti-slavery ties. In Plymouth during the mid-1840s, students of Dr. David Nelson's Mission Institute in Quincy, Elias Kirkland and George Thompson, began the Congregational Church there. Both students and other Plymouth residents participated in illegal Underground Railroad runs to Canada. Augusta, Macomb, Payson and especially Mendon also had strong anti-slavery roots 20 years before Butler preached there.

Thomas Killiam of Lima, Ill., wrote to The Quincy Daily Whig about Butler and Brockman's 1856 Lima speech. His letter to the editor remains the only known newspaper account of the event. Killiam called it a "Free Meeting," and deemed it a success. He wrote, "Tho all parties are aroused, most of the thinking and respectable part of the community have taken a bold and decided stand against the Douglas Democracy."

He wrote that the Democrats at the meeting who would vote for a free Kansas "cannot sanction the conduct of their party any longer."

Pardee Butler was back in Camp Point during the Christmas season of 1858. He preached and attacked the institution of slavery. When he returned to Kansas he continued speaking against slavery, organizing the Republican Party and working with the Disciples of Christ denomination. Butler died in 1888.

Heather Bangert is involved with several local history projects. She is a member of Friends of the Log Cabins, has given tours at Woodland Cemetery and John Wood Mansion, and is an archaeological field/lab technician.

Sources:

Butler, Pardee, and Hastings, Rosetta B. "Personal Recollections of Pardee Butler," Standard Publishing Co., 1889.

"Butler and Brockman in Lima" Quincy Daily Whig, Nov. 2, 1856.

Cobb, Bradley. "Pardee Butler: The Definitive Collection," Cobb Publishing, Oklahoma, 2014.

"Fifty Years in Kansas" St. Louis Christian Evangelist, May 20, 1909.

Johnson, Daniel T., "Pardee Butler: Kansas Abolitionist," Master of Arts Thesis, Kansas State University, 1962.

"Public Meeting at Camp Point." Quincy Daily Whig, June 14, 1856.

"Public Speaking." Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 14, 1856.

"Public Speaking." Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 16, 1856.

"Public Speaking." Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 17, 1856.

"Public Speaking." Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 18, 1856.

"Public Speaking." Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 25, 1856.