Anti-Smoking Movement in Quincy Waxed and Waned

A few months before the American Civil War began; J. B. Harris of Quincy offered free seeds and advice to any Adams County resident wanting to grow tobacco. The military had long considered its use essential for fighting men, and Union generals from Grant to Sherman frequently smoked cigars and touted their benefits. During the war’s first year, the county raised 50,000 pounds of tobacco and its cultivation spread widely after the war ended.

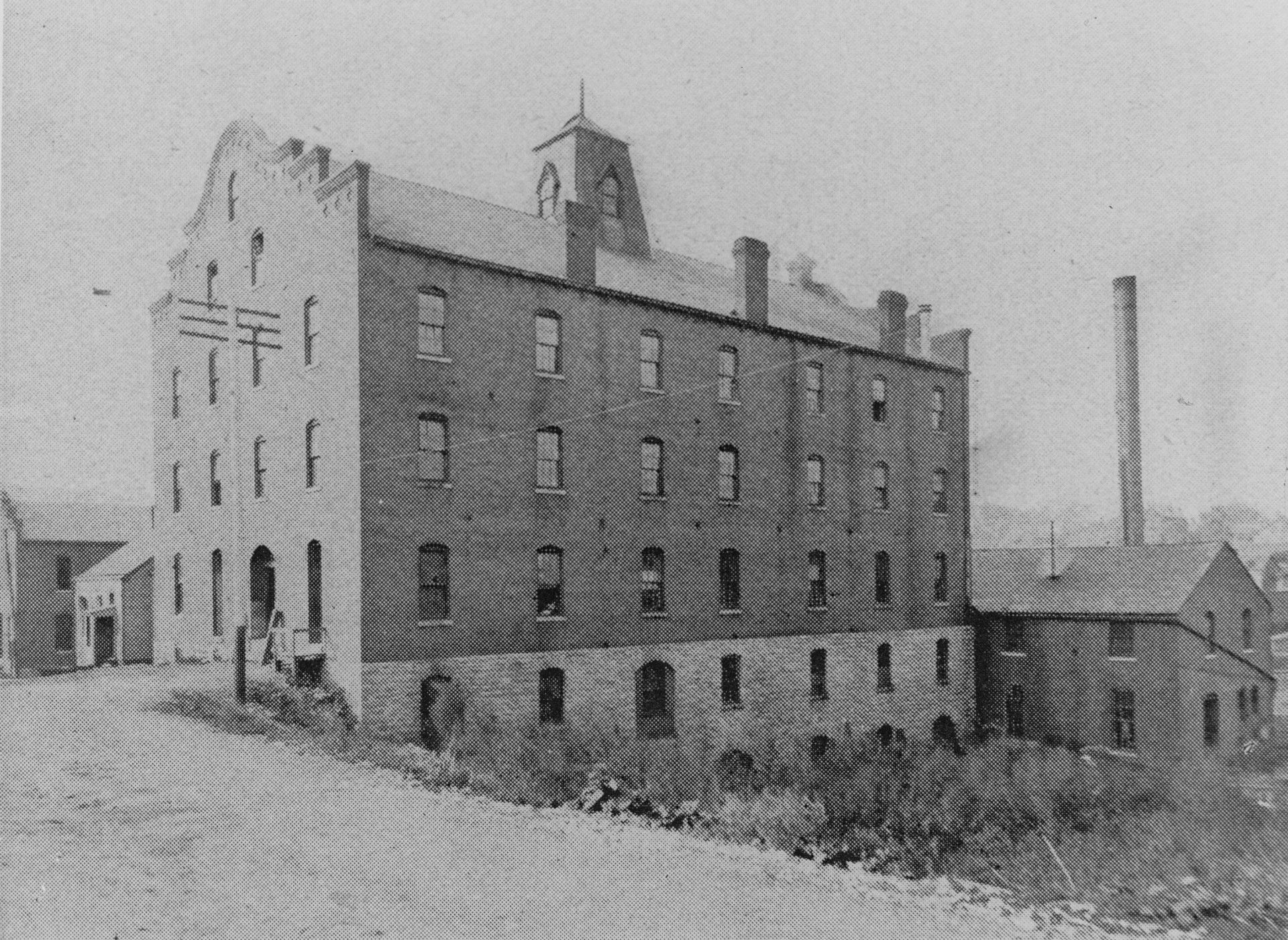

By 1879, Adams County had become a major tobacco producer and processor with five factories employing a total of about 1,200 people. Tobacco emerged as Quincy’s largest industry. Tobacco yielded so much local income that the federal government established an Internal Revenue District here, one of only four in the nation.

Tobacco use became common throughout local society. As a way for children to help support their families, particularly those who had lost a father in the War, Quincy Public Schools gave them the option of working in tobacco factories rather than attending classes. Foremen allowed boys, but not girls, to chew tobacco or smoke during their seven-to-ten hours of daily labor. Political, fraternal and church meetings regularly held “smokers” and private homes and public buildings from the courthouse to the library had spittoons.

Citizens widely viewed smoking as masculine, social, and not only invigorating but healthy. While some people questioned this last assertion, a May, 1906 Quincy Daily Whig article underscored this belief. “Nicotine is a strong disinfectant...and smokers enjoy immunity from certain illnesses, and the presence of a powerful antiseptic.”

Even as growing medical evidence gave credence to possible ill-effects of smoking, pharmacies continued to sell most available tobacco products. Christie Drug Store at 501 Hampshire introduced “Chico” cigars to all local men “who appreciate a good smoke.” The pharmacist at the store, Edward Granacher, even wagered that no Quincy man could smoke even one Chico until he fully consumed it before taking it from his lips. At the same time, pharmacies across the city offered remedies for those wanting to end their nicotine addiction, such as “Nicotol” and “Nix-O-Tine Tobacco Remedy”—later marketed as the popular drink mix “Kool-Aid”.

An anti-smoking lobby emerged in the late 19th century and aligned itself with the growing prohibition movement against alcohol. Soon proponents outlined Constitutional Amendments banning both alcohol and tobacco. Illinois native Lucy Page Gaston became the leader of this anti-smoking movement, proclaiming that this vice—especially the new practice of rolling tobacco into “cigarettes” or, as users colloquially called them, “filled blankets”—produced as much social evil as drinking.

Gaston founded the Chicago Anti-Cigarette League of America in 1899, the first of its kind in the United States; it soon spread nationwide and in a few years numbered 300,000 members. In July 1902, Gaston came to Quincy and established a local chapter.

Later that year she met with the city’s Mayor John A. Steinbach and Police Chief William Hild and launched an anti-smoking crusade in Quincy. After their meeting, Mayor Steinbach publicly promised he would never smoke another cigarette. While many observers dismissed this statement as a political ploy, anti-smoking sentiment reached a zenith in April 1907 when the Illinois legislature banned the manufacturing and sale of cigarettes, cigars, and paper used to make them.

Local papers reacted swiftly and scathingly. An editorial in the Quincy Daily Herald stated: “The legislature didn’t know what it was doing...and was the victim of a huge joke and Miss Lucy Page Gaston celebrates today.” The editorial concluded, “Gaston made her argument in a room filled with cigarette smoke.” This law stayed in effect for nearly a year before the Illinois Supreme Court overruled it on a technicality that only cigarettes with substances harmful to health can be banned, not “pure tobacco.”

The anti-smoking crusade, though, gained momentum in May 1915 when Quincy High School principal Zens L. Smith banned tobacco use by students during and after school and encouraged police to enforce the misdemeanor charge for underage smoking. The Quincy Police Department itself banned smoking by on-duty patrolmen until after midnight and some local organizations partitioned smoking rooms.

J.G. Forsthove, traffic superintendent of the Quincy Streetcar Railway Company, prohibited smoking in closed cars and some churches admonished children (but not adult males) for this “filthy habit.” Quincy student Leonard Stegeman won first prize in a statewide contest about the harmful effects of “coffin nails.”

This controversy escalated when women, eager for suffrage and other legal rights, began smoking in public. Businesses, organizations and churches that had endorsed the rights of men to smoke deemed it scandalous for Quincy women to light up. Representative James C. McGloon introduced a bill in the Illinois House in February 1917 to prohibit women from smoking cigarettes in public. Local government officials heartily supported it.

The American entry into World War I in April 1917, though, and the concurrent world-wide influenza epidemic hindered the anti-smoking movement. When reporters asked General John J, Pershing what he needed to win the war, he famously responded “tobacco as much as bullets.” The local YMCA reversed its anti-smoking policy and began shipping cigarettes to troops. Organizations from the Masons to the Chamber of Commerce also began including cigarettes in their care packages. When the public saw boys smoking as they went to war, this image aligned with patriotism for the Allied cause.

Many people—including some health officials—also believed that smoking helped stave off the influenza that had already killed millions and insidiously targeted the young most of all. Officials at Camp Parker, where many Quincyans trained for war, told recruits to “smoke up.” In response, local support drives collected 600 pounds of “joy weed” for their fortification against the flu during the long train ride to Camp Logan, Texas, and deployment overseas.

Sources

Brandt, Allan M. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined

America. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

“Camp Parker Boys Told to ‘Smoke Up.’” Quincy Daily Herald, Aug. 18, 1917, 12.

The History of Adams County, Illinois: Containing a History of the County—Its Cities, Towns, Etc. Chicago: Murray, Williamson & Phelps, 1879, 453-8.

“Local Brevities.” Quincy Daily Herald, July, 15, 1902, 8.

“Peace to Cigarette’s Ashes.” Quincy Daily Herald, June 26, 1907, 4.

“Smoking a Cigar.” Quincy Daily Journal, March 28, 1906, 6.

“Tobacco as a Disinfectant.” Quincy Daily Whig, May 20, 1906, 9.

Whelan, Elizabeth M. A Smoking Gun: How the Tobacco Industry Gets Away With Murder. Philadelphia, PA.: George F. Stickley Co., 1984.