Asbury for president; Van Buren for magistrate

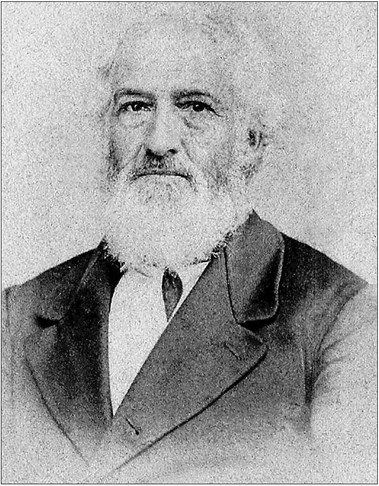

In his 1882 memoir, expansively entitled “Reminiscences of Quincy, Illinois,” containing historical events, anecdotes, matters concerning old settlers and old times, Henry Asbury recounted what it was like for a young man to travel by horseback from his birthplace in Kentucky to settle in Quincy in 1834.

After crossing the Ohio River into Indiana, then into Illinois, he reported that he and his friend crossed prairie all day without seeing another person or dwelling, then spent the night at the only farm for miles in any direction. Another long day’s ride brought them to Springfield, but they were not impressed: “It was a rather hard place, however, and not up to its reputation … and was then, as it is now, the muddiest town in the world.”

Jacksonville, however, met with approval — it was larger than Springfield and Chicago. With a few more days of riding, he reached his destination, Quincy, and his friend continued west.

Shortly after establishing residence in a log cabin at Seventh and Hampshire, Asbury began his studies with the noted Orville H. Browning and became a lawyer in 1837. His first law partnership was with Abraham Jonas, a friend of another young Illinois attorney and friend of Browning, Abraham Lincoln. Jonas introduced them.

Asbury’s connection to Lincoln led to numerous behind-the-scenes interactions with and for the future president, some of national significance. He is credited with writing the pivotal four questions Lincoln posed to Douglas in the second of the debates during their campaign for the Senate. The seemingly innocent first question asked for Douglas’s opinion on allowing Kansas statehood on the basis of its submitting the request and writing a Constitution, even if it fell short of the required population; but the successive questions built on the underlying principles of that one, and deftly backed Douglas into a corner on the extension of slavery.

Lincoln well understood the significance. When other Republican leaders tried to dissuade him from asking the questions, they reportedly warned him, “If you do you can never be senator,” to which Lincoln replied, “Gentlemen, I am killing larger game; if Douglas answers, he can never be president, and the battle of 1860 (for the presidency) is worth a hundred of this.” Lincoln and Asbury were right, but there was more work to be done before 1860. Asbury became one of the founding leaders of the Republican Party in Illinois.

Long before his significance in state and national politics, however, Asbury had established himself as a leader in Quincy. Just months after his arrival, Asbury attended a meeting at the home of Dr. Joseph Ralston on Maine Street at which a petition was written to the Masonic Grand Lodge of Kentucky requesting permission for a charter for the Bodley Lodge No. 1 to be formed in Quincy. The charter was granted, and at 24, young Asbury was first to hold the office of “tyler.”

He was elected justice of the peace in 1836, but there was much more to that election story than just the win.

When national, state, and local elections took place in 1836, political parties were still fluid and developing, and candidates’ support was often gained through their stand on specific issues and their own personalities and friendships.

The first Quincy city charter’s voting qualifications were still in effect: a voter need only be a white man over 21 years old who had lived in the state for at least six months prior to any election. He did not have to be a citizen or even speak English.

Elections were held “viva voce,” which was interpreted to mean “sing out your choice.” Voters showed up at a polling place and responded aloud to questions about whom they wished to vote, which the clerks of the election then recorded.

In 1836, Asbury and his opponent in the election for justice of the peace had both been Whigs until the other man’s defection to the Democrats just before the election. Asbury also had friends who were Democrats, and although they supported their party’s Presidential candidate, Martin Van Buren, they supported Henry for justice of the peace.

Asbury confessed that he was utterly naïve about politics, and just did whatever his more savvy supporters told him to do. His friends, intent on getting him elected, urged him to go to two particular grocery stores a few days before the election and offer to buy drinks for the grocers and their friends who would stop by after the election. The grocers would keep a tab, and Henry would pay up later. Both agreed.

Henry and his friends had become acquainted with new arrivals from Germany who had been in the city for more than six months, and were aware of the election, but did not speak English yet. Asbury’s English-speaking supporters carefully schooled the German men to go to the polls and reply “Asbury” when the election official asked for whom they wished to vote.

In Asbury’s words: “ … (H)aving been impressed by my friends to vote for Asbury — they had retained my name only — and after giving their names to the clerks of the election when they came up to vote, were asked by the judges, “Who do you vote for?” to which they promptly replied, “For Asbury.” “Who do you vote for for President?” to which they promptly replied, “For Asbury;” then “Who do you vote for for magistrate?” That was a stumper, but after a little they said, “For Van Buren.”

When Asbury heard of what was happening, he went to the election judges and explained that the German men were simply trying to vote for him as justice of the peace. In his memoir, he wryly noted, “The judges agreed to explain to the next voters, but the first votes recorded for Asbury for President and Van Buren for justice of the peace, were lost to both.”

Asbury lost his votes for the presidency, but won election as justice of the peace by 30 votes. After the polls closed and the result had been announced, the jubilant young man started home. He was hailed by a group of men celebrating at one of the groceries where he had agreed to treat, so he offered to pay for a round of beer for everyone on his prearranged tab. When one of the German men asked for some Rhine beer, instead of the local brew, Asbury told the bar keeper to give him what he wanted, and went on home. He had $15 in his pocket, and felt he could certainly afford that.

Henry went to the grocer the next day to settle up, and learned that on the previous evening, his friends had interpreted “Give him what he wants” to apply to every man there, and his friends had partied all night, “singing and shouting for Asbury and Van Buren.” They had drunk all 30 bottles of the bar keeper’s Rhine wine at one dollar a bottle, and the bill was $42.

Henry had to borrow to pay his tab, and asserted, “This was the first and last time I treated at an election, and now I don’t believe it gained me a single vote. In Quincy, in 1836, the sum of even forty-two dollars was a large amount to a young greenhorn fellow without any money.” But young Henry Asbury had won an election.

Linda Riggs Mayfield is a researcher, writer, and online consultant for doctoral scholars and authors. She retired from the associate faculty of Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing, and serves on the board of the Historical Society.