Black officer found haven in Quincy, only to fall

The first Quincy police patrol was created in 1839. Since then, five officers have died in the line of duty. One of them was William H. Dallas. He was the first black police officer to lose his life in Quincy and the first in Illinois. His story is both tragic and heroic, as he showed that through hard work and dedication, he could achieve success. But tragically, his life was cut short by a criminal's bullet.

Dallas was born into a slave family in 1844, probably in South Carolina. He managed to escape and fled, first to Chicago and then to Quincy. He had heard of the good efforts of the community and particularly those by J.K. Van Doorn, which made Quincy a safe haven for escaped slaves. However, concerned about the Fugitive Slave Act, Dallas left for Canada. Only four months after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, he enlisted with the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.

On his enlistment form he listed his place of birth as Adams County, Ill., and gave his occupation as a "Farmer." According to the form, he was 5 feet, 9 inches tall with hazel eyes and a light complexion. He was wounded when taking part in the fighting on James Island in South Carolina in July 1864, suffering an injury to his right scapula and shoulder joint. After being wounded, he spent the next year recuperating and was in a hospital in Worcester, Mass., before being medically discharged from the Army due to muscle atrophy on Sept. 22, 1865. After the war, Dallas returned to Quincy.

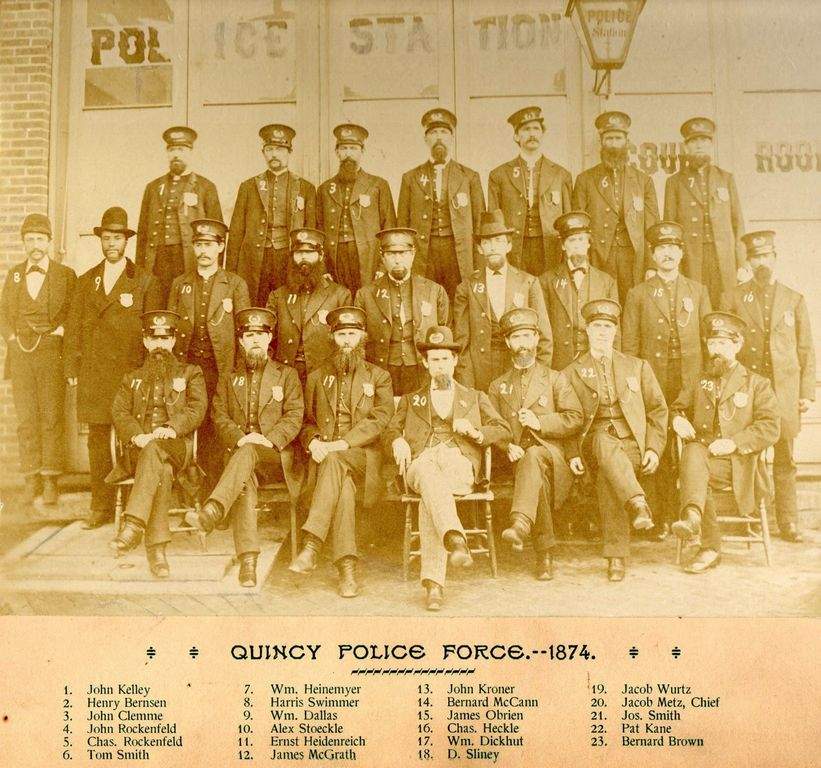

On Oct. 15, 1868, he married Virginia "Jennie" Winn, and the couple had two sons, George and William Junior. He became a Quincy police officer in 1874. He was known as "Billy" and was, according to the Quincy Whig, "one of the best officers on the force." On May 29, 1876, Dallas and a fellow officer, James O'Brien, were on the city's north side, where over the past several weeks a number of burglaries had occurred. The thieves had been operating late at night, plundering farms and absconding with everything from chickens to wood. The police department on that Monday night had received a tip that aided their quest.

Nathaniel Pease of Eighth and Sycamore (the present home of Washington Elementary School) entered his barn and noticed a stash of stolen goods. He immediately notified the police. Officers Dallas and O'Brien were dispatched to the scene. They staked out the barn that night and at 2 a.m. heard noises. Four men had entered the building, but before the miscreants could get their hands on the stolen items, the officers shouted at them to halt. Instead, the intruders began shooting and Dallas and O'Brien returned fire, but, as far as they could tell, no bullets hit the mark.

Dallas and his partner were unaware that one of the four burglars had gone under the barn -- the structure was raised several feet -- until he fired three shots. One struck Dallas in the chin. The wounded officer was then hit by bullets from the other robbers, and he fell to the ground. Thinking that Dallas had died from his wounds, O'Brien began chasing the burglars.

Dallas, though severely wounded, had enough strength left to crawl to the Pease home, where help was summoned. Dallas was taken to his home and underwent surgery, though without success. He was declared dead at 10 a.m. May 30, 1876.

The shooting death shocked the community. In the wake of Dallas' murder, a collection was raised to pay the mortgage for the home Dallas and his pregnant wife had recently purchased. His funeral was Thursday, June 1, at the African Methodist Episcopal Church on the corner of Ninth and Oak. The Quincy Whig noted that "the edifice was crowded by those who had assembled to pay the last sad tribute of respect to the memory of the gallant officer." According to the Whig, "The police force entire attended the burial. A long line of carriages followed the remains to the cemetery, containing citizens who manifested the grief which prevails throughout the community over the sad event."

After the murder, the police launched a massive investigation to track down the culprits. However, it was to no avail. Several arrests were made, but it was ascertained that those arrested were not party to the murder of Dallas. His murder remains unsolved.

William H. Dallas lived an extraordinary life. Born into slavery, he escaped, fought for the Union, and rose to become an officer of the law during a time when racial prejudice was the norm. His time in Quincy, therefore, is instructive. Quincy has always had a reputation as a welcoming and friendly community, and Dallas' time in the Gem City shows that to be the case. Before emancipation, Dallas came to Quincy because it was a place of refuge for runaway slaves. In the 1870s, though blacks were free but by no means equal, Dallas service as a police officer is another testament to the city's progressive views on race.

Dallas younger son, William H. Dallas, was born after his father died. He grew up in Quincy. After the president's call for volunteers for the 1898 Spanish-American War, William enlisted as a private in Company I of the Eighth Illinois National Guard. The governor had created "the Eighth Illinois National Guards, composed entirely, from colonel to private, of colored men, of the state of Illinois. The Eighth became the only colored regiment in our history commended entirely by Afro-Americans."

William's captain was Frederick Ball. William "received more promotions than any man in the regiment, he receiving two commissions in less than two months." No doubt his father would have been proud.

Justin Coffey is an associate professor of history at Quincy University with a doctorate from the University of Illinois. He is a former president of the Historical Society and is chief political analyst for WGEM.

Editor's note: A shorter version of this article was published in 2013. New research was done and additional information was included. The Society thought the topic was important enough to produce a revised article because of the marker dedication Feb. 7 in Woodland Cemetery.

Sources:

"City's first fallen officer was a black man and Civil War hero," Quincy Herald Whig, July 29, 1999, Page 12A.

"Dallas," Quincy Whig, June 8, 1876.

Goode, W.T., The "Eighth Illinois." Chicago: Blakely Printing, 1899.

"Startling Tragedy," Quincy Whig, June 1, 1876.