Black physician who served in WWI was mover, shaker

Dr. Hosea J. Nichols was one of the 104 doctors of African-American descent who were physicians in World War I.

His father, William Nichols, who had been born a slave, served with the Union Army in the 59th U.S. Colored Infantry during the Civil War. Hosea was born in 1870. He and his six siblings were raised in Sardis, Miss.

Nichols attended an American Missionary Association school, organized for freed men, in Memphis, Tenn., where he trained as a teacher. He taught for two years before enrolling in medical school. He graduated from Howard University Medical College in Washington, D. C., in 1899.

After graduation, Dr. Nichols moved to Quincy and opened a practice at 234½ N. Sixth. He married Annie M. Davis, who was a trained nurse, in 1901. They lived at 819 N. Eighth, where they raised three daughters.

Although Dr. Nichols only lived in Quincy about 20 years, he was involved in many organizations and for a time, was the only African-American physician in Quincy.

Whenever a spokesman or committee was needed, Dr. Nichols' name was included. The black community objected to the proposed location of Lincoln School in 1908.

Dr. Nichols and two other gentlemen presented a petition to the school board saying, "We consider it a menace to our welfare, as a people, to have our children educated in the vicinity of Adams row, which is the dwelling place of all manner of vice and crime and which is the rock of Gibraltar to the police station."

The Lincoln School opened in 1910 at its new location at 10th and Spring streets. Later, Nichols led a committee to talk to the school board about its decision to place all black children in Lincoln School regardless of where they lived in the city.

They said, "We have always had confidence in the honorable school board, believing that they were men above race prejudice. …" Unfortunately the people of Quincy were not above race prejudice, and the decision did not change.

When the Quincy chapter of the National Association of Colored People was organized in 1912, Dr. Nichols was elected president. He served in that post until the war intervened in 1917.

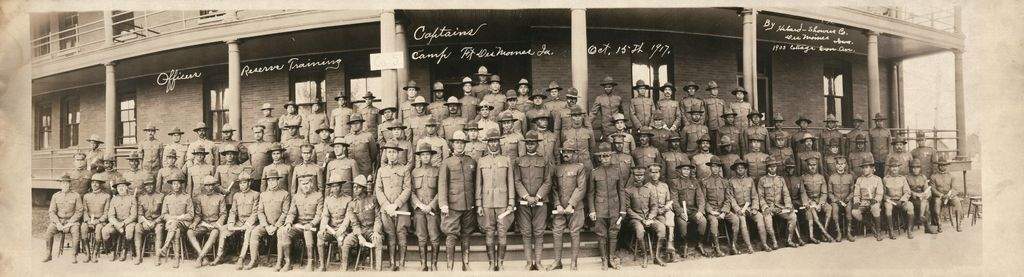

At the age of 47, he volunteered for military service, taking the exam for the Medical Officers Reserve Corps in July. He received his commission as first lieutenant in August and was sent to Fort Des Moines, Iowa, in September.

Fort Des Moines had been a cavalry training post but was converted to train African-American officers when the United States entered World War I. Dr. Nichols had 42 days of military training before he was sent to Camp Funston at Fort Riley, Kan. At Fort Riley he was assigned to the 366th Field Hospital of the 92nd Division 317th Sanitary Train. The 92nd Division was organized at Camp Funston in October 1917 and was an African-American division.

The 317 Sanitary Train was assigned to the 92nd and consisted of four field hospitals, four ambulance companies, each with 12 ambulances, and a medical supplies unit. The Buffalo Soldier Division was its nickname. It was sent overseas in July 1918, but by then, Dr. Nichols had left the service.

In February 1918 he was granted leave to go to his elderly mother who still lived in Mississippi. She was seriously ill. On his way south, he passed through Quincy, where local newspapers chronicled his trip. He returned to Camp Funston to work in the infirmary of the 317th Sanitary Train but resigned his commission about a month later.

Dr. Nichols explained his decision to resign from the military after only six months in a letter to the editor of The Daily Whig saving, "I find that conditions which need my attention at home are so pressing as to force me to surrender my most honored commission as first lieutenant, M.R.C., of the army of the United States."

He said his mother was a "hopeless and confirmed invalid," and decided that, "he who serves his country best is he who takes care of his family."

In a letter to the president, he promised "to do all I can for the cause of democracy." He goes on to address his fellow citizens of Quincy, "Here I wish to say to the men of my race in particular, not to lose any time, effort, or opportunity to assist our country in her hour of greatest peril. Our grievances may be many but this is not a time to nurture petty or personal spite."

Upon returning to Quincy, Nichols again engaged in civic activities. He was on the executive committee to plan a parade and activities in Washington Park for the 55 African-American draftees from Quincy. He gave the farewell address. The Aug. 2 parade consisted of the draftees, the Chauffeurs' Band, the Red Cross Unit, the War Relief Club and the Married Ladies Drill Team, among others.

After the war, Dr. Nichols was appointed chairman of the Negro Workers Advisory Committee of Adams, Hancock and McDonough counties. The committee was under the auspices of the Illinois State Labor Department. They were to help returning veterans.

Late in 1919, Nichols and his family moved to Detroit, which by the mid-1920s was the fourth largest city in the United States. Throughout the 1920s southern black migrants continued to move to the Detroit area. The health situation for this black population was poor. There was one hospital for black citizens. Smallpox, tuberculosis and pneumonia caused many deaths.

Dr. Nichols educated the community about health. He was invited to church pulpits to talk about hygiene and sanitation. He practiced medicine in Detroit for 15 years before dying April 21, 1936, at age 65.

Arlis Dittmer is a retired medical librarian. During her 26 years with Blessing Health System, she became interested in medical and nursing history--both topics frequently overlooked in history.

Sources:

Beckford, Geraldine Rhodes. Biographical Dictionary of American Physicians of African Ancestry, 1800-1920. African Homestead Legacy Publishers: Cherry Hill, N.J., 2011

"Dr. Hosea J. Nichols Receives Commission. Quincy Daily Whig, Aug. 28, 1917.

"Dr. Nichols Passes Army Examination." Quincy Daily Herald, Aug. 4, 1917.

"Explains Step." Quincy Daily Whig, March 31, 1918.

"Farewell for Colored Boys Friday, Aug. 2." Quincy Daily Whig, July 26, 1918, p. 3.

Fischer, W. Douglas and Joann H Buckley. "African American Doctors of World War I: The Lives of 104 Volunteers." Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company Inc., 2016.

Lamb, Daniel Smith. A Historical, Biographical, and Statistical Souvenir. Howard University Medical Department: Washington, D.C., 1900.

"Lieut. Nichols M.R.C. Here." Quincy Daily Journal, Feb. 14, 1918, p. 10.

"Name Dr. Nichols as Head Negro Committee." Quincy Daily Journal, April 17, 1919, p. 2.

"Object to School Site." Quincy Daily Herald, June 8, 1908, p. 8.

"Object to the Ruling." Quincy Daily Herald, Sept. 27, 1910, p. 12.