California or bust! Quincyan journeys west for gold rush

When James Marshall plucked "five or six pieces of shiny quartz" from a California stream in 1848, he likely had no idea that his actions would be the catalyst for the most significant movement of people since the Crusades. At the time he was more concerned with finding a good stand of lumber to build a saw mill. He didn't even return to John Sutter's Fort for almost five days.

However, when news of Marshall's discovery did get out -- and how could it not? -- hundreds of thousands of fortune hunters rushed to the West from all over the world. They came from China, Australia and Europe. In fact, due to the crude nature of both communication and transportation across the United States, many of the first "49ers" were foreign émigrés who heard about the discovery before those in eastern states.

These fortune hunters left jobs, homes, even wives and families. Entire cities, as well as hundreds of "hole-in-the-wall" mining camps, sprang up overnight. Most who came down with "gold fever" failed to strike it rich. Even John Sutter, on whose land the spark for the gold rush was lit, ended up bankrupt financially, as well as psychologically, by the experience. Many remained in California, drifting into occupations that would come to calm the unruly nature of the territory. Many more, having failed to hit the "mother lode," returned to their previous lives having experienced a great adventure.

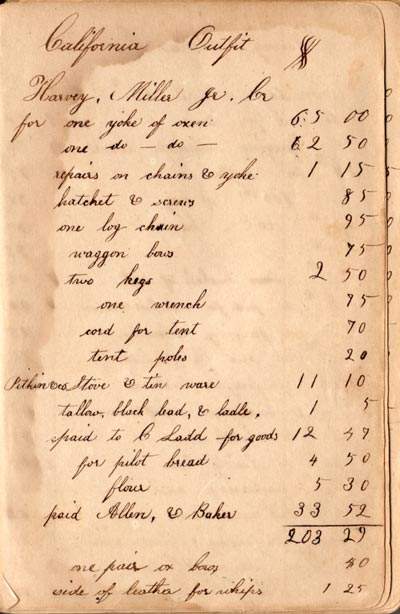

Harvey Miller, Jr. was one such "49er," although he did not make the trek west until 1852. We know the exact date and time of his departure for the gold fields because he kept a meticulous diary of his journey, which is preserved by the Historical Society. Miller was born in Connecticut in 1818 and, although no records exist indicating why he migrated to Illinois, it was in all likelihood similar to what motivated many Americans: the thought that something better was just over the horizon, the ubiquitous intangibility of the "American Dream." His journal begins, "April 28, 1852, Wednesday evening, left Quincy in route for California, crossed the river, and encamped at lone tree prairie."

Miller's journal is not significant because of the details it provides about the gold rush or, for that matter, California. He provides few details about the gold fields and prospecting once he arrives. Moreover, his account abruptly ends on Oct. 14, 1852, without explanation and with no details of his return to Quincy. What draws us in, captivates and holds our rapt attention, are the vivid, clear images of his westward trek. The trip west was difficult and not for the faint of heart. For the majority of those who dared, the trip was the most difficult, dangerous journey they would ever undertake. Averaging 15-20 miles a day, these 19th century nomads could expect the crossing taking six months.

On May 19, 1852, Miller's company is camped outside of Kanesville, Iowa. "I rode on ahead of the teams," Miller writes, "and went into Kanesville, where I found a perfect jam, so much so, that I had some difficulty in getting through the street." Kanesville, soon rechristened Council Bluffs, was the starting point for the Oregon and Mormon Trails and wagon trains could replenish supplies before "jumping off" into the Great Plains. There Miller and his group joined another band of "Quincy Californians," the Bowles and Butler Company. The combined number of westward emigrants was now approximately 35.

On May 25, as the group crossed into the unorganized territories, Miller observes, "We are now fairly in the plains, and see plenty of Indians of the Omaha tribe." Miller's opinion of the Omaha was less than flattering, "They are great beggars asking for money food or anything they fancy." He held the Pawnee, however, in higher regard. "They are a finer race of indians (sic), than the Omaha," Miller remarks, "many of them being well dressed after the Indian fashion, buffaloe robes, leggings and moccasins." Miller's group spent several days traveling up the Platte River, all the while "thronged with redskins" who were "well armed with bows and arrows," but Miller described them as friendly and did not feel that his party was in danger. Wagon trains west were more likely to fall victim to an accident or disease than an attack from a "redskin."

Tragedy struck Miller's company on June 2. Miller wrote "Dr. Kenesller was drowned" in the Platte River. He and several others had gone to bathe and, "not being able to swim," he was swept away by the current. They were unable to recover the body. They frequently passed emigrant graves, which served as macabre witness to the perils of the trip. "We see several graves every day, (unintelligible) is disnetery (cholera) caused by bad water." Miller observed that, while "the Platte country is the most beautiful I ever saw, it is the grave of the emigrant." On June 9, 1852, the party came across the grave of Mrs. Joel Emery. She and her husband had been part of an earlier train of California-bound Quincyans. This was the first grave of a person from Quincy the party had encountered. Miller's party would also lose someone to "the cholera."

On July 8, Miller got his first glimpse of the Rocky Mountains. "I was out in the hills today, and came in sight the rocky mountains, the tops are covered with snow." It was also on July 8 that his group parted with Bowles and Butler. According to Miller, there were "too many captains to get along well." On July 31, Miller arrived in Salt Lake City, the Mormons "New Zion." The Mormons had, until recently, called Illinois home, and many had converted to the faith. Stopping in Salt Lake to replenish supplies before undertaking the final push over the mountains, Miller remarked on the neat and tidy order of the Mormon city and described his meeting several "Illinois Saints" who seemed to be doing well.

Arriving in California almost four months after leaving Quincy, Miller immediately set to work. It was not, however, in the gold fields where he sought his fortune. Believing, perhaps, newspaper accounts that a hardworking, enterprising man was more likely to strike it rich by providing services to the miners rather than by prospecting, Miller and another man set about making shingles and boards for the thriving building industry in and around Placerville, Calif. Miller did try his luck at prospecting on at least one occasion, "a party of nine of us started on a prospecting tour up the south fork of the american river, we met with no success." The path to fortune would not be an easy one.

Miller's journal provides no information as to why, or when, he decided to return to Quincy. However, if history can serve as precedent, his frustration in not striking it rich, as well as missing his wife and children, likely played a role.

Miller returned to Quincy sometime before the Civil War and enlisted in the 2nd Illinois Cavalry. Attached to the Department of the Gulf Sent and sent to Louisiana, Miller survived the war -- another grand adventure. But that is a story for another time.

David Harbin is a history professor at John Wood Community College and serves on the Historical Society board. He has presented papers on utopian communal experiments at the Conference on Illinois History and written about the 19th century Latter-day presence in Illinois.

Sources

Brands, H.W. The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream. NY: Doubleday Publishing, 2002.

Miller Jr., Harvey. "The Diary of Harvey Miller (April – November, 1852)." The Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County (Quincy, IL).