Camps proved to be great conservation experiment

It was 1933. Giles Carr, a recent graduate in civil engineering from the University of Illinois, was looking for a job. However, 1933 was no ordinary year for young job seekers. It was in the middle of the most devastating economic downturn in American history, the Great Depression.

"I went all over the whole country looking for a job, but no go. You couldn't beg, borrow or steal a job," Carr said in an oral interview in 1982.

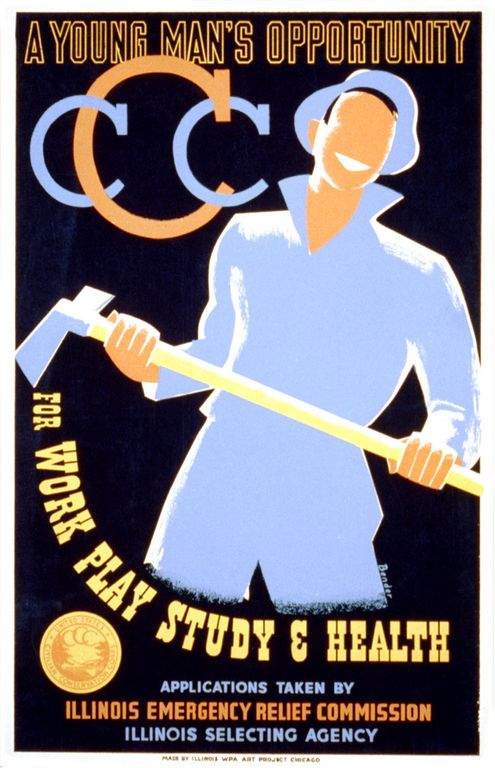

Fortunately for Carr, opportunity in the form of a new federal relief program came calling. Carr and other young men like him became integral parts of an historic New Deal program, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

One part work-relief measure, one part conservation project and one part youth program, the CCC was undoubtedly the New Deal's most unique and complex federal aid program. The idea was conceived by President Franklin D. Roosevelt while governor of New York (1929-32). "We know that a very hopeful and immediate means of relief, both for the unemployed and for agriculture," Roosevelt wrote, "will come from a wide plan of . . . reforestation."

Young men, ages 18-29, could enroll for six-month terms, live a semi-military life at a work camp, eat wholesome meals, receive health care and education, and work in various projects ranging from National Park construction to conservation and reforestation efforts. Enrollees were paid $30 a month for their labor, $25 of which was sent home to needy loved ones.

Within four months of Roosevelt's presidential inauguration in 1933, the CCC operated 1,463 camps with 250,000 enrollees. Roosevelt's "tree army" as it became affectionately known, was up and running, eventually coming to Adams County in July 1934. Company 1681 set up camp in Camp Point to work on drainage and private land erosion projects on local farms. The camp's setup and operations were identical to nearly all CCC camps, thanks in part to the U.S. Army's administrative role in the program. Each camp was a temporary community, structured to have barracks (initially Army tents) for 50 enrollees each, officer quarters, a medical dispensary, mess hall, recreation hall, educational building, lavatory and showers, administrative offices, tool room/blacksmith shop and garages.

The work of Company 1681 ushered in the soil conservation movement in Adams County. Before this time, some terracing, contouring and pasture improvement had been done by pioneering farmers. Now, under the newly formed Adams County Soil Conservation Association's (ACSCA) watchful eye, work such as strip cropping, drainage, wood lot improvements and waterway construction could begin in earnest using federal manpower and resources.

Local farmers interested in conservation could apply to the ACSCA. Local experts, called LEMs or Local Experienced Men, would oversee the CCC enrollees in their tasks, teaching them valuable trade skills.

This aspect of the CCC impressed one participant, Steve Nosser, the most. "I learned a whole bunch of skills. How to drive a truck and a bulldozer. Later, I learned how to jackhammer and dynamite rock at a quarry."

Most CCC veterans used these trade skills throughout their later work in World War II and in postwar careers.

Camp Point's CCC camp ended in 1937, but it wouldn't be long until the CCC returned to Adams County, with a camp for Company 1660 setting up residence in Quincy on July 1, 1939. Occupying land owned by the Arrowsmith family at 30th and Broadway streets, the 30-acre camp was identical in setup to Camp Point. As reported by The Quincy Herald-Whig, the camp commander was First Lt. Clarence Bos, and former Quincy Mayor J. Emmett Wilson was Army inspector of Illinois camps.

Life at Camp Quincy followed a set pattern of events. Reveille at 6:30 a.m. started the day, followed by breakfast, then transportation to the work site at 8 a.m. After a midday break for lunch, work resumed until 4 p.m., followed by a return to camp, formation and retreat, dinner, and finally a free evening period in which enrollees were encouraged to take vocational and educational classes. Without exception, lights out occurred at 10 p.m., with taps at 10:15 p.m. As one CCC published booklet stated, "There is nothing like the regularity of camp life to put a young man in good physical shape and good spirits."

Camp regulations were another large factor of life at Camp Quincy. The CCC leadership expected the men to act in a courteous manner, refrain from profane language, respect the chain of command, maintain neat barracks, dress in clean and proper uniforms, and bathe regularly. Most CCC enrollees in Quincy were neither troublemakers nor instigators, and few had problems with the program's rules.

The work of Quincy's CCC camp also followed the work of its Camp Point predecessor. Local farmers applied for needed natural conservation work, the ACSCA then prepared conservation surveys of land use and when approved, work was conducted by the CCC.

Per Giles Carr, 85 farms were assisted by the program, including the Cornwell, Kay, Allison, and Duncan farms of Adams County.

Quincy's camp stimulated the local economy. Supplies for the camp were purchased from local merchants. LEMs could find temporary employment with the camp, and the young men paid for local amusements using their $5 a month allowance. The Quincy Herald Whig reported, "Many Quincyans remember them rolling into town for an evening's fun."

The CCC, the greatest conservation experiment of its kind, ended June 30, 1942, when Congress denied funding for 1943 operations. This action, considered a mistake by many, was certainly no surprise. As a world war loomed on the horizon, the country focused its attention elsewhere. But the CCC had achieved its place in history. During the nine-year span of its operation, the CCC planted nearly 3 billion trees, constructed a million miles of roads and forest trails, and transformed the lives of over 2 million men. The CCC camps of Adams County may be long gone, but their worthy legacies of youth education, work relief and pioneering natural conservation are gratefully remembered.

Roberta Hirstius received her master's degree in American 20th Century and public history at Loyola University Chicago. She has worked at the National Archives Great Lakes office, the Swedish American Museum, the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian and the American Medical Association.

Sources:

Bradshaw, Bill. "CCC Boys, where are they now?" Quincy Herald-Whig, July 20, 1980.

Carr, Giles. Oral history interview by Jean Kay. Typed transcript.1982. Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Cohn, Stan. The Tree Army: A Pictorial History of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942. Missoula, Mont.: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1980.

People's History of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois: A Sesquicentennial History, edited by Rev. Landry Genosky, O.F.M. Quincy, IIl.: Jost and Kiefer Printing Co., nd.

Leake, Fred E. and Ray S. Carter. Roosevelt's Tree Army: A Brief History of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 6th ed., edited by Richard A. Long and John C. Bigbee. St. Louis: National Association of Civilian Conservation Corps Alumni, 1987.

Lebergott, Stanley, "Labor Force, Employment, and Unemployment, 1929-1939: Estimating Methods, Monthly Labor Review, (July 1948): Pages 50-53.

McElvaine, Robert S. The Great Depression: America, 1929-1941. New York, N.Y.: Times Books, 1984.

Moore, Robert J. "The Morrow Brothers of Macomb, Illinois and the Civilian Conservation Corps," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, v.104 n4: 336-369.

Salmond, John A. The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1967.

Schlesinger Jr., Arthur M. The Coming of the New Deal: The Age of Roosevelt. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958.

"Several New Buildings are Up at Camp." Quincy Herald-Whig, July 6, 1939.

"Three Barracks at CCC Camp are Now Completed."Quincy Herald-Whig, July 16, 1939.

"We Can Take It: A Short Story of the CCC." NACCCA Journal, February, August, September 1995.

"Wind in the Trees: The Story of America's Conservation Corps." NACCCA Journal, August 1993.