Capture, Trial, and Prison

Part 3-Capture, Trial and Prison

One can

imagine how excited George Thompson, James Burr and Alanson Work were as they

rowed across the Mississippi River from Quincy to Missouri that July evening in

1841. At last, they would help slaves escape from slavery. They took no

precautions to protect themselves. Thompson stayed with the boat at the water’s

edge while Burr and Work walked to the designated thicket to meet with the

slaves they had talked to earlier. Little did they know they were surrounded

and watched by armed men the entire time.

It was a strange encounter from the beginning. Because no black person could testify in Missouri court, the slave Anthony had been taught several questions to ask Work and Burr. The abolitionists didn’t notice that Anthony spoke very loudly when he asked where they were being taken and why. In answer to Anthony’s questions, the naive abolitionists explained the runaways would travel by night and be hidden by friends during the day until they came to a great lake where they would be taken by boat to freedom in Canada. Slavery was no longer legal there. The slaves would live free. After he had asked all of the questions he had been taught, Anthony gave the signal he had memorized. He said in an overly-loud clear voice, “We will be governed by your directions.”

They started to walk toward the river as the posse of slaveholders emerged from the surrounding brush cocking their rifles and shotguns. Work and Burr were surprised the slaves they were trying to help grabbed them and held them tight for the posse. They were quickly subdued.

Thompson was easily taken at the river. He, too, was shocked when the slaves who came to the water’s edge didn’t jump into the boat. Instead they held it tight to the shore as Thompson pled in vain. The armed men took him into custody.

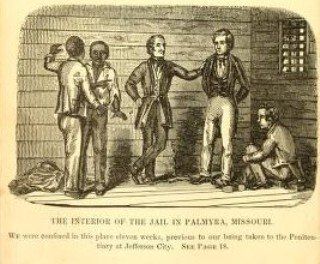

The three Quincy men were held overnight in William Boulware’s house. The next morning they were paraded into Palmyra – and it was a parade. Word spread throughout Marion County like wildfire. The families of the posse joined the procession and others entered along the route. Once in the county seat the three were held in the town’s log jail. It was a very secure building, being two log structures, one built inside the other with the space between the walls filled with stone rubble to make escape difficult. For extra security, the men were chained together and anchored to the wall. People flocked into town from the countryside to get a look at the abolitionists. They could peer through the barred window at the hapless men.

Justice moved quicker in the 19th Century than today. The men went to trial in September of 1841, just weeks after their arrest. The result was a foregone conclusion. Unlike today, when we take great care to try to make juries representative of the community, the sheriff hand-selected a “blue ribbon” jury composed of important men in the community. Six of the twelve were slaveholders, including John Marshall Clemens, father of the boy who would grow up to write as Mark Twain.

There was no law in Missouri regarding enticing a slave to run away. The three men were charged with simple larceny – theft of property. The jury instruction from the judge to the jury sealed their fate. He instructed the jury that if the slaves had taken “one step” with the abolitionists they were guilty of the crime. (You can read the jury instructions in the appendix of, Searching for Jim, Slavery in Sam Clemens’s World .) They were sentenced to 12 years in prison.

Thompson, Work, and Burr were failures at freeing slaves. But their foolish and naive mission did more for escaping slaves than a success ever could have. They accomplished three things. That night Anthony and the slaves realized they had been wrong. One of them, perhaps it was Anthony, we will never know, went to the open barred window in the dark of night and apologized to the three. He explained that the slaves knew nothing of abolitionists and Canada. From that day, word spread among the enslaved that there were people across the river in Illinois that wished to help runaways.

The second accomplishment was that it cemented the idea in the minds of Missouri slave holders that their slaves were loyal and wished to remain slaves. Slaveholders, by and large, believed their slaves were happy under slavery. It was a lie, but they did not give it a lot of thought. The action of Anthony and the other slaves in coming to a master proved to them their slaves were content. After 1841 runaway slaves in Missouri relied on other slaves and the few free black people who lived in Northeast, Missouri for assistance. This provided great cover. Whenever a slave would run off, the local authorities would immediately go off searching for white abolitionists who had “duped” another slave into leaving. As late as the beginning of the Civil War, the case of Thompson, Work, and Burr was being cited in the Northeast Missouri press as proof that slaves were loyal and would never raise a hand against their masters.

The greatest impact Thompson, Work, and Burr had was upon the abolitionist movement. Thompson proved to be an excellent propagandist and the three became national stars. Within a week a letter from him appeared in William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator . He cast himself, Work, and Burr as new Christian martyrs suffering like the early Christians in the “dungeon” of Marion County. He kept up a lively stream of letters and later wrote of their experiences in the book, Prison Life and Reflections , which became a must-read among abolitionists. He inspired countless people to take up the work of resisting slavery.

Though they failed in achieving their goal, their conduct as prisoners, their continued adherence to their beliefs, and Thompson’s constant promotional work kept them the focus of the abolitionist world. Thompson kindly assigned the income from the book to Alanson Work to help support his family. The three men served five to five-and-a-half years in the penitentiary in Jefferson City before they were paroled following a national campaign on their behalf.

Sources

Dempsey, Terrell. Searching for Jim, Slavery in Sam Clemens’s World. Columbia, MO:

University of Missouri Press, 2003.

Palmyra Missouri Whig , July 17, 1841.

Palmyra Missouri Whig , September 25, 1841.

Circuit Court records of Marion County, Missouri.

Liberator , August 27, 1841.

Liberator , October 8, 1841.

Liberator , November 5, 1841.

Liberator , December 10, 1841.

Thompson, George. Prison Life and Reflections . Hartford, Conn.: A. Work, 1853.

https://www.weather.gov/timeline