Card playing proved contentious in early 20th century

Ever since their introduction by Spanish explorers in the late 15th century, American card games have been a popular pastime offering challenging and creative play. Ambivalence, though, has plagued their history between being recreational and what some moralists called the "Devil's Deck." These reformers dubiously used the Bible -- which neither mentions cards nor gambling -- to denigrate an illustrated set of parchment that has existed in some form for over 1,200 years.

The Rev. Parker Shields of Quincy's Vermont Street Methodist Church was one who equated card playing -- with no money exchanged -- with gambling and guilt. In a sermon delivered in January 1902, he told his congregation: "Saw the card table in two and the chances are that a gambler will be reaped from the home. You say there can't be any harm in an innocent game of cards? The Devil has been at work for 6,000 years and likes to hear such arguments." The Quincy Methodist called women whist players "gamblers" and stated "the pit yawns for gamblers." Unlike in Missouri, Illinois law did not consider social card games and parties gambling, even when winners received lavish prizes. And without a home rule on the books in Quincy, they were not prosecuted until after a revival in Camp Point, when devotees of the controversial evangelist Billy Sunday (who said, "Card playing at home is worse than regular gambling") formed the Civic Federation of Quincy in January 1905. This group slated candidates for mayor and aldermen who would ban all card playing. Although the Federation did not win the mayor's office or a majority of the council one year after its incorporation, under the administration of John A. Steinbach, the front-page headline of The Quincy Whig read, "Quincy Makes First Raid on the Gamblers."

This was a token gesture, for in 1902 Quincy's German community had formed the Quincy Skat Club, after Germany's national card game, and elected Mayor Steinbach as president. The club estimated that over 200 people in the Gem City played skat, deemed the "most thinking of games." Catholic churches and organizations, such as St. Francis Solanus Church, St. Rose of Lima Church, the Western Catholic Union and St. Boniface Church continued to hold regular, well-attended card parties as fundraisers -- omitting them, though, during Lent. Many Protestant churches reviled this practice and demanded raids on these "social" card games, as this editorial the Rev. Pathfinder Sheldon of Quincy declares: "There is no distinction between the church fair raffle or whist party and the gambling den of the poker fiend… . We want the grand jury to enforce gaming law."

Contention continued until April 1917, when Quincyans elected John A. Thompson as mayor; he immediately issued an "ultimatum to the gambling fraternity that all forms of gambling are to be prohibited while he is the city's chief executive." One week after his election, in corroboration with Quincy's chief of police, George E. Koch, he clarified his announcement to include all card games.

This decree, though, lacked public support and the means to enforce it. Also, Allied and Central Powers were fighting throughout Europe in the War of 1917 (later known as World War I), and after the U.S. joined the Allies on April 6, 1917, local attention swiftly turned to the war. The John Wood Women's Relief Corps held a card party in November 1917 to fund a new ambulance for the War Department and later the Order of the Eastern Star -- a Masonic organization -- sponsored one for the Red Cross' benefit.

In WWI's aftermath, the exuberant 1920s brought a new schism to card playing in Quincy. Bridge became the most popular card game in "polite society" -- a euphemism for upper class. Bridge matches, with their accoutrements of tea and hors d'oeuvres, clashed in the social milieu with the "smokers" of low-life games. Bridge clubs formed in Quincy's more affluent neighborhoods -- Grove Avenue Club, Out Our Way Club and Collegiate Bridge Club. At the Quincy Country Club, winning players made losers prepare luncheons for them.

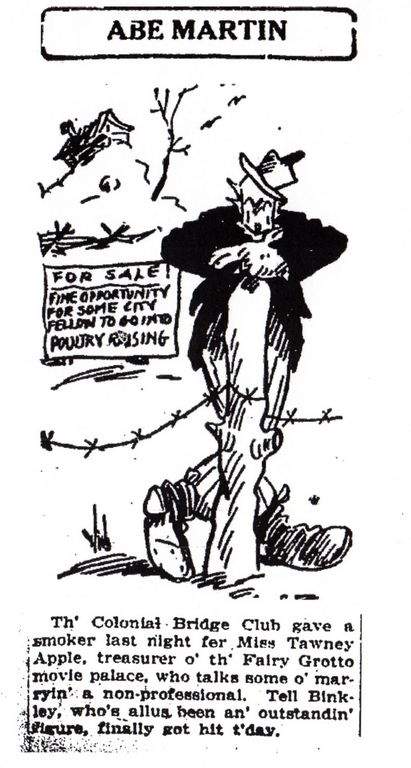

Kin Hubbard's cartoon "Abe Martin in Brown County," syndicated in The Quincy Daily Journal, satirized this class consciousness in 1924 by depicting a young man hanging like a scarecrow in a farm field with the caption: "The Colonial Bridge Club gave a ‘smoker' last night for Miss Tawny Apple … who tells of marrying a non-professional."

More controversies arose over card games for youngsters. During "Father's Night" at Jefferson School's Parent-Teacher Association in January 1917, Judge Lyman McCarl, who presided over Adams County Delinquent Court, stated that children's playrooms in Protestant churches needed to emulate Catholic ones, which permitted card playing, and provide this recreation. He cited Cheerful Home, where since its founding in 1888 card playing had been allowed. "I have seen 150 boys playing cards in that room and at home. When boys play cards in a room like that room and in their homes we know they are not doing devilment on the street." Protestant churches, though, held fast to their prohibitions, and in March 1925 the Quincy Board of Education banned cards in public schools "fearing that allowing card playing might set a troublesome precedent."

After the Great Depression began in 1929, much of the contention about card playing waned. Survival became paramount, and a greater tolerance emerged for this recreation as a respite from life's struggles. On June 16, 1932, the Quincy City Council sanctioned the purchase of the Lorenzo Bull house for the new Women's City Club, where card playing was to be a mainstay of its activities and fundraising.

After Illinois legalized parimutuel horse race betting in 1927, some citizens even saw gambling as a legitimate way to bolster the economy, and groups such as Quincy's East End Poker Club came out of the shadows and began announcing its gatherings in local papers.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer and photographer whose work has been widely published as a contributor to literary magazines, as a correspondent for Catholic Times, and for the past 23 years as a writer for the Library of Congress' Veterans History Project.

Sources:

"A Sample of Billy Sunday." Quincy Daily Herald, Feb. 13, 1906, Page 5.

"Abe Martin." Quincy Daily Journal, April 27, 1924, Page 3.

"All Games Look Alike." Quincy Daily Herald, Nov. 29, 1900, Page 4.

"Board of Education Forbids Card Game in Public Schools." Quincy Daily Herald, March 11, 1925, Page 12.

"Civic Federation of Quincy." Quincy Daily Journal, Jan. 27, 1905, Page 2.

"Gambling in All Forms Gets K.O." Quincy Daily Journal, May 8, 1917, Page 2.

Hargrove, Catherine Perry and U.S. Card Playing Co. ed. A History of Playing Cards and a Bibliography of Cards and Gaming. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, 2008, Pages 279-80.

"Mayor Thompson Against Gambling." Quincy Daily Herald, April 30, 1917, Page 5.

"Quincy Makes First Raid on the Gamblers." Quincy Whig, Jan. 18, 1906, Page 1.

"Shields and Card Playing." Quincy Daily Herald, Jan. 27, 1902, Page 2.

"To Organize Skat Club." Quincy Daily Herald, Jan. 23, 1902, Page 5.

"Urges Advisory Board for Q.H.S." Quincy Daily Whig, Jan. 20, 1917, Page 7.