City rallies, saves itself from menace of cholera

A slim ledger in the library of the Historical Society records a time when the people of Quincy came together -- businesses, citizens and government united to protect the city from a deadly and terrifying situation.

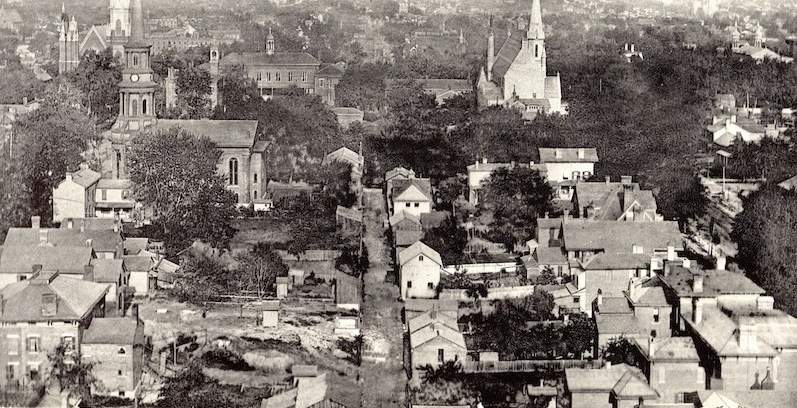

In the early 1890s, most cities had problems keeping up with the demand for services. Services such as sewers, clean drinking water, street maintenance and refuse removal lagged far behind what was needed. This, for the most part, was accepted as normal. It was a time when personal hygiene also followed standards quite different from today.

"You can almost gamble that out of ten men that pass you in the street not more than two on an average make a business of bathing the body once a week," said the Quincy Daily Herald in 1893.

The previous summer, Quincy and the world watched in horror as the Asiatic cholera began spreading across Europe, leaving thousands dead in its wake. There was no known cure and much debate about the way the disease spread, but authorities agreed that it was fostered by unsanitary conditions and carried by travelers.

Many European visitors were expected as America was set to host the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, where huge amounts of money had been invested, and hopes were high for visitors and profits. Debate about preventive measures raged as fear spread. Illinois would be especially affected.

Travelers arriving in Boston from Russian ports were stripped, bathed in a solution of water and carbolic acid and their effects were fumigated. Canadians feared infected passengers from Germany from the Hamburg-American steamships that arrived weekly. The state of Illinois implemented its quarantine order from the Board of Health and appointed inspectors for all trains and ships.

By Sept. 1, 1892, cholera arrived in New York aboard the steamship Moravia from Hamburg, Germany. Twenty-two people died during the 10-day Atlantic crossing, and two were recovering. The ship flew the yellow plague flag. Of the 22 deaths, all were passengers in the crowded steerage class, and 20 were children. The dead were buried at sea. There was talk of stopping all immigration during the crisis.

In Quincy, health officer Hazelwood called for an advisory panel of doctors and a citywide cleanup. Specific problems cited included one within 125 feet of Washington Park that contained, "ash heaps, restaurant slops, old tin cans, standing water, old shoes, old rags, old straw and no one knows what else." The alleys and many of the streets in town were full of refuse.

Over the fall and winter, the members of the city considered, and by late winter, had determined, a course of action.

The Quincy Daily Whig on Feb. 29, 1893, reported: "Quincy will be cleaned up in the spring as it has never been cleaned before, if money, energy and law can do the work. The city authorities have the moral support of the citizens in their war on filth and what is a great deal more to the purpose will have their financial assistance. The city has plenty of law to enforce the removal of filth and the abatement of nuisances, but is handicapped by the lack of funds with which to carry on the war. Its weakness in this respect will be strengthened by the business men and manufacturers and as soon as the frost is out of the ground a crusade for cleanliness will be commenced, which will be continued till there is not a spot in the city to welcome cholera."

In February 1893, S.H. Emery and the Young Men's Business Association called a meeting, supported by six manufacturers: the American Straw Board Co., Taylor Bros., Comstock-Castle Co., Gardner Governor works, Channon, Emery & Co. and the Smith-Hill Co. Each of these companies pledged a substantial donation to pay for health officers called sanitary police.

The city would be divided into 12 districts, and each officer could write citations for hazards, which the homeowner would need to clean up. It was made clear that the money raised would be used to hire inspectors and compel owners by law to complete the cleanup. The fund was not for actual cleanup work.

Contributions poured in. Some businesses gave the use of wagons and men; Stern & Sons contributed 2,000 gallons of disinfectant.

There were problems and controversy. There were only two vault (outhouse) cleaners in the city, who charged $30-$50 per cleaning. Compare this to Quincy's 4,000 outhouses, many of them too close to home cisterns that supplied drinking water, and the scope of the problem becomes clear. For years there had been no funding to enforce city ordinances. This meant that illegal dumping, outhouses that connected to the sewer by running though the gutters, storm drains that were plugged, etc., made perfect breeding grounds for disease.

"The reports of filth of all descriptions, the harbinger of disease emanating from all parts of the city was something astounding," reads the note in the sanitary police account ledger.

The sanitary police set to work, and by the end of April had inspected 5,842 sites and issued 2,684 notices to abate a nuisance. A total of 1,518 loads of "filth" were deposited at the city dump during April. This was followed by 2,000 additional loads by the end of May.

The cleanup effort worked. The city avoided a cholera epidemic that could have decimated the city and destroyed prosperity for a decade. Twenty years later in 1915, a city-wide cleanup, prompted by another cholera scare, took only three days rather than the three months spent in 1893. It is a good reminder that our city can and always has pulled together in times of crisis.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson. She is executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

Financial Record Quincy Sanitary Committee 1893-1895 – Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

"A Misapprehension," The Quincy Daily Journal, March 4, 1893.

"An Eye-Opener for Those Sanitary Inspectors," The Quincy Daily Journal, March 21, 1893.

"A Special Meeting," The Quincy Daily Journal, Sept. 3, 1892.

"Board of Health," The Quincy Daily Whig, May 30, 1893.

"Cholera is Coming," The Quincy Daily Herald, May 17, 1893.

"Cholera is Feared," The Quincy Daily Herald, Feb. 18, 1893.

"Clean Up Campaign Just Closed Recalls Another," The Quincy Whig, May 9, 1915.

"Leading a Crusade," The Quincy Daily Herald, Feb. 28, 1893.

"Make War on Filth," The Quincy Daily Whig, Feb. 28, 1893.

"Spread of the Cholera," The Quincy Daily Whig, July 10, 1892.

"The Board of Health," The Quincy Daily Whig, April 25, 1893.

"The Chicago Fail," The Quincy Daily Whig, Jan. 20, 1893.

"The Cholera," The Quincy Daily Journal, Aug. 25, 1892.

"The Cholera," The Quincy Daily Journal, Sept. 1, 1892.

"The Situation," The Quincy Daily Journal, Sept. 7, 1892.