City's last public hanging took place in 1927

Several months ago The Herald-Whig printed a story about the gallows used in Illinois’ last public hanging — that of Charlie Birger in Benton in 1928.

A year earlier, on April 29, 1927, the city of Quincy also experienced its last public hanging.

According to newspaper reports, Thomas Twine had pleaded guilty to shooting and beating his girlfriend, Lillian “Lillie” Jackson, to death on Nov. 11, 1926, in their apartment at 833 Jersey. Witnesses and police reports stated that Twine had committed the deed, then gone to a service station at Ninth and Jersey and called the police, saying, in essence, “Come and get me.”

On Valentine’s Day, 1927, Judge Fred Wolfe, after explaining that he had exhausted every avenue to prevent declaring the death penalty, proclaimed, “….on April 29, between the hours of 10 and 4 you will be hanged by the neck until you are dead, in the court house, or in an enclosure, and the sheriff (recently-elected Kenneth Elmore) is hereby instructed to do this.”

Twine’s defense attorneys had worked hard to change the judge’s mind.

One stated, “Only One has a right to take life and that is the One who gave it.” The other, in the culture of the times, told the court: “Twine [a black man] belongs to a race that has not had the advantages which the white man has.”

Doubting that Twine realized what he had done, he went on to say that “while he [Twine] is not insane nor yet a moron, he is below normal.”

Messages Twine wrote as the end drew near seem to belie this judgment. Nevertheless, the sentence was pronounced. In the ensuing 74 days, held without bail, Twine proved to be a model prisoner, becoming a friend of the jailer, Bert Buffington.

A petition was sent to Gov. Len Small to rescind the sentence, to no avail.

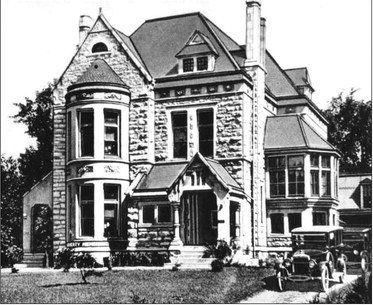

On the morning of April 29, a makeshift gallows had been erected inside the courthouse. Ministers of the three black churches in town, along with a friend, came to see Twine, all ushered in through the heavy doors into his cell.

Later, another minister joined them.

In an odd twist, Twine

had asked for a pink carnation. Sheriff Elmore brought several, and Twine selected one. It was pinned on his left lapel. Soon Deputy Kirby Hill joined the group. Twine, holding him to an earlier promise, asked, “You’re going with me, Kirby, all the way?”

Kirby answered, “You bet I am, Tommy.” The long narrow cell was filled with cigarette smoke and small talk. At 9:45, Twine looked out to see an old friend. He said, “Bert, True Osgood’s outside. Could he come in?”

Bert answered, “Sure. Tommy.”

Talk in the cell was subdued as the 10 o’clock hour approached. Then a stern-faced crew stepped in: Sheriff Elmore, Deputy Kirby Hill, jailers Pete Hartman and Walter Cox, and the hangman, G.P. Hannah, who had performed this grisly task

over 50 times around the state.

Twine had earlier written a note to his lawyer: “I am going to a better world.

I have made my peace with God and he is calling me home. I am paying a debt that all is got to pay.… I am going home.… Being a prisoner of the Adams County courthouse, I wish to thank the jailer, Mr. H. Buffington, and my cellmates for the kindness shown me while here.”

During this time, L.M. Kayton operated a restaurant at 224 Fifth, and his 4-year-old daughter, June, brought Twine his last few meals. One day Twine pressed a note in her hand, saying, “Here is a note, little girl. Keep it as a remembrance of me and as a reminder to do right always.” Inside was this statement: “Name Tommy Twine, born four miles south of

Louisiana, Missouri, On August 11, 1891. I will be Friday 35 years, 7 months, 18 days. Leave mother Mariah Twine, Brother John Twine, Brother Homer Twine, Anthony Twine, Octave Twine, and sister Sarah Twine. Wife Sarah Sue Twine and Girl child Frances Dudina Jackson Twine. Dear Sister, I am going home never to return. Please raise the little girl up all right…. I must close. May God bless you all three. I hope I meet you all in Heaven. Be good and pray for me. Thomas Twine” Twine led a procession down the jail hall. He put his cuffed hands through the bars, saying, “Goodbye. Good luck.” Then Hannah interrupted the proceedings to explain the protocol. In a calm voice he explained that he had marked a chalk line on the scaffold and that it would be easier if Twine would just step on that line when he was told to take his place, demonstrating the procedure. Twine smiled and said that he would he do as asked.

Back at the cell, he was met by those who had been with him earlier. The procession moved through the jailer’s room and into the hallway toward the execution room. As he reached the steps, Twine was calm.

He shook hands with all present. When asked if he had anything to say, Twine answered, “I made quite a grand fight. Bless all those people who tried to help me. I bid you all goodbye….”

He hesitated, then added, “I believe that is all I have to say.”

All the spectators that day could see only the platform and steps leading up to it. Twine walked up the steps and to the chalk line, as he had been instructed.

He was on the trap. Hannah supervised as Sheriff Elmore and three deputies strapped his arms and legs. Four doctors, led by Dr. C.D. Center, were present. A 12-man jury, picked by the sheriff, was seated on both sides of the scaffold, beyond the door of the corridor, out of sight of the other spectators.

When everything was ready, at 10 a.m. April 29, 1927, the sheriff sprang the trap and Twine’s body dropped 7 and a half feet.

At 10:07, Twine was pronounced dead. A “sheriff’s return” was signed by the sheriff, all the doctors, and all the jurors who had witnessed the event, and turned over to the clerk of the circuit court, who made it a part of the records of the Twine case.

The body was later taken to the Daugherty Memorial Home, where it was prepared and sent to his hometown of Louisiana to be buried, thus ending the saga of Quincy’s last hanging.

Dwain Preston is a native of Pike County. He taught in the Quincy Public Schools, at Quincy College and at Culver-Stockton College. He recently retired from Quincy Notre Dame High School and John Wood Community College as an adjunct professor.