Family's affection tested by scandal that rocked the state

In the Illinois Governor's Mansion in Springfield on the morning of Nov. 27, 1856, Lydia Olivia Matteson sat stiffly on a horsehair-covered English Regency sofa.

Like her mother's and sisters', Lydia's black hair was parted in the middle and pulled back so tightly it exposed a thin, straight line of scalp on the crown of her head. Covering her ears, it wrapped her face in a long oval frame. The young woman's eyes bore none of the translucence of the eyes of her father, Gov. Joel Aldrich Matteson, but were more like the dark, brooding-but-patient eyes of her mother, Mary.

On this day, 27-year-old Lydia Matteson waited alone in an upstairs parlor of the 28-room mansion to be married to a young Quincy upstart banker, John McGinnis Jr. Her sister Clara judged her reserved and undemonstrative like their mother. Finished at Monticello Female Academy in Godfrey, a woman of charm and beauty, Lydia Matteson was prized among Springfield's elite. Yet her affection did not easily find expression, sister Clara wrote, except for one suitor. Her heart was "full of love" for McGinnis of Quincy.

McGinnis, 25, was just as affectionate for Lydia Matteson. But when he asked for her hand, her parents refused. They had information that the state senate had ordered his arrest in 1852 for refusing to answer questions about allegations of fraud.

For Lydia Matteson, it was as if life had ended. She retired to her room, declined suitors' invitations and avoided the extravagant dinners, parties and entertainments the Mattesons organized in the mansion. With their daughter despondent, the Mattesons relented to the proposal by McGinnis.

Lydia's friend, Mary Lincoln, had hoped for a party before the families moved. Matteson was nearing the end of his term as governor, and the McGinnises planned to move to Quincy. But Lincoln knew the girl. "Lydia has always been so retiring," she wrote, "that she would be very averse to so public a display."

The McGinnises moved to Quincy where, in just a few years, their affection would be tested by a public scandal that rocked the family, a Quincy bank and the state.

Joel Matteson had been elected governor of Illinois in 1852. He moved his family from Joliet to Springfield, where the state offered a cobbled up old public works building for the governor's residence. Matteson refused to move his family into it, taking rooms instead in the St. Nicholas Hotel. He pressured legislators to build a new mansion and pre-empted its location, paying Abraham Lincoln's first law partner, John Todd Stuart, $3,000 for a large lot across Jackson Street from Stuart's home. The McGinnis-Matteson marriage was the first wedding in the mansion.

Matteson and McGinnis shared an ambition for making money. By the time Matteson, a New Yorker, reached Illinois in 1834 with his wife, nee Mary Fish -- a relative of the celebrated New York politician Hamilton Fish, Matteson was wealthier than when he left. He had stocked his wagon with a large supply of shoes and boots and sold them to pioneers along the way to Illinois. In Joliet, where he and his family settled in 1849, he started the successful Matteson Woolen Mills, opened a mercantile business and founded the Merchants and Drovers Bank, the first onc in the city. Daughter Clara recalled he grew "independently well off" in canal and rail contracting, real estate speculation and banking. He also founded banks in Peoria and Shawneetown.

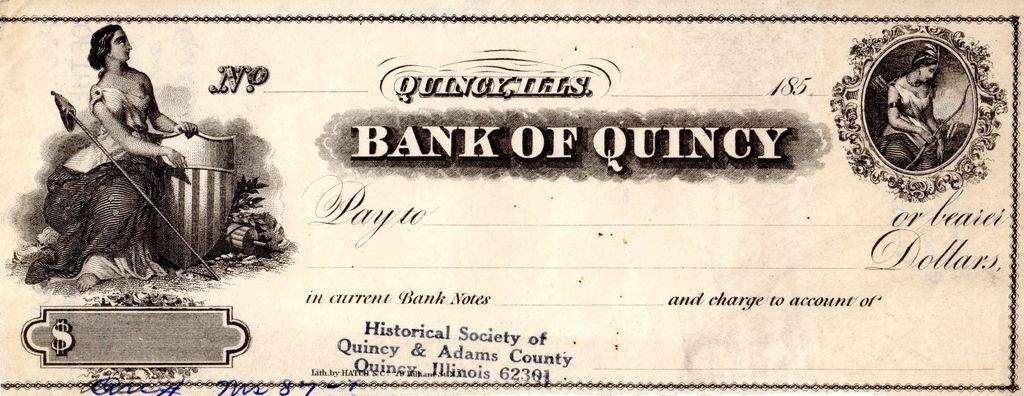

Matteson in 1856 became the lead investor in McGinnis' "Bank of Quincy," which opened that year on the first floor of the Quincy House at Fourth and Maine streets. City directories show McGinnis was the bank's president during the first two years and cashier afterward. The bank started with capital of $200,000, positioning it well among Quincy's three financial institutions. The two older banks -- Flagg and Savage and Moore and Hollowbush -- fell to the financial contractions during the nation's Panic of 1857 and by 1858 had permanently closed. That left a virtual monopoly for the Bank of Quincy, and for a time it prospered. By 1860, however, it too suspended operations. Scandal, as well as financial maladies, was among the causes.

Shortly after Matteson had taken office as governor, he appointed Josiah McRoberts to the Illinois-Michigan Canal Commission. In 1853, McRoberts asked Matteson to take two wooden boxes and a shoebox of redeemed and unissued canal scrip from Chicago to Springfield for deposit with the state treasurer. The scrip, issued by the commission to buy Illinois bonds that financed the canal's construction, disappeared until 1856. In November, $13,000 in scrip was presented for new state bonds. An additional $93,500 was presented for the same purpose in 1857. In 1859, Jacob Fry, an early canal commissioner, became suspicious when he learned that canal checks were being offered for sale in Springfield. He warned State Treasurer Jesse K. DuBois of possible fraud.

Shock swept the state when it was revealed that former Gov. Matteson had been redeeming the scrip. By the time the matter became public, he had exchanged $223,182.66 in scrip for bonds. There followed investigations by the Legislature, a three-member special commission that included Quincy lawyer Orville Browning, and a Sangamon County grand jury. Despite overwhelming evidence, Matteson escaped charges. He acknowledged having acquired and cashing the scrip but denied wrongdoing. He said he could not remember the name of the seller. Matteson said he would pay the state back just to preserve his reputation.

From the steps of the Sangamon County Building in 1863, several of Matteson's properties were sold, including a three-story brick building on the west side of South Fifth Street between Ohio and Delaware in Quincy. It brought $25,000 of the $238,000 raised that day. With the restitution, the pursuit of Matteson for embezzlement ended.

McGinnis and partners supplied food and hospital supplies to the Military District of Illinois during the Civil War. President Andrew Johnson appointed him ambassador to Sweden in 1866, but the Senate rejected his appointment. John and Lydia McGinnis were married 42 years and had five children before they died, she in 1898 and he in 1901. They were buried in Joliet.

Reg Ankrom is a member of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County. He is a local historian, author of a prize-winning biography of U.S. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on Douglas, Abraham Lincoln and antebellum America.

Sources:

Alexander Davidson and Bernard Stuve, "A Complete History of Illinois from 1673-1884." (Springfield: H.W. Rokker, Publisher, 1884), pp. 669-670.

Circuit Court of Sangamon County, "The Great Canal Scrip Fraud; Minutes of the Proceedings and Report of Evidence in the Investigation of the Case, By the Grand Jury of Sangamon County, Ill., at the April Term of the Court of Said County, 1859." (Springfield Daily Journal Steam Press, 1859), p. 60.

The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, Vol. 1, "1850-1864. (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1925), pp. 349-355.

Joseph T. Holmes, "Quincy in 1857. Or Facts and Figures Exhibiting Its Advantages, Resources, Manufactures and Commerce." Reprint. (India: Pranava Books, 2019), p. 55.

Erika Holst, "A History of Springfield Romances: Six Love Stories to Put You in the Mood," Illinois Times, Feb. 4, 2013.

Illinois Centennial Commission, "Governors of Illinois," 1818-1918. (Springfield: Illinois Centennial Commission, 1917), p. 21.

"Illinois Scrapbook: The Governor's Mansion a Century Ago," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. (Springfield, 1955), p. 330.

John M. Lamb, "The Great Canal Scrip Fraud," The Magazine of Illinois, 16, No. 9 (Nov. 1977) pp. 32, 33.

James T. Hickey, ed., "The Reminiscences of Clara Matteson Doolittle," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. (Springfield, 1976), pp. 3, 7, 8.

Dan Monroe and Lura Lynn Ryan, "At Home with Illinois Governors: A Social History of the Illinois Executive Mansion 1855-2003." (Chicago: R.R. Donnelly, 2002), pp. 15-17.

John Moore, "Special Report of the Treasurer of Illinois in Relation to the State Indebtedness Received from Wandsworth & Sheldon [Attorneys for Joel Matteson]." Springfield, Jan. 10, 1857.

John Tillson Jr., "History of Quincy." (Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905), pp. 164, 222.