First Radio Broadcasts Heard Across City

The evolution of the electronic medium known now as “radio” took a giant stride in 1895 when Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi devised a way to send Morse-coded telegraph messages over long distances without using wires. This innovation changed how people communicated, and by the turn of the century Postal Cable Telegraph Company and Western Union of Illinois were serving the Quincy area.

The pace of life in Adams County burgeoned as “wireless telegraphy” often reduced message delivery from days to minutes. Farmers adopted it for gathering market reports and weather forecasts; sports fans for getting scores and statistics. Aside from its practical uses, wireless became a hobby for youngsters across the United States. Boys like Gorham Cottrell and Ferd Schwarzburg in Quincy not only mastered Morse code but built their own sets able to receive and send messages.

In September 1914, Rev. Father Adrian Schmitt installed Quincy’s first wireless station capable of trans-versing the nation at St. Francis Solanus College (later renamed Quincy College, then Quincy University). Schmitt began teaching this technology in the science department and the federal government granted his station the city’s first transmitting license.

Involvement in this field faltered during World War I when President Woodrow Wilson ordered wireless communication stopped to prevent enemy interception of military secrets, and for nearly three years airwaves remained silent.

After the war ended in 1918 Wilson lifted these restrictions. Canadian-born Engineer Reginald Fesenden, who did most of his work in the U. S., added the dimension of voice and music to telegraphic key sounds of dots and dashes. Soon the invention of built-in loudspeakers eliminated cradled ear receivers designed for a single listener. These features increased the popularity of what people now called “wireless telephones.”

Quincyans who owned one could hear the premier broadcast of the 1922 World Series and one year later, President Calvin Coolidge deliver the broadcast of a presidential address. Enterprising businessmen placed a wireless within an open boxcar at Front and Hampshire to broadcast to the public. The age of radio had arrived.

Bob Compton, owner of Bob’s Battery Shop in Carthage, Illinois, along with Fred Ferris and Earl Garard, built an apparatus capable of receiving and transmitting messages over a 500-mile radius. In May 1920, they installed a 50-watt radio station, WCAZ, at Carthage College. The Quincy Whig Journal financed this venture and daily broadcasts of weather, farm markets and news began.

Two years after WCAZ went on the air, Quincy Electric Supply and the Quincy Daily Herald began the Gem City’s first radio station, WCAW, broadcasting out of the Illinois Battery Company at 316 Maine. Noel Havermale erected the equipment and managed the station. The newspaper’s December 2, 1921, edition announced: “The air is filled of music, short stories and gossip, free to everyone prepared to receive it.”

The first receptions made by Quincy residents of station broadcasts created excitement and wonder. When John Schott of 1420 Kentucky heard the grand opera “Samson and Delilah” sung in an auditorium in Chicago, it not only garnered headlines but turned Schott into a sought-after authority on radio.

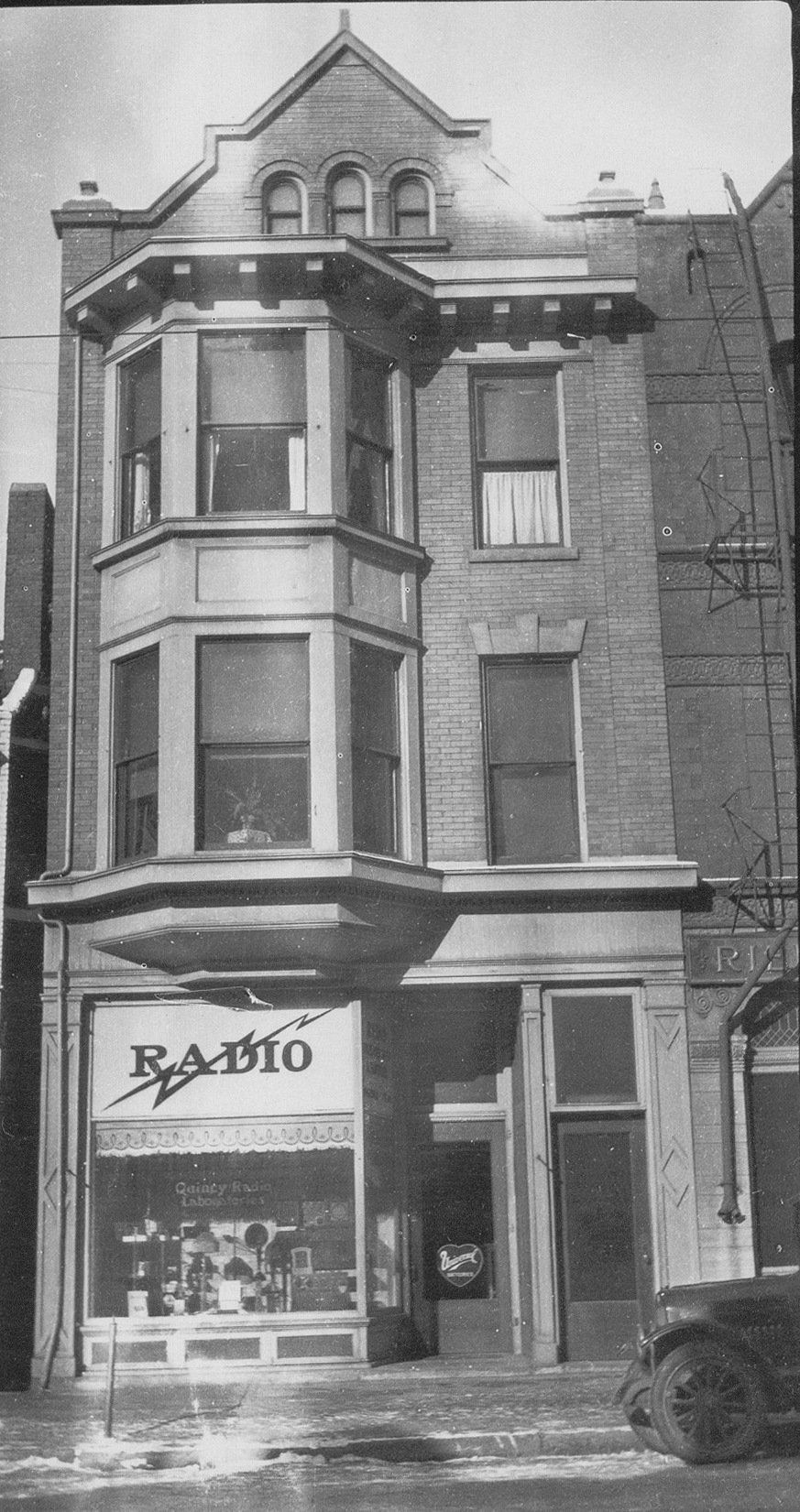

Although rising expenses soon forced WCAW to shut down, radio broadcast technology continued evolving in Quincy. Before the federal government allocated separate band width use, amateur broadcasts often interfered with station transmissions. A 20-year-old man from Hannibal, William “Bill” Lear—nicknamed by many citizens the “radio bloodhound”— usually handled complaints. He moved to Quincy in 1922 and opened Quincy Radio Laboratories at 645 Hampshire. During his two year stay in the Gem City, he not only diagnosed reception problems but wrote a technical column for the Quincy Daily Herald and built one of the world’s first compact radios. Later in his life, he became a world-famous inventor who received more than 120 patents, many related to radio.

By the mid-1920s, the city had more than two dozen shops that sold, built or repaired radios, and they formed the Quincy Radio Dealers Association. From March 10th through the 14th of 1925, this group hosted the first large-scale live local radio show, with a medley of orchestras, singing groups and entertainers performing at the National Guard Armory. Promoters selected Erwin Swindel and Miss Val McLaughlin, broadcasters from Station WOC in Davenport, Iowa, to emcee the event. Over 7,100 people listened at the Armory and at the Orpheum Theater and the Duker Furniture Company Gallery. This show became a major annual event.

Enthusiasm for this new technology sometimes fomented exaggerated claims. Russell Williams of 1805 Grove announced he could receive radio broadcasts by screwing his wireless into a light socket and creating a makeshift antenna. Quincy, he proclaimed, would soon experience the “greatest radio thrills” and be in the “very largest letters on the radio map” when it becomes headquarters of his “Super Antenna Company.” A widely-circulated but unverified belief that radio waves could hasten the growth of crops piqued the interest and then the ire of Adams County farmers.

While some predictions of radio’s possibilities vaporized in time, others accurately foretold of broadcasting’s future. An October 26, 1924 article in the Quincy Daily Journal stated: “Radio movies with voice and color will amuse audiences in the near future. Television, that mysterious device by which a person can see over a telephone wire, is the basis of this latest invention.”

A Quincy man, Chesleigh Gerard, became the first regular announcer on Bob Compton’s WCAZ station in Carthage. In July 1925, Compton changed its call sign to WTAD, telling the public these new letters stood for “ W e T ravel A ll D irections.” In December of the following year, he transferred his license and moved the station into a building at 6th and State in Quincy. By this time most homes had sets, as WTAD filled the airwaves with the sounds of radio that brought the world closer to the lives of local citizens.

Sources

“All the Thrills of Grand Opera Furnished in Your Own Home—By Wireless.” Quincy Daily Herald , Dec. 2, 1921, 11.

“Carthage Boys Show Wireless in Action.” Quincy Daily Herald , May 10, 1920, 4.

Federal Communications Commission. “History Cards for WTAD.” Accessed 28 April 2020. < www.fcc.gov >

“Get Radio in Socket of Light Globe.” Quincy Daily Herald , May 9, 1922, 14.

“Here’s Something Really New: Quincy’s First Radio Show.” Quincy Daily Herald , March 7, 1925, 6.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man . New York: The New American Library, Inc., 1964, pp 259-68.

“Quincy Now On Radio Map With Broadcasting Station.” Quincy Daily Herald , May 15, 1922, 1.

“Quincy’s First Wireless Installed at St. Francis.” Quincy Daily Whig , Sept. 8, 1914, 14.

“Radio Movies with Voice and Color to Amuse Audiences in Near Future” Quincy Daily Journal , Oct. 26, 1924, 11.

“Radio Shop Will Be Opened on Hampshire.” Quincy Daily Journal , Nov. 12, 1922, 6.

VanCour, Shawn. Making Radio: Early Radio Production and the Rise of Modern Sound Culture . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.