Floyd Dell’s Illustrious Writing Career Began in Quincy

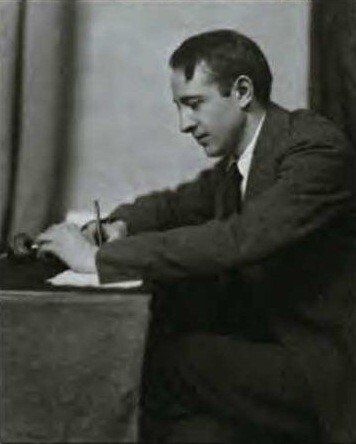

Floyd Dell was born in Barry, Illinois, in 1889 and lived in Quincy from the ages of 12 to 16. During those four years, he began writing and the themes he would explore during his prolific career emerged. Dell became a best-selling author and his novels made into four Hollywood movies and a hit Broadway play. (Photo courtesy of the author and in the public domain)

Floyd Dell’s adolescence in Quincy inspired him to become an author. He became one of the most important American writers of the first half of the 20th century, a prolific novelist, poet, playwright, critic, and editor. He resided here from 1899 to 1903, between the ages of 12 and 16, a crucial period that shaped his life and provided the themes that would illuminate his work: socialism, atheism, and free-thinking.

Although he became a best-selling author and inductee into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, and his work made into four Hollywood movies and a hit Broadway play, Dell saw himself in Quincy and for the rest of his life as an iconoclast and rebel. After leaving Quincy, he lived as a bohemian artist, first in Davenport, Iowa, then Chicago, and finally New York’s Greenwich Village, dovetailing into that avant-garde generation of the 1920s that shunned conformity but valued art and believed it could change the world.

Floyd James Dell was born on June 28, 1887, in Barry, Illinois, the youngest of four children. His father, a Union Civil War veteran and staunch abolitionist, worked as a butcher in Barry. His mother, a former teacher, maintained the household until the depression of 1893 hurled the family into dire poverty. Dell’s three older siblings soon dropped out of high school and moved to Quincy looking for factory work. In 1899 Floyd and his parents followed. The family lived in a decrepit house on the city’s south side and the Dell boy enrolled in Franklin School, at the time a junior high.

His parents doted on their youngest child and aspired for him to attend college and for the family to gain “respectability.” Katherine Dell encouraged her son to read and believed he could do better in the world than her older children. Dell did well in school but withdrew from his peers after a brief but life-changing encounter soon after arriving in Quincy.

A boy introduced himself to Dell by saying “My father is a doctor. What is yours?”

Ashamed of his family’s poverty and his father’s lack of steady work, Dell became a recluse and spent most of his time at the Free Public Library, which he called a place of “perfect equality.” At the library, he read voraciously: poetry, travel, novels, and the revolutionary works of Charles Darwin and Sigmund Freud, which had a profound influence on him.

At Franklin School, his study of Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice sparked his passion for language, and he wrote his first poem: a plea for people like his brothers to stop drinking, which Dell supposed caused the country’s destitution. The study of grammar and parts of speech suddenly became fascinating: a writer needed these skills to hone his craft. Later, while reading Edgar Alan Poe in class, he began writing stories and founded a school literary society. Upon his ninth-grade graduation in 1901, he delivered a commencement oration.

Dell’s mother sent him to the Presbyterian Church and its Sunday School, believing this would bolster his chances of entering college. At his first service, a well-dressed youth from a prosperous family ridiculed a group of Civil War veterans from the Soldier Home who were in attendance, exclaiming within earshot, “Look at the blue-bellies!” Painfully aware that his own father had fought and shed blood in that war, Dell renounced churches and dismissed the Bible as a “beautiful fable.” His reading of the Koran and Mormon Bible furthered his disdain for organized religion, and he became an atheist for the rest of his life.

Having heard about Martin Luther’s famous nailing of the ninety-five theses on the Church door at Wittenberg, Germany, Dell contemplated posting a similar proclamation of atheism at Quincy’s Presbyterian Church. In his autobiography Homecoming, Dell wrote of his turbulent adolescence, made more perplexing by his study of Freud: “What the Church, despite all its efforts to frighten us with hell fire, could not do for us in the way of taking our minds off the subject of girls’ eyes, lips and breasts, we did for ourselves by hating the Church.” Later he became one of the first champions of feminism and women’s rights.

Meanwhile his reading of Karl Marx moved Dell toward socialism. This political philosophy explained his family’s plight as the result of a system that exploited workers and created a class of poor people, who were not, as many local citizens believed, “shiftless and lazy.” During the four summers he worked in Quincy factories to help support his family, he wrote several plays, one about Benedict Arnold and another about the abolitionist John Brown.

These first major works expressed his sympathies for rebels and outcasts like himself. He wrote in his autobiography: “My life seemed now to have some meaning, to be whole. Atheism was a natural part of socialism. And I was an enemy of the established order, Church, and state both, and set out to destroy it.”

One day he met William Morris, a Quincy street-sweeper, who like himself had converted to socialism. Morris invited the audacious youth and one of his few friends from Franklin School with similar views to attend a political meeting. Although they were only fifteen, the two joined Quincy’s socialist party during an era of profound economic hardship that had left many people across the country disillusioned with capitalism.

In his semi-autobiographical novel Moon-calf, Dell portrays Quincy as “Vickley” with a mixture of alienation and affection. He never quite scorned small-town America the way Sinclair Lewis did in his satiric work Main Street, a classic novel published the same week as Moon-calf. Like his older siblings, poverty forced Floyd Dell to drop out of high school. But he had fallen in love with literature in Quincy and formed the unswerving belief that art holds the power to kindle social reform. The Gem City endured as the bittersweet town that had rebuffed him, but where his literary career began and the themes he wrote about and lived first took flight.

Sources

Clayton, Douglas. Floyd Dell: The Life and Times of an American Rebel. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1994, 3-

18.

“Creditable Work By a School Boy.” Quincy Journal, June 15, 1901, 1.

Dell, Floyd. Homecoming: An Autobiography. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1933, 42-78.

Dell, Floyd. Moon-calf: A Novel. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1920.

Gertz, Deborah. “Program Spotlights Berry Native Floyd Dell.” Quincy Herald-Whig, Jan. 29, 1996, 3A.

“Local and General News.” Quincy Daily Journal, Nov. 5, 1900, 7.