Fred Wolf: From pillar of business to convicted felon

After immigrating to the United States from Germany in 1869 at age 18 and settling in Quincy two years later, Frederick A."Fred" Wolf began living the American Dream.

He was a meatcutter for nine years before partnering with Joseph Michael and Henry Blomer in a pork packing facility; there he learned business and managerial skills.

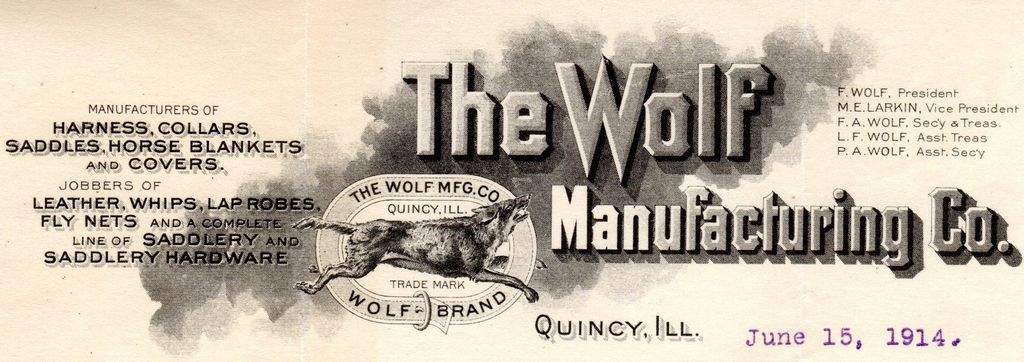

Venturing out on his own in 1889, he founded the Western Harness Co., a plant that manufactured leather products. The business at first was at 10th and Broadway and later moved to 116 N. Third. It eventually became one of Quincy's major industries, and by the beginning of World War I, employed 150 people. The company's name was changed to Wolf Manufacturing.

Fred Wolf married a native Quincy woman of German descent, Elizabeth Vandenboom, in 1879, and they had eight children. They turned Wolf Manufacturing into a family-run business: Fred as president, son Paul as secretary and Fred Jr. as treasurer.

Besides being a prominent businessman, Wolf was a devout Roman Catholic, an officer in the Quincy German Catholic Federation and a trustee of St. Mary Hospital.

Wolf became so successful and well-liked that in 1901 he ran for mayor. Although he lost his party's nomination to John A. Steinbach, who would later be elected mayor, a Quincy Daily Journal editorial praised him and his 22 years in local business.

During World War I, the U.S. government awarded Wolf 10 contracts totaling $1.8 million to produce harnesses, halters and scabbards for the war. Wolf shifted to 100 percent war work and increased his workforce to 300 employees. His plant became the city's leading war producer and one of the country's largest leather manufacturers.

In public though, and in local editorials and letters to the editor, Wolf decried American "jingoism" in foreign affairs. From the beginning of World War I in 1914, he denounced England's attacking of his German homeland and later American intervention. Before long, officials began scrutinizing him more closely, perplexed by how a native-born German opposed to the war could secure such large military contracts, and whether he was fulfilling them properly. Their suspicions proved fruitful.

On Aug. 20, 1918, federal marshals arrested Wolf and his sons Paul and Fred Jr. on conspiracy to defraud the government and placed Wolf Manufacturing under police surveillance. Prosecutors charged that Wolf had removed "rejected" stamps that inspectors placed on some of his products and shipped defective goods to soldiers -- placing American lives in danger and the war in jeopardy.

The Quincy Daily Journal on Aug. 21, 1918, now intimated treason: "The charge is one of the most serious that can be brought against any man. If true, it means robbing of the country which is fighting for the accused ... and merits the harshest possible penalty. (He) is an outcast among the right thinking people of Loyal America."

After being indicted by a grand jury, the trial of United States v. Frederick A. Wolf Sr. and Paul Wolf began Sept. 4, 1919, in Quincy's federal district court with Judge Louis Fitzhenry of Bloomington presiding. Prosecutors dropped charges against Fred Wolf Jr.

Before the trial began, Wolf fired Ed Pelgren, his chief foreman -- and several other foremen -- when he learned they might be called to testify. As reported in the court coverage of the Quincy Daily Whig on Sept. 5, 1919, Pelgren stated that Wolf had told him to remove rejection marks with acid and reassured him saying, "Now, Ed, you stand on your hind legs and stick by me and we will see this thing through."

Pelgren further testified that Wolf had said, "Tell the (expletive deleted) inspectors to go to hell. I'll make them take the straps."

Wolf also had told his employees to ship them because "They are liable to get to the bottom of the sea anyway, and nobody will know the difference."

Testimony among the 30 other witnesses included statements reported in the Sept. 10, 1919, Daily Herald that rejected and remarked that products were "So rotten that they were unfit for any service."

Mr. Nichols, a government inspector, testified that his official stamper denoting "approved" or "rejected" had been stolen, and he later discovered it in Wolf's office.

Defense attorneys Hugh Graham and Harry Converse of Springfield and George Govert of Quincy countered that anti-German hysteria and prejudice had gripped Quincy, and as recorded in the Sept. 19, 1919, Quincy Daily Whig, "Everyone saw a German spy hiding behind every tree."

With strong ties to his homeland and anti-war views, Wolf had become a victim of the government's overzealous pursuit of German-Americans.

After a two-week trial and five hours of deliberation, jurors found Frederick A. Wolf, Sr. and his son Paul guilty of felony conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government and sentenced Frederick Wolf to one year and one day in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth. Paul Wolf was sentenced to two years in the same prison.

Wolf's lawyers immediately began convoluted legal maneuvers: appeals to the circuit court, U.S. attorney general, Supreme Court and even President Warren G. Harding, but to no avail. In February 1923, nearly five years after their arrests, father and son entered prison. On Feb. 19, 1923, the Quincy Daily Herald stated they were "trembling with fear that the penal institution was like the prisons of old and expected harsh and rough treatment."

President Harding paroled Fred Wolf after he had served one-third of his sentence, and he returned to Quincy. Paul returned after eight months in prison. The now disgraced founder of Wolf Manufacturing received a passport in 1925 to spend six months in his birthplace of Gleiswceler, Germany. Shortly after his arrival back in Quincy, he died Aug. 24, 1926, and after a Requiem Mass at St. John's Catholic Church, survivors buried him in the family plot in Calvary Cemetery. None of Fred Wolf's eight pallbearers had ties with his soon-to-be-disbanded company.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer and photographer whose work has been widely published as a contributor to literary magazines, a correspondent for Catholic Times, and for the past 23 years as a writer for the Library of Congress' Veterans History Project. He is a member of the reorganized Quincy Bicycle Club and has logged more than 10,000 miles on bicycles in his life.

Sources:

"Arguments of Counsel on Closing Day of Wolf Case." Quincy Daily Whig, Sept. 19, 1919, p. 3.

"Fred Wolf and Son, Paul, Are Held For Trial." Quincy Daily Whig, Feb. 22, 1919, p. 10.

"Fred Wolf Arrested, Charged With Defrauding the Government." Quincy Daily Journal, Aug. 20, 1918, p. 13.

"Fred Wolf in Plea For Impartial View." Quincy Daily Whig, Feb. 9, 1917, p. 3.

Lock, Larry. "Quincy and Adams County During the First World War." In People's History of Quincy and "Adams County: A Sesquicentennial History," Rev Landry Genosky, O.F.M., ed. Quincy, Ill.: Jost & Kiefer Co, p. 492.

"They Will Be Sunk Anyhow." Quincy Daily Herald, Sept. 4, 1919, p. 5.

"This Is For Men Who Want." Quincy Daily Journal, Jan. 20, 1897, p. 5.

"Used Acid to Remove Marks of Rejection, Says Factory Foreman." Quincy Daily Herald, Sept. 10, 1919, p. 7.

"Witness Saw Fred Wolf, Sr. Erase Rejection Marks From Stamps Used In Army Halters." Quincy Daily Whig, Sept. 5, 1919, p. 3.

"Wolfs Disregarded the Rejections Made by Government Inspectors." Quincy Daily Whig, Sept. 4, 1919, p. 3.

"Wolfs Enter Leavenworth Penitentiary." Quincy Daily Herald, Feb. 19, 1923, p. 1.

"Wolfs Guilty." Quincy Daily Whig, Sept. 19, 1919, p. 1.

"The Wolf Scandal." Quincy Daily Journal, Aug. 21, 1918, p. 6.