Free Persons of Color and the Underground Railroad

Quincy was an ideal settlement for abolitionists on the expanding western frontier after the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Because Missouri entered the union as a slave state, this part of the Mississippi River attracted Americans who organized to defeat slavery and its expansion. As population grew so did the region’s anti-slavery network and Americans of African ancestry joined the freedom cause.

Despite state laws, the so-called Illinois Black Codes, which stripped them of their rights, free black Americans in Quincy challenged those restrictions by personally contributing to the economy, raising families and secretly confronting abusive federal laws by operating the legendary Underground Railroad.

Berryman Barnett was one of Quincy’s first known workers for the underground route. He was born in 1800 in Virginia. Barnett’s early history is sketchy, but by 1838 he had wed Esther Butler in Quincy. Their marriage license lists them as people of color.

By the 1850’s the couple and their children lived on Chestnut between Eighth and Ninth streets.

By trade Barnett was a whitewasher who sealed walls and fences with a lime mixture, a trade made famous by Mark Twain in Tom Sawyer. As a freedom fighter, Barnett is best known for his alliance with Dr. Richard Eells; scouting for escaping slaves on Quincy’s riverfront.

Eells lived atop the bluff at 415 Jersey Street, and on a summer night in 1842 Barnett guided an escaping bondsman named Charley from Monticello, Missouri to his door. Barnett apparently stayed behind while the doctor and Charley raced toward the Mission Institute campus at 24th and Maine. They were soon over taken by a posse of Missouri slave owners.

Charley was captured. Eells was later tried and convicted for harboring a fugitive slave in violation of the Illinois Criminal Code. His case was appealed, eventually being argued before the U.S. Supreme Court which upheld the original verdict. Dr. Eells died before the final Supreme Court appeal.

George Howard was a close neighbor of the Barnetts, living at the southwest corner of Eighth and Chestnut with his wife, Louisa. He was born about 1829, moved to Quincy by 1848, and is listed as a man of color in Quincy city directories.

He worked as a chemist and clerk for a pharmacy on the southwest corner of the public square, now Washington Park. His job was to mix and sell foreign and domestic elixirs, ointments, paints, oils and dyes for his boss Henry H. Hoffman. Hoffman had been a Marcelline, Illinois resident and was among the Adams County group that went to the 1837 Illinois Anti-Slavery Convention in Alton. His home, before moving to Quincy, was at the mouth of Bear Creek on the Mississippi River. A hidden space around his fireplace concealed fugitives heading north from there.

Although George Howard worked for a known anti-slavery advocate, and lived near the Barnetts, there is as yet no direct evidence that he was fighting slavery before the Civil War.

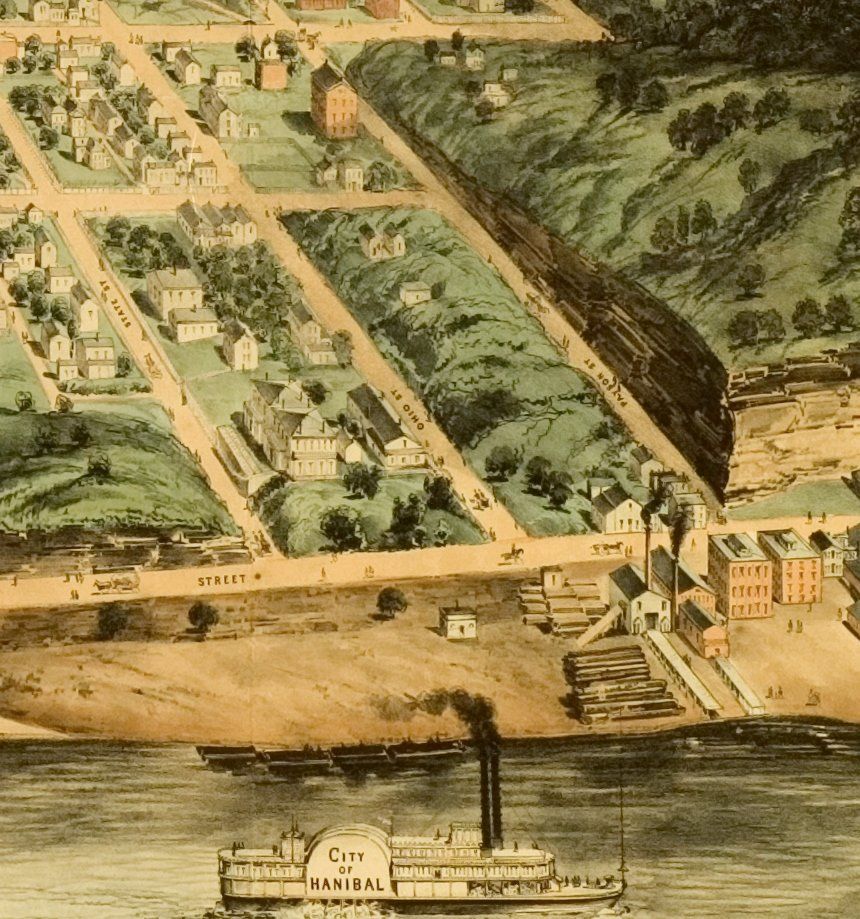

Charles Sidener moved to Quincy by 1848, and later lived on Chestnut between Ninth and Tenth Streets with his wife, Hester, and son. Sidener had been enslaved, but was freed by his Missouri owner. His skills landed him a job as a sawyer and engineer at John Van Doorn’s sawmill on the riverfront. Van Doorn, his employees, and other anti-slavery Quincyans had been perfecting a route to freedom for years, and Sidener was a key player on the first leg of the Canada trek.

In the late 1840’s, a slave named Henry Stevenson from Audrain County, Missouri passed through Quincy, on business for his owner. While here he happened to meet Sidener, and together they arranged for Stevenson’s trip to Canada that very day. When Stevenson was interviewed and photographed in Windsor, Ontario in 1892, he confirmed Sidener’s role as a conductor for his journey from Quincy to Canada.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required citizens to return runaway slaves to their masters, which further increased national tensions. Angry abolitionists nicknamed it the “bloodhound law” and free blacks living in Border States were in more danger of bounty hunters who might destroy their freedom papers and drag them back to slavery. In the years after the FSA passed, thousands of slaves made their escape to Canada, where laws prohibited the surrender of a slave.

Despite the draconian edicts of this 1850 Act, Quincy’s freedom team pressed on, as more black abolitionists moved to town in the 1850’s, including the Clark family from New Philadelphia, the nation’s first black-founded town. After their arrival in Quincy, Simeon and Monroe Clark worked for John Van Doorn and helped many runaway slaves alongside Charles Sidener. The Clarks brought valuable knowledge to Quincy’s abolition cause, as they knew Free Frank McWorter and his family intimately from their time in Kentucky. Years after emancipation, Simeon Clark recalled how he had “time and again, assisted his flying brothers from the pursuit of the negro-hunter and his bloodhounds.”

The entire Clark family lived on Third Street just above Van Doorn’s sawmill, including Free Frank’s daughter-in-law Louisa Clark McWorter. Paul Budroe, another free black man working for Van Doorn, also lived with the Clarks.

When the Civil War began in 1862, Charles Sidener joined the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry. He was listed as missing in action in the Battle of Petersburg, Virginia and is likely buried in a mass grave there.

Berryman Barnett was unable to fight, but his son William joined the 13th Regiment, U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, and survived the war to return to Quincy.

George Howard enlisted at Alton with the 3rd U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery. In 1866, his wife Louisa is listed as a widow, as George likely died during the war.

Simeon Clark fought for the 38th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry, before moving his family to Kansas in the 1870’s.

In addition to aiding men and women of color on the road to freedom, many of these dedicated local men and members of their families also served and in some cases gave their lives in the Civil War to further insure the freedom of all.

Sources

“Council Proceedings.” Quincy Daily Whig, Nov. 13, 1854.

“Grand Celebration of the Ratification of the 15th Amendment. Our Newborn Citizens in Council.” Quincy Daily Whig, April 8, 1870, 4.

Quincy City Directories 1855-1875.

Shackel, Paul A. “New Philadelphia: An Archeology of Race in the Heartland.” University of California Press, 2010.

Walker, Juliet E.K. “Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier.” University Press of Kentucky, 1982.