German-Americans and start of World War I

The assassination of the heir to the Austrian-Hungarian throne set in motion a chain of events, which embroiled Europe’s largest and most powerful nations in a war. It began in August 1914 with cheering crowds, full of patriotism, sending great armies off to war. Tremendous battles and matching casualties followed and shocked both sides. The Great War, fought mainly in Western and Eastern Europe, eventually spread worldwide. Its effects even touched a quiet river town in Middle America.

Numbering 8.2 million, or 9 percent, German-Americans in 1910 were the largest ethnic population in the United States. Adams County’s population stood at 64,558 with 36,587 people living in Quincy. Forty-three percent of Adams’s citizens were either foreign-born or of foreign extraction. Of Quincy’s foreign-born, 2,840 were from Germany. Another 6,589 Quincyans were born of German parents.

In August 1914, German-Americans in Quincy could live their lives with only a limited need of English. From corner groceries and other local businesses, to factories and workshops, German was spoken and understood. One could find church services in German, and parochial schools, whether Catholic or Protestant, used German. For its German patrons, the Quincy Public Library circulated a large collection of books in German. The primary language in many neighborhood taverns was German. The same was true for a number of social, fraternal, and athletic organizations that met in the Turnverein, a gymnastic/ fitness organization. The hall, located at 926 Hampshire, which still exists and is called Turner Halle then. In addition to the Quincy Herald, Whig, and Journal newspapers, a German language paper, the Germania, served the community.

For most Americans the conflict was far away, and more importantly, they saw the United States having no vital stake or interest in the outcome. However, the summer of 1914 found a number of Quincyans seeing the European turmoil up close and personal. For they or their immediate family were in the Fatherland visiting relatives or vacationing. Still others had family and relatives swept up by the war. Quincy newspapers reflected the anxiety that the European War brought to the community.

On Aug. 3 the Quincy Whig reported that the German counsel at St. Louis asked “all German reservists to proceed (sic) home.” The newspaper stated that “quite a few Germans are employed at the Knittle Show Case company, Huck Manufacturing company Gardner Governor works and other local factories.”

That same day Quincy’s Daily Journal grabbed its readers’ attention with an article headlined, “QUINCY MAN TO FIGHT IN GERMAN ARMY, PETER SCHLITZ LEAVES TONIGHT TO PROTECT PROPERTY IN GERMANY AND FIGHT FOR KAISER.” The newspaper noted that Schlitz who was “about 30, and an employee of the Roeder and Greenmann contractors, will board a train tonight bound for New York, from where he will sail for Germany, in order that he may take up arms with his country and protect property which he owns.” The reporter added: “Schlitz has resided here for some years, but has never relinquished his ownership to some land in Germany.” And, Schlitz told the reporter that he will be on the firing line as soon as he reaches Germany.”

The Daily Journal’s reporter added that “the war is of great interest to Quincy people because of the fact that many of them have nephews and other near relatives in the standing army. ...”

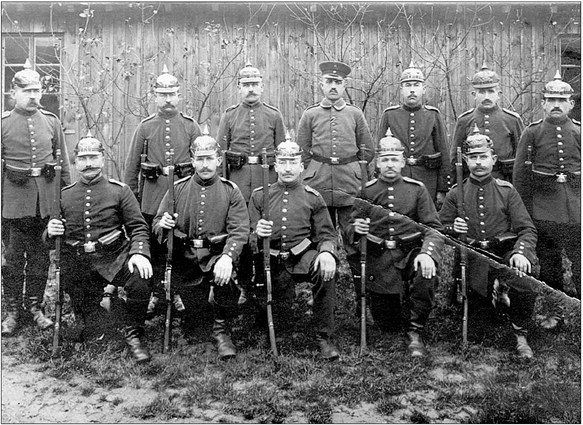

The Daily Journal on August 7 ran a story about August Bellendorf’s two sons who were in the German army. Bellendorf was an employee with the Cudahy packing plant. In 1889, he came directly to Quincy from Dorsten, Germany. Shortly after arriving, Bellendorf married, and from the union came two sons, Wilhelm and August. However, with their mother’s death, the boys were sent to live with relatives in Germany. At the war’s outbreak the boys were in the same regiment, fulfilling their two-year mandatory military service. Bellendorf told the reporter that his younger son had written saying “that they had received orders to move, although he did not know where.”

Both Dick Bonness, a baker at Thompson’s restaurant, and Herman Butzkueben, a teller at the Illinois State Bank, each had three brothers serving in the German armed forces. Bonness’ sister wrote from Berlin saying that his brothers, Robert, Otto, and Carl were fighting on the Russian front near Warsaw and that so far they had survived. On receiving a letter from his mother, Butzkueben told the Whig that one brother was in the German aviation corps, another was “in the thickest of the fight in Russian Poland,” and due to the chaos of war, the third was in a place unknown to him.

With the declarations of war in Europe, a number of Quincyans traveling, studying, or visiting family, especially Germany, struggled to return to the United States.

Miss Florence Halbach was visiting relatives at Lippstadt, Westphalia, Germany when the war broke out. She wrote her mother that “Lippstadt is on a direct line between Germany and France and often there is as many as 35,000 men stopped here in one day.” She explained: “In four days a shed and kitchen was built which can accommodate 3,000 men at one time. Last week every hour of the day and night a train came through with 1,000 to 3,000 men to be served. Clarchen and I offered our services for three nights this week. We go at 8 p.m. and stay until 6 a.m. ...” She was inspired “to see these fine young men so eager to do what they can for their fatherland. The soldiers sing and laugh just as if they were going to some grand celebration instead of a possible death.” On arriving back in Quincy, Florence told a Whig reporter “that she is enthusiastic in favor of the Germans chance for victory over the allies.”

F. Joseph Hildenbrand, a clerk at the Quincy post office, traveled in July 1914 to Freiburg, Germany, to visit relatives. In Heidelberg, he met with Mrs. Helen M. Seaman, a former Quincy resident and a Whig subscriber. The Whig reported that Mrs. Seaman “has taken quite an interest in setting the people of this city right as to the real situation in her Fatherland.” The paper explained that Mrs. Seaman “was much afraid they (American newspapers) were not giving the German side.” As a consequence, she convinced Hildenbrand to bring three copies of the German “White Book” back to the United States. One copy was specifically for the Whig. The “White Book” set out Germany’s reasons for declaring war against Russia, and how this decision led to the greater European War.

The Whig noted that few “White Books” had “reached this side of the water thus far, because of difficulty in bringing them through the customs offices in England. Mr. Hildenbrand was luckily, not searched, and was able to carry copies through. ...” Hildenbrand commented: “’I was very nervous ... all of the time I was in the custom house.’” Regarding the “White Book,” the Whig editors wrote that they believed “in publishing this fair explanation of the German side of the questions. Too long have the American newspaper readers been forced to depend upon news matters from sources inimical to the kaiser’s cause and the German readers of The Whig, who number legion, are requested to take into consideration the desire of this paper to print a fair statement of their cause. ...”

Wars are not just fought with bullets and bombs. Germany’s attack on neutral Belgium opened the door for a British propaganda campaign, emphasizing atrocities that later were exposed to be outright lies or exaggerations —- proving the axiom that “in war, truth is the first casualty.” The sinking of the RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915, with the loss of 128 Americans, began the slide of public opinion away from Germany. Further sealing Germany’s fate was the fact that Great Britain and France borrowed heavily from New York banks to finance the war. United States neutrality went out the door with the first Allied loan.

Phil Reyburn is a retired field representative for the Social Security Administration. He authored “Clear the Track: A History of the Eighty-ninth Illinois Volunteer Infantry, The Railroad Regiment” and co-edited “Jottings from Dixie: The Civil War Dispatches of Sergeant Major Stephen F. Fleharty, U.S.A.”