Governor got undeserved credit for Civil War skirmish

It was, as a writer described its appearance before 1850, "a pathless sea of grass ... a few small farms in the edges of the timber ... no improvement visible in any direction."

This was "the Mound," a landmark for the smattering of settlers who had migrated into the area around where Monroe City, Mo., is today.

It was on this once peaceful plain that Quincy founder John Wood, recently appointed quartermaster general of Illinois, would gain national attention and credit for rescuing 500 trapped Union soldiers under siege in Monroe City at the beginning of the Civil War.

In the mid-19th century, winds of expansion whirled through the grassy prairie at the Mound. Surveys were made, immigrants came, farms encroached and rails were soon laid. In 1852, the first right of way was acquired for the Hannibal-St. Joseph Railroad on the open land near the Salt and North rivers, which drained part of the watershed in Northeast Missouri into the Mississippi River.

In 1856 plans for an intrastate railroad were completed in the Hannibal office of John M. Clemens, father of Samuel (Mark Twain). The first track was laid in Monroe County in 1857. E.B. Talcott and John Dunn had formed a partnership to build the track, and Talcott would use some closely held information to build his wealth. Knowing where stations would be needed along the railroad line, Talcott bought a half-section -- 320 acres -- of land and laid out the town of Monroe Station.

To market his town, Talcott sponsored a picnic and public sale of lots. In time, a business district formed, and small homes clustered in neighborhoods. Talcott himself built a hotel. S.F. Hawkins established a general store. Investors created a livestock market for breeds of horses raised on bluegrass that immigrants from Kentucky and Tennessee planted on the surrounding prairie.

Before he left his Monroe Station project after 1857, Talcott appointed John L. Lathrop a trustee with authority to sell lots in the town. At Talcott's direction, Lathrop transferred a 7.5-acre property to a group of local farmers and businessmen to establish a school, the Monroe Institute. The Legislature chartered the school, and area settlers raised $10,000 to build a large, two-story brick building. In the summer of 1860, the building was finished. Wrapped on two sides by a wide veranda, it opened that fall with 24 classrooms. George Philander Cummings, a minister educated at Dartmouth College, and his brother S.E. Cummings, were the first principals. It was in the Monroe Institute on July 10, 1861, that Col. Robert Smith from Hamilton and some

500 Union troops of his 16th Illinois Infantry of Quincy were trapped by a rebel force nearly four times the size of Smith's. The colonel's regiment was one of six organized under Illinois Gov. Richard Yates' order of April 16, 1861 -- four days after Confederates bombarded the Union's Fort Sumter in the harbor at Charleston, S.C. Capt. T.G. Pitcher, a West Point graduate from Indiana, mustered in men on May 24, 1861, at Quincy's Camp 1. Soon renamed Camp Wood to honor Gov. Wood, the camp was east of Woodland Cemetery on the south side of Adams Street between Sixth and Seventh streets.

Although they only were in their seventh week of training for their three-year enlistments, the men of the 16th had impressed Quincy spectators by their drill and appearance. The Quincy Daily Whig reported on June 15, 1861, that "the men drill six hours and the officers twice each day. All are improving very fast, and with the determination to have this regiment among the best in the State." On the other side of the Mississippi River, however, resentment over the recruiting and training of federal troops in Quincy was growing.

Responding to threats of destruction of the Hannibal-St. Joseph Railroad, Col. Smith and five companies of the 16th were dispatched to Hannibal in mid-June. The Hannibal newspaper groaned that "this abolition army from Illinois ... paraded ostentatiously on the levee at the foot of Hill street, marched with drums beating and colors flying to South Hannibal." The editor's commentary dripped with anger: "Oh, God of Justice and Right, how long are these things to continue?"

After a fruitless march southwest toward Florida on Monday, July 8, and having heard rumors of trouble at Monroe Station, Smith turned his men northward the next morning. As they approached the town on July 10, they saw smoke hanging over the horizon. A 100-man rebel cavalry led by Capt. John L. Owen of Marion County had burned the Monroe railroad station, six coaches, 18 freight cars and heavily damaged track on either side of town.

Underestimating local sympathy for the Confederate cause, Smith's force entered Monroe, where as many as 1,000 rebel sympathizers gathered around. Smith ordered his men into the Monroe Institute building and sent a messenger for reinforcements. While the number of Confederate soldiers grew, Smith had his men build earthen breastworks around the school. The fortifications and the brick school building would neutralize the effects of rebel rifle and cannon fire, which started the next day. Held off by Union retorts, rebel cannon were never closer than three-fourths of a mile. Only three cannon balls hit the building.

On the afternoon of July 11, Maj. Samuel Hayes of Pittsfield arrived with three companies of the 16th Illinois. By this time, the rebels had begun to move out. The next morning, Col. John M. Palmer's 14th Illinois arrived from Jacksonville, stayed for two days, and left Smith in what he considered "a worse position than ever, with the exception that we have more ammunition."

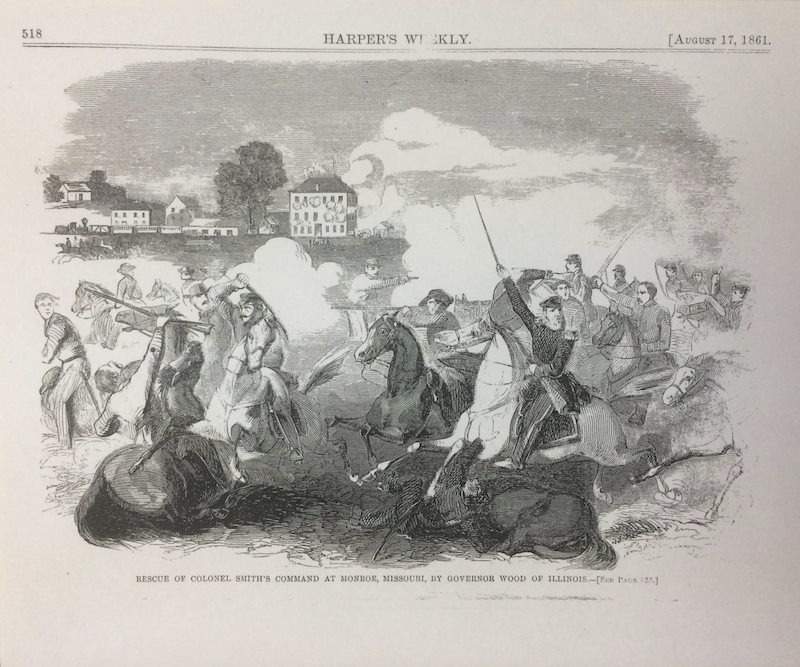

Of the reinforcements, it was only Gov. Wood who received national attention for the rescue of Smith and his five companies of the 16th Illinois. Harper's Weekly, a national magazine, printed a large illustration of Wood leading the cavalry in the routing of the rebels at Monroe. The credit was entirely undeserved. Although Wood led Companies F and H of the 16th Illinois to Monroe, the force arrived three days after the skirmish ended.

Reg Ankrom is a former executive director of the Historical Society and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources:

Emily M. Bradford, "During the War," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Springfield: Illinois State Journal, State Printers, 1915.

Albert Oren Cummings, Cummings Genealogy. Montpelier, Vt.: Argus and Patriot Printing House, 1904.

"Camp Matters," Quincy Daily Whig. June 15, 1861.

"John Marshall Clemens," aten.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Marshall_Clemens

Federal Writers Project, the WPA Guide to Missouri. San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2014.

"The Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad," at abandonedrailroads.com/hannibal_and_st_joseph_railroad.

History of Marion County Missouri, Vol 2. St. Louis: E.F. Perkins, 1884.

"16th Illinois Infantry,"Illinois Adjutant General's Report: Regimental and Unit Histories, Containing Histories for the Years 1861-1866. Springfield: Baker, Bailhache and Co. 1867.

"The Late Skirmish at Monroe City," Quincy Daily Herald. July 16, 1861.

Letter from R. Haney to Macomb Eagle, "The Fight in Missouri," July 12, 1861.

"Monroe Institute: Scene of Civil War Battle, Monroe City, Missouri," atrootsweb.ancestry.com/~momonroe/monroeins.htm.

"Monroe Township," History of Monroe and Shelby Counties, Mo. Vol 2. St. Louis: National Historical Company, 1884.

"Queen of the Prairie," atmonroecitymo.org/history_2/.

"Report of Colonel Robert F. Smith, Sixteenth Illinois Infantry, Monroe Station, Mo., July 14, 1861," Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois. Springfield, Illinois: Phillips Bros, State Printers, 1900.

"Rescue of Colonel Smith's Command at Monroe, Missouri, by Governor Wood of Illinois," Harper's Weekly. August 17, 1861.