Gutsy Jennie Hodgers:

' ... the country needed men, and I wanted excitement'

Women during the course of the Civil War often provided war-related labor in support of enlisted soldiers. As members of soldiers' aid societies women sewed, knitted, raised funds, and gathered food and medical supplies. This work did not conflict with the existing domestic confines of the "woman's sphere."

In direct contrast, several hundred women did just the opposite and enlisted with the troops to serve as soldiers. The only woman to serve as a soldier in the Civil War without having her gender discovered has a direct connection to Quincy. One hundred years ago her unusual story was widely chronicled.

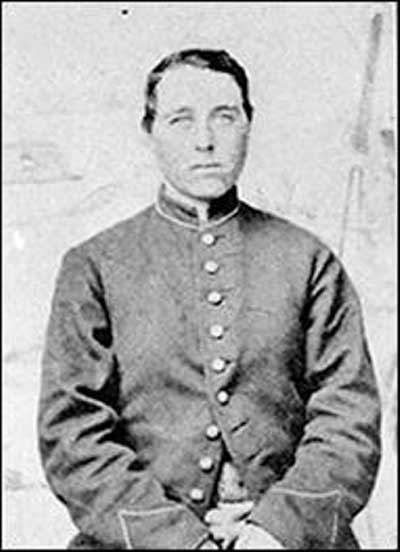

Nineteen-year-old Jennie Hodgers was mustered in at Belvidere, Ill., just east of Rockford, as Albert D.J. Cashier, private first class, Co. G, 95th Illinois Infantry on Aug. 6, 1862. Dressed in men's clothing, Hodgers began her life as a soldier. The Company Descriptive Book of the 95th shows the entry for Cashier, a 5-foot-3-inch soldier with blue eyes and auburn hair, weighing 110 pounds. Official records indicate her uncommon valor did not fit the mid-nineteenth century portrayal of women as frail and passive.

Historically significant is the fact that Hodgers was the only woman to complete a tour of duty, to be mustered out with her regiment, and receive a Civil War pension. It was no small feat! Historians estimate some 400 women enlisted. Most were discovered and discharged. Proof of identity was not needed; a woman simply picked a male name and finessed a pre-induction medical exam. Most did so to accompany their men or for adventure or financial reasons. Economic factors may have been a tangible enticement for Hodgers. A day before she enlisted, the Belvidere newspaper reported that the Boone County board of supervisors voted a $60 bounty for each recruit.

After training at Camp Fuller in Rockford, the regiment of 983 soldiers left for Cairo, Ill., on Nov. 4, 1862, and then went to Camp Jackson in St. Louis. The regiment would go on to serve in the western theater of the war and in the fight for the Mississippi. They were at the siege of Vicksburg, the Red River Expedition, and the Nashville and Mobile campaigns. The regiment's function was primarily to capture the approaches to the Mississippi River.

The Battle of Vicksburg began 150 years ago this month and lasted until July of 1863. This was one of the most crucial engagements during Cashier's enlistment. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant commanded the armies at Vicksburg where gaining control of the Mississippi was critical. The 95th was soon in the midst of the assault on Vicksburg's perimeter. The first frontal attack on May 19th and the second frontal attack on May 22nd were devastating to the regiment.

Cashier was considered a hero in connection with the first attack, as related by Sgt. Charles Ives of the 95th. As the Confederate soldiers began to retreat toward the fort, Cashier ran to the front, mounted the trunk of a tree, and waved her hat and yelled, "Come on, all you d_____ rebels, so we can see you and get a shot at you." Cashier demonstrated another gutsy occurrence when the rebels tried to take her prisoner. According to a 1913 newspaper account, Cashier was captured while on a skirmishing expedition but "seized a gun from the guard," knocked him down, and fled back to camp. After 47 days of unforgiving circumstances in sultry bayou country, the Union occupied Vicksburg. The Illinois monument at Vicksburg lists the name of Albert Cashier.

After three years of service, Albert Cashier had become a seasoned soldier of 40 battles and skirmishes and 9,960 miles of travel … 1,800 of that on foot. The 95th Illinois was mustered out on Aug. 17, 1865, in Springfield and arrived in Belvidere on Aug. 22. The depositions filed with the United States Bureau of Pensions show that the true sexual identity of Albert Cashier was never suspected by comrades.

Cashier made the transition to civilian life without changing gender identity and first became a nurseryman in Belvidere. Around 1869 Cashier moved to Saunemin, Ill., 100 miles southwest of Chicago and lived there most of her life. She first found employment on the Chesebro farm, later at Cording's Hardware Store. Eventually, Joshua Chesebro bought a lot and built a tiny house for Albert, where she kept primarily to herself and worked various jobs. Displayed among her sparse belongings was a shaving mug and brush. There was one thing that Cashier was able to do as a man that she could not do as a woman: she could vote. Saunemin residents recalled Cashier casting many ballots.

In 1910 when Cashier became ill, her long-hidden gender identity was discovered. A neighbor, Mrs. P.H. Lannon, sent her nurse when she heard of Cashier's illness. The nurse came running back to the Lannon house and yelled, "My Lord, Mrs. Lannon, he's a full-fledged woman!" From an interview with Mrs. Lannon it is known that she did not tell anyone. That same year, however, Cashier was working as a chauffeur for state Sen. Ira M. Lish and broke her leg in an accident. When the doctor set the fracture, he realized that Cashier was a woman. The injury incapacitated the veteran who was in her late 60s. She also was in weakened mental health, and the doctor and Sen. Lish decided to have Cashier admitted to the Soldiers' and Sailors' Home in Quincy, Ill. An honorable discharge from the army was sufficient to be a resident. She was admitted April 29, 1911.

The superintendent of the Soldiers' Home, Col. J.O. Anderson, was asked to keep Cashier's gender confidential. Anderson gave Cashier more private accommodations but treated Cashier as any other resident. Nurses were also sworn to secrecy. Cashier enjoyed the company of the other veterans and is said to have delighted in recounting the activities of the 95th Illinois. After about a year, other physicians were consulted when Cashier was very ill. Again, her gender was not made public.

In February of 1913 Cashier was too senile to be cared for at the home. An order of application to "Try the Question of Insanity" had been filed a week earlier, and on Feb. 26th two doctors concluded Cashier was insane. The Pension Bureau also started an investigation in March as part of a request for a raise in pension. At this point Cashier's gender identity must have been revealed to the federal government. Rumors started, and by this time newspaper reporters had heard the suspicions of a woman who had been a soldier and tried to obtain information from Col. Anderson.

Soon the story broke! Page one headlines on May 4, 1913, of the Quincy Whig made the announcement, "WOMAN MASKED AS MAN FOUGHT IN CIVIL WAR: Identify of Sex of Albert D.J. Cashier, Now an Inmate of Quincy Soldiers' and Sailors' Home Has Been Revealed by Superintendent Anderson." Leroy Scott, a fellow veteran who gained Cashier's confidence, attempted to uncover her real name. Two weeks later the May 18th Quincy Whig headline stated, "CASHIER'S NAME MAY BE HODGES." The story ran in numerous papers and continued into the spring. Some of the uncertainty in knowing Cashier's identity evolves from the fact that she told various versions of her life.

On March 27, 1914, the Adams County Clerk issued a warrant for the commitment of Cashier to the Watertown State Hospital in East Moline, Ill. There she lived in the women's ward, forced to wear a dress for the first time in over 50 years. It was reported that the patient would pin a skirt together to make pants. A statement toward the close of her life may indicate the motivation in choosing to enlist, "Lots of boys enlisted under the wrong name. So did I. The country needed men, and I wanted excitement."

Jennie Hodgers/Albert Cashier died on Oct. 10, 1915, at the age of 71. Albert D.J. Cashier was given a military funeral with burial in Saunemin at Sunnyslope Cemetery. Cashier, who had always been a member of the Grand Army of the Republic, was buried in her uniform. The tombstone is simply inscribed "Albert D.J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf."

Iris Nelson is senior research librarian and archivist at Quincy Public Library, a civic volunteer, and member of the Lincoln-Douglas Debate Interpretive Center Advisory Board and other historical organizations. She is a local historian and author.

Sources

"CASHIER'S NAME MAY BE HODGES." Quincy Whig. May 18, 1913.

Clausius, Gerhard P. "The Little Soldier of the 95th: Albert D.J. Cashier." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 51, Spring-Winter, 1958.

Lannon, Mary Catherine. "Albert D.J. Cashier and the Ninety-Fifth Illinois Infantry (1844-1915)." Master's thesis, Illinois State University, 1969.

Leonard, Elizabeth D. All the Daring of the Soldier. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999.

United States Bureau of Pensions, Civil War Pension file for Albert D. J. Cashier.

"WOMAN MASKED AS MAN FOUGHT IN CIVIL WAR: Identify of Sex of Albert D. J. Cashier, Now an Inmate of Quincy Soldiers' and Sailors' Home Has Been Revealed by Superintendent Anderson." Quincy Whig. May 4, 1913.