How generals were made, unmade during Civil War

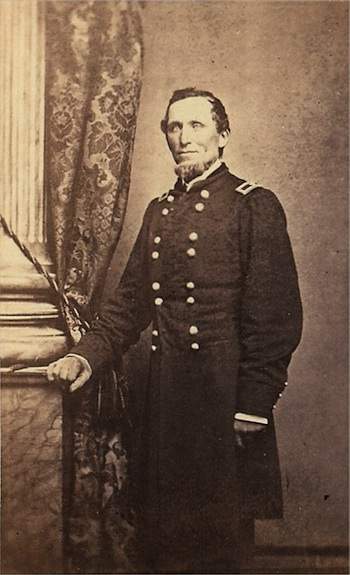

Benjamin Mayberry Prentiss could trace his family lineage back to the Mayflower. The Virginia-born Prentiss moved to Illinois in 1841 at age 21. He received some military experience as a militia lieutenant in Illinois’ Mormon “troubles” of 1844-1845.

In the Mexican War he served as a captain of the First Illinois Volunteers that earned distinction at the battle of Buena Vista. After the war, Prentiss returned to Quincy to study law. In 1860 he made his one flirtation with politics by running for Congress. William A. Richardson, another Quincyan, soundly defeated him.

Of note, Stephen A. Douglas carried the same district over Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election.

When the Civil War erupted in April 1861, Prentiss was a colonel in the Illinois militia and was given command of seven companies at Cairo at the extreme southern end of the state. In late April his men seized rebel munitions aboard river steamers, an indication of his aggressiveness. It was done four days before the War Department authorized such confiscations.

While Prentiss was in command at Cairo, Ulysses S. Grant was a mustering officer in Springfield. In August both were named brigadier generals, their commissions predated to May 17.

When Grant moved to Cairo, he gave orders to Prentiss, who balked, claiming that he was the senior officer. Grant announced that by law, because of his former rank in the U.S. service, he was the superior officer. Prentiss demurred before leaving for St. Louis to seek another command. He subsequently was commissioned to oversee northern Missouri above the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad.

In his memoirs, Grant lamented Prentiss’s decision to leave his command. Grant wrote: “General Prentiss made a great mistake ... When I came to know him better, I regretted it much ... He would have been next to myself in rank in the district of southeast Missouri ... He was a brave and very earnest soldier. No man in the service was more sincere in the cause for which we were battling; none more ready to make sacrifices or risk life on it.”

Grant’s faith in Prentiss showed up in the dramatic events of April 1862 in Tennessee. The high point of Prentiss’s service came as he commanded the 6th Division of Grant’s Army of Tennessee at the battle of Shiloh. Union troops encamped near Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., were surprised by a rebel assault under the command of Gen. Albert Sydney Johnston. Prentiss’s troops managed to hold off the rebels for about six hours. Prentiss’s position was overrun and he was compelled to surrender. Nevertheless, some historians contend that Prentiss and his troops bought valuable time with their brave defense, which helped the Union forces on the second and third days turn the tables on the rebels at Shiloh, producing an important victory.

Prentiss was held in Confederate prisons until October 1862, when he was exchanged. He was rewarded for his service with a promotion to Major General, reassigned to Grant’s command and detailed to oversee the defense of the eastern district of Arkansas.

In early July 1863, news arrived in Quincy that Prentiss’s troops had been attacked at Helena, Ark., by troops commanded by Confederate Gen. Sterling Price, a former Missouri governor. The Quincy Daily Herald published Prentiss’s account of the battle. Prentiss had anticipated an attack and established formidable defenses, placing four batteries of artillery on heights overlooking invasion routes. Trees were felled to block roads. The outcome was an impressive victory. Prentiss’s forces were outnumbered by approximately 6,500 to 4,000. Ironically, his victory was overshadowed by the huge Union successes at Gettysburg and Vicksburg at about the same time. The action at Helena, also ironically, constituted Prentiss’s final combat action.

On July 17, less than two weeks after his notable victory, Prentiss returned to Quincy and was feted in a reception hosted by the activist women’s organization, the Needle Pickets. Prentiss sought a new command but none was forthcoming. In October 1863 he resigned from the army on grounds of health and family responsibilities. In fact, he was perturbed at being passed over for command. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut, a self-promoting officer and a fellow division commander at Shiloh, notified Generalin- Chief Henry Wager Halleck that he disapproved of any position for Prentiss. Thus a “hero” of the battles of Shiloh and Helena spent the last 18 months of the war at home.

The Prentiss story reveals more about Civil War leadership than immediately meets the eye. Early in the war the huge expansion of the military required a hurried search for leaders. Prentiss had served in the Mexican-American War and had run for political office and thus appeared to fill the need. He acquitted himself well at Cairo, Shiloh and Helena, but now authorities determined that other officers better fit their plans for the remainder of the war.

By the latter half of 1863 the sorting process had worked itself out and the Union army consigned Prentiss to the sidelines.

Prentiss practiced law in his return to civilian life. When Ulysses S. Grant became president in March 1869, he had a place for his old comrade, in April naming him pension agent. He served in this capacity for eight years. In 1881, Prentiss moved to Bethany, Mo., where he served as general agent for the federal land office. In 1888, President Benjamin Harrison named him postmaster of Bethany and he was reappointed by President William McKinley. The government he had served had taken care of him with three separate patronage appointments. Prentiss died in 1901 at the age of 81.

Was Benjamin Mayberry Prentiss a politician who became a general? The answer must be a qualified one.

In the military situation brought on by the Civil War, there was need to expand from about 16,000 troops to more than one million. Where were the officers to come from for this huge expansion? Because of his previous experience, Prentiss seemed a logical choice for command and acquitted himself quite well. Later in the war he was deemed of lesser competence and was deprived of additional commands. Whether this was a legitimate judgment is debatable. As a Republican politician he had advantages in receiving a significant command. His partisan posture likewise aided him in the postwar picture.

Did the system work in Prentiss’s case? It can be concluded that a jerry-built structure worked tolerably well, and Prentiss acquitted himself in ways that brought credit to himself and to his community.

David Costigan is professor emeritus of history at Quincy University. He held the Aaron M. Pembleton Chair of History at Quincy University. He is a member of the advisory board of the Lincoln-Douglas Debate Interpretive Center.

Sources:

Costigan, David. "A City in Wartime: Quincy, Illinois in the Civil War." PhD dissertation, Illinois State University, 1994.

Long, E.B., ed. Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. New York: World Publishing Co. 1952.

Quincy Daily Herald, passim.

Quincy Daily Whig and Republican, passim

Warner, Ezra J. General in Blue. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964.