James Frazier Jaquess a Quincyan to remember

The Once Upon A Time in Quincy columns have celebrated many figures that have made a significant impact on local, state, and national history. Names like John Wood, Orville Browning, and Sarah Denman, are just a few of the many that have graced these columns. Many receive recognition in the 18 waysides that line our streets.

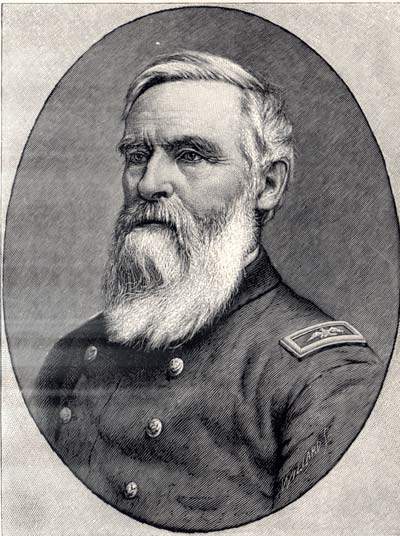

One name has seemed to slip under the radar and in many ways this person, James Frazier Jaquess, may have played the most prominent role of all. His story is told in a new book by Patricia B. Burnette titled "James F. Jaquess: Scholar, Soldier, and Special Agent for President Lincoln." Dr. Burnette has combed multiple archives to present the intriguing story of this one-time Quincy citizen. Jaquess, (pronounced Jay-kwiss) served as president of two colleges, and certainly deserves the attention of historians. Jaquess presided as commanding officer of the 73rd Illinois Infantry Regiment and operated as an unofficial emissary for President Lincoln for more than a year during the Civil War. His biography is fascinating.

James Frazier Jaquess was born Nov. 18, 1819, in southern Indiana. He enrolled at Asbury College (now DePauw University). After graduating from Asbury, he went on to receive a master's and a doctor of divinity degree from McKendree College in Illinois. As a Methodist Episcopal minister he was a circuit-riding preacher in southern Illinois. In 1849 he was named the first president of the Illinois Female College (subsequently MacMurray) in Jacksonville. He served with distinction for six years.

In 1856 Jaquess was recruited to be the first president of the Methodist German and English College in Quincy. He was the esteemed leader of the co-ed institution located at Third and Spring streets. The school closed when its impressive building was taken over by the federal government in 1863 for use as Military Hospital No. 4 for Union soldiers.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, Jaquess spoke ardently that the war should be not only for restoration of the Union, but also for the end of slavery. He had long been a vigorous opponent of slavery. His abolitionist bent made him a controversial figure to conservative Quincyans. His commitment to the cause led him to resign as college president to enlist as chaplain of the 6th Illinois Cavalry in August 1861. The regiment's main activity was combating guerrilla elements along the Missouri and Kentucky borders.

Dissatisfied with being confined to a chaplain's duties, Jaquess sought and received permission from Illinois Gov. Richard Yates to form a new regiment. The 73rd Illinois Infantry was mustered into the service at Springfield on Aug. 21, 1862, with Col. James Jaquess as commanding officer.

The regiment included 12 clergymen and many enlisted men were members of the Methodist Episcopal Church. This fact resulted in the unit being called, "the Preacher's Regiment." The regiment saw its first combat action at the battle of Perryville, Ky., on Oct. 8, 1862. The bloody, but indecisive battle, temporarily damaged Jaquess's reputation. He interpreted his orders to move his troops away from the line they held. A Court of Inquiry exonerated him and he retained his command. The next major combat for the 73rd was at the battle of Stone's River, Tennessee, but Jaquess was absent from his unit at that time. He was back in command for the bloody battle of Chickamauga, Tenn., on Sept. 20, 1863. The unit suffered a heavy toll of 23 killed, 17 wounded, and 31 captured in the battle, a searing defeat for Union forces commanded by Gen. William S. Rosecrans.

When absent from the 73rd it was not for frivolous reasons. In the summer of 1863 Jaquess suggested that there must be some solution to the war's fundamental issues as it was appalling how "Christians were killing Christians" in such huge numbers. Lincoln approved an "unofficial" mission to the Confederacy. Jaquess was received in Petersburg, Va., and apparently there was agreement to the colonel's basic tenet as he met with rebel officers and southern religious leaders, but no recognizable solution was apparent.

In 1864 Jaquess conceived of yet another "peace mission." He went to Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, accompanied by New York journalist, Richard R. Gilmore. The unofficial diplomats met with President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of State, Judah P. Benjamin on July 16, 1864.

The message they took from Lincoln signaled to the Confederate leaders that peace and reunion could be arranged with these stipulations: emancipation must stand, but with compensation to slave owners, and with amnesty afforded to all rebels. Davis bristled at the mention of amnesty, insisting they were not criminals in fighting for the right of the consent of the governed. Davis put it this way, "We are fighting for independence, and that, or extermination we will have." Davis' words were widely quoted in northern papers. Jaquess then reported directly to Lincoln.

According to subsequent accounts, Lincoln heard what he expected and wanted to hear. Davis' words contradicted the appeal being made by peace Democrats that a negotiated settlement and reunion were possible. The popularity of the widespread peace appeal had caused Lincoln to assume he would not be reelected in 1864. However, the wide dissemination of the facts of the Jaquess-Gilmore diplomacy put a new light on the election.

The mission clarified that there was no negotiable middle ground. Historians James McPherson and John Waugh recognize the Jaquess-Gilmore mission as providing powerful clarification of what the Democrat platform of reconciliation would actually mean. Quincyan James Jaquess' contribution to Lincoln's reelection cannot be ignored. The reelection of Lincoln was the final great turning point of the war, for it indicated that the war would be fought to an ultimate conclusion, with both reunion and the end of slavery as the result.

Before the war's end Col. Jaquess made another trip to his home town to preside over the wedding of his daughter, Margaret, to Henry A. Castle, a Quincy attorney, and an officer with the Preacher's regiment. The marriage took place on April 18, 1865, just three days after the death of the slain president. One can only imagine that the day was a combination of joy and sadness.

The final scene for the Jaquess peace mission came in Congress in 1870. Jaquess petitioned that his mission had never been reimbursed. He acknowledged that his first mission had been paid for by the president himself, but on the second he relied on his own funds. The Committee on Military Affairs concluded that Jaquess' request was legitimate and authorized the full amount of $6,719. This was authorized in Senate Bill 886 and the amount was finally paid on Feb. 12, 1873, the 64th anniversary of Lincoln's birth. This was a final testimonial to the importance of the mission he undertook for the president.

The post-war years saw adventures and misadventures in the Jaquess story. It seems that troubles and difficulties far outweighed the positives. One thing appeared to be a constant, and that was the respect and admiration Jaquess inspired in the men of the 73rd Illinois regiment. Jaquess died at St. Paul, Minn., on June 16, 1898.

There is much more to the Jaquess story, but that is best told in "James F. Jaquess Scholar, Soldier and Private Agent for President Lincoln" by Patricia B. Burnette, published in 2013.

Professor Emeritus David Costigan held the position of the Aaron M. Pembleton endowed chair of history at Quincy University .