John Wood and the Peace Conference of 1861

On Jan. 7, 1861, Virginia Gov. John Letcher proposed that delegates from every state gather in Washington in February for a national conference to stop what he called a "monstrous" march toward disunion "merely because men cannot agree about a domestic institution." The institution was slavery.

Illinois Gov. John Wood, whose 10-month term would end one week after Letcher's plea, knew there was no chance that disunion could be averted. The presidential election of 1856 had foreshadowed the coming division. That election shocked the South -- and provided the lesson that elected a dark horse presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln, in 1860. Here's how it happened.

John C. Fremont, who in 1856 was the two-year-old Republican Party's first presidential candidate, had nearly been elected on a platform to stop the spread of slavery. Had he won Pennsylvania, which went to favorite son James Buchanan, and either Illinois or Indiana, Fremont instead of Buchanan would have been the 15th president of the United States. And he would have achieved the victory without a single electoral vote from the South.

Fremont's near-miss showed Republicans that a free-soil ideology could win the presidency in the North alone. That became the Lincoln campaign committee's successful strategy for 1860. The South recognized the threat.

Ten southern states did not even include Lincoln's name on the ballot. The lesson of the 1856 election for the South was that they no longer had the iron grip they had exerted on the central government for most of seven decades. Foreseeing no satisfactory way ahead to protect slavery, Southern "Fireaters," pro-slavery extremists, began planning secession.

By Feb. 4, 1861, when the Washington Peace Conference convened, disunion was well underway. South Carolina, a perennial proponent of secession, had departed on Dec. 20, 1860. Mississippi left on Jan. 9, 1861. By Feb. 1, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas joined in breaking their bonds with the Union.

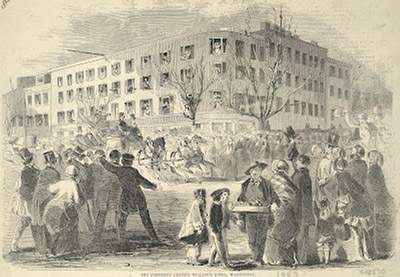

A full month before Lincoln was inaugurated president, the Confederate Congress on Feb. 4, 1861, convened its first meeting in Montgomery, Ala. On the same day former President John Tyler of Virginia, a slave owner who was elected the peace convention's chairman, gaveled to order the 132 delegates from 21 states.

If there were those who thought the Deep South could be enticed to return to the union, Quincy's John Wood was not among them.

Republican Richard Yates of Jacksonville, who succeeded Wood as Illinois governor on Jan. 14, appointed his predecessor one of five Illinois delegates to the peace convention. Other delegates were Ottawa lawyer Burton C. Cook, Lincoln's second law partner Stephen T. Logan, anti-Nebraska Democrat John M. Palmer, and Freeport Mayor Thomas J. Turner. According to Robert Gray Gunderson, who chronicled the convention, radicals in Congress -- men who would accept nothing less than an end to slavery -- applauded Wood's appointment.

In Washington, Wood took little interest in the convention. Believing Illinois' delegates would signal Lincoln's views, other states' representatives looked to the Illinois delegation for clues to Lincoln's thinking. Wood and the delegation provided little. That reflected Lincoln's attitude toward the convention. He saw nothing that could come from it. As he said in more than a dozen private and confidential letters in December 1860, President-elect Lincoln admonished powerful friends, north and south:

"Let there be no compromise on the question of extending slavery. If there be, all our labor is lost. ... The tug has to come, and better now, than any time hereafter."

Lincoln did not waver from that position, although he made no remarks about it during the convention.

Wood's main contribution during the peace convention came when he learned that New York financiers had threatened to stop the flow of money to Lincoln's administration unless some compromise was achieved with the South. New York bankers and brokers were largely dependent on revenues that southern cotton brought them. Wood, along with Palmer and Cook, in a message to Yates urged that Illinois guarantee a proportionate share of loans to the federal government to weaken the New York financiers' influence over Lincoln's administration.

Those Congressional radicals who welcomed Wood's appointment to the convention had reason to believe he was one of them. Wood had been among the first Whigs, a national party dissolved by U.S. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas's Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, to subscribe to the new Republican Party and its 1856 platform demanding a limit to slavery and denying its extension into free territories.

A native New Yorker, Wood was known for anti-slavery sentiment. He considered his life's greatest achievement his work in 1824 to prevent an attempt by the Illinois General Assembly, dominated by transplanted southerners, to turn the six-year-old Illinois into a slave state. Voters in the Illinois Military Tract, which he worked, opposed a referendum to create a slave constitution by a 90-to-10 ratio. Statewide, the ratio of defeat was 57 to 43.

Nominated by Abraham Lincoln and other Republicans, Wood was elected Illinois' lieutenant governor at the top of the party's first statewide ticket in 1856. He became governor on March 18, 1860, when Republican Gov. William Henry Bissell died in office.

With business interests pre-occupying him--the reason he declined Republican requests in 1860 that he seek a four-year term as governor, Wood got permission from the Illinois General Assembly to remain in Quincy. Ending its spring session, the legislature was leaving Springfield, which gave Wood little reason to relocate to the capital city.

Wood attended to state business from an office in his family's Greek Revival mansion on the northeast corner of 12th and State streets. He altered a room on the south side of the house to accommodate the official governor's office by extending a parlor over the south porch, which he then enclosed. That nearly doubled the space for his office.

When he conducted official business, Wood closed the double doors between the governor's office and his home's family room. Visitors entered through a doorway on the west side of the porch. The governor invited his visitors to sit in a stiff-backed, horsehair-covered chair alongside his desk, on which lie neatly organized paperwork, an inkstand, and his inlaid black humidor from which he drew cigars. Wood smoked cigars made in Quincy from Missouri leaf tobacco and enjoyed an occasional chew of plug or fine cut tobacco. A spittoon for his expectorations was nearby. The furnishings still can be viewed in the Wood mansion, the largest artifact in the collection of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

His use of the Quincy office enabled Wood to offer his party's dark horse presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, the governor's office at the state capital in Springfield for his 1860 campaign. Lincoln took Wood up on the offer. Wood also allowed Bissell's widow to continue residency in the governor's mansion in Springfield.

John Wood understood as easily as others of his party and northern section that great danger lurked in the historical lessons of the 1856 elections. They were there for all to see.

The North was growing. The South was not. That relationship was upending the compromises that forged a union in 1789 by writing provisions in the Constitution that gave the South control of the federal government -- so long as the provisions remained effective. The constitution's "federal ratio," a euphemistic mechanism that had given the South an extra three-fifths vote for every slave, was no longer enough to keep up with the North's surging population -- and an increasing number of representatives in congress.

In the House of Representatives, Northern attacks on slavery -- the South's institution -- came with greater frequency and greater volume. The silence of Northerner John Wood at the Washington Peace Convention was deafening.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a biography of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

"Abstract of Gov. Wood's Message." The Quincy Daily Whig, Jan. 9, 1861.

Basler, Roy P., ed., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, IV, 1860-1861. 9 vols. New

Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953.

Burlingame, Michael. Abraham Lincoln,: A Life, Vol.2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press, 2008.

"Election of 1856," The American Presidency Project at

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1856

"Great Union Meeting," The Quincy Whig Republican. March 30, 1861.

Gunderson, Robert Gray. Old Gentlemen's Convention: The Washington Peace Conference of

1861. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1961.

Howard, Robert P. Mostly Good and Competent Men: Illinois Governors 1818 to 1898.

Springfield, Illinois: Illinois Issues and Illinois State Historical Society, 1988.

National Party Platforms, 1840-1972. 5th Ed. Compiled by Donald Bruce Johnson and Kirk H.

Porter. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975.