John Wood fights slavery in Illinois

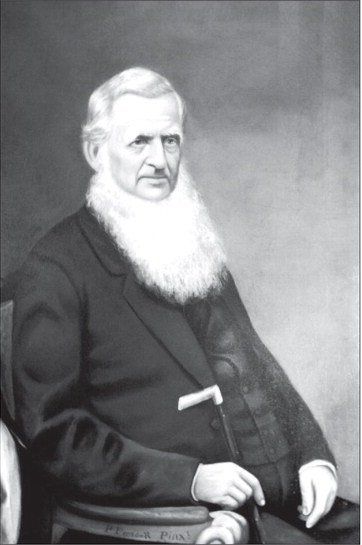

By the end of his life, John Wood could look back on scores of achievements.

At 19, he was among the first Northeastern pioneers in the West. He was a founder of Adams County and the city of Quincy and served several terms as alderman and mayor. He became a state senator, Illinois’ 12th governor and, during the Civil War, the state’s quartermaster general. At the age of 65, Wood led the 137th Illinois Infantry volunteers into a fight against one of the Confederacy’s most brutal generals, Nathan Bedford Forest.

Wood prospered in land speculation, farming, business and banking. His philanthropy started churches — Catholic and protestant — and schools and cemeteries. A humanitarian, Wood helped organize the county’s rescue of thousands of Mormons who Gov. Lilburn Boggs had ordered out of Missouri during the winter of 1838-39. And Wood and his wife, Ann, took into their own home more than a dozen children whose families could not afford to keep them.

Of all his contributions to history and humanitarianism, Wood considered the result of one of his earliest adventures in Illinois his greatest achievement. From the spring of 1823 to the August 1824 election, he joined a fight to stop the state legislature from legalizing slavery in Illinois.

In his search for land and opportunity, the 22-year-old Wood in February 1820 met Edward Coles in Edwardsville. Appointed by President James Monroe, Coles was the federal agent for sales and transfers of land in the 3.5-million-acre Illinois Military Tract between the Illinois and Mississippi rivers. Congress had set aside that land as bounty for veterans of the War of 1812, and Wood had struck upon the idea of speculating in it.

The men of Illinois’ territorial legislature, who had drafted a state constitution in early 1818, were southerners, and they expected to shape their new state with southern institutions, including slavery. They had been comforted by opinions of territorial Gov. Ninian Edwards, a slave owner himself, that they would be able to keep their black property. Indeed, between the time the Illinois Territory was created in 1809 to the time of statehood nine years later, the number of slaves increased from 167 to 917.

New York Congressman James Tallmadge reminded Illinois’ territorial representatives, however, that the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 prohibited expansion of slavery in the territory and he warned it would not become a state if slavery was written into its constitution. As a result, the Illinois Territory’s legislators sent a free-state constitution to Washington, reckoning that once Illinois was in the Union, they could amend the constitution to make it a slave state without congressional interference.

Illinois became the union’s 21st state on Dec. 3, 1818.

Although friends of slavery, the southern- dominated legislature opposed the presence of free blacks in Illinois and began passing anti-black laws at once. By March 1819, lawmakers had enacted a series of “Black Laws” to discourage immigration and emancipation, restrict rights of black and mulatto residents and require free blacks to post $500 bonds and carry papers to prove they were free. Those who could not prove their freedom were subject to immediate arrest and sale into slavery.

Coles was the son of a wealthy plantation owner in Albemarle County, Va., which made his family neighbors with Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe. As president, Madison appointed Coles his personal secretary. President Monroe named Coles minister to Russia in 1816 and federal land agent in Edwardsville in 1819.

With an early conviction against slavery, Coles in 1814 had pleaded with Jefferson, by then retired from public life, to lead a crusade for the gradual end of slavery. Jefferson wished Coles well with the idea and declined to take on the cause.

En route five years later to his new assignment at Edwardsville, Coles freed the slaves (six adults and 11 children) he had inherited and provided 160-acre farms and training to the adults in their new Madison County home.

John Wood had acquired his opposition to slavery growing up in Sempronius, N.Y. Congregationalists there had formed a core in the central New York abolitionist movement from which sprang a sophisticated station on the Underground Railroad into Canada.

Traveling west, Wood spent more than a year in Cincinnati and the Ohio Valley then continued on to Illinois. He was among an increasing number of antislavery men moving into the state who met Coles in the Edwardsville land office. Coles’ growing acquaintances and growing reputation for integrity landed him on the ballot as one of four candidates for governor in 1822.

Coles’ victory that August shocked slavery’s proponents in Illinois. Each of the two pro-slavery candidates, Supreme Court Justices Joseph Phillips and Thomas Browne, favored a slave constitution. But their contest split the pro-slavery vote, 32 to 29 percent. James B. Moore of Monroe County took 6 percent of the vote. Coles was elected with only 33 percent of the vote. Voters in Pike County, which included today’s Hancock and Adams counties, where Wood resided, gave Coles 85 percent of their vote.

In his inaugural address, Coles disturbed the mostly pro-slavery General Assembly by demanding justice for blacks. He sought an end to an indenture system that was slavery in all but name — indentures could last 99 years — and asked for an end to the state’s Black Laws and what he called the kidnapping of free blacks.

Legislators responded by launching a campaign for a referendum to initiate a constitutional convention. They contended that the move was to enact economic reforms that would improve conditions created by the economic Panic of 1819. But since most members of the General Assembly favored slavery, anti-slavery proponents were certain that its veiled purpose was to legalize slavery in Illinois.

Enacting a constitutional convention required a two-thirds vote by each house of the General Assembly. The senate had the votes. When the house fell one vote short of passing the referendum, pro-slavery legislators unseated Pike County Rep. Nicholas Hansen, who had deserted them once, and replaced him with Rep. John Shaw, who voted for the referendum. The maneuver put the referendum on the ballot for the Aug. 2, 1824, election.

In the cause he was about to undertake, Wood would help assure that Pike County would not serve the interests of human bondage again.

Coles donated his four-year salary as governor to the anti-convention cause and recruited friends, including John Wood, throughout the state to join him in his crusade against a slave convention.

By that time Wood had achieved a sizable acquaintance and reputation among the residents between the rivers, and over the next 18 months he promoted the anti-convention cause. On the day before the election, nearly 50 men gathered with Wood at “The Bluffs,” as Quincy was then known.

They saddled up and rode 40 miles south to Atlas in Pike County, the closest polling place, where they would cast their votes the following day.

The convention lost across the state by a ratio of 57 to 43. In the Military Tract, where Wood had fought slavery’s introduction into Illinois, the margin against slavery was 90 to 10.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

Berwanger, Eugene H. The Frontier against Slavery: Western Anti-Negro Prejudice and the Slavery Extension Controversy. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971.

Ford, Thomas. A History of Illinois from its Commencement as a State, 1818-1847. Vol 1. Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1945.

Leichtle, Kurt E. and Bruce G. Garveth. Crusade Against Slavery: Edward Coles, Pioneer of Freedom. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. 2011.

Litwack, Leon F. North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790-1860. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

Pease, Theodore Calvin. Illinois Election Returns, 1818-1848. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Library. 1923.

Preliminary Report on the Eighth Census. 1860. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1862.

Tillson, John. History of Quincy. In William H. Collins and Cicero F. Perry, Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1905.

"Uncovering the Freedom Trail in Auburn and Cayuga County, New York." http://www.co.cayuga.ny.us/history/ugrr/report/PDF/5q.pdf

Washburne, E. B. Sketch of Edward Coles, Second Governor of Illinois, and of the Slavery Struggle of 1823-4. New York: Negro University Press, 1969.