Judge's antislavery decision redeemed his reputation

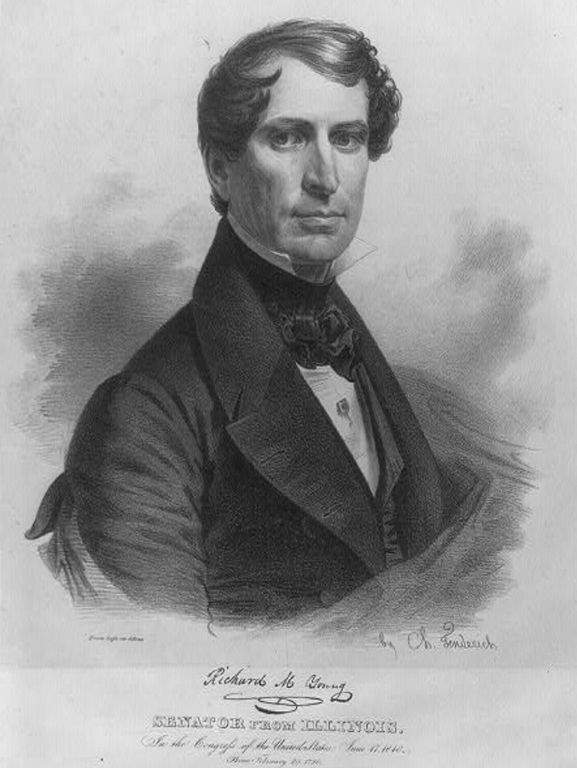

Illinois' Constitution of 1818 started the evolution in the state's court system in which Quincy jurist Richard Montgomery Young figured prominently.

Young's career began in the courts, was nearly irreconcilably damaged when he left them, and won redemption for him when he returned.

The Constitution established a Supreme Court consisting of a chief justice and three associate justices appointed to six-year terms. The justices also served as judges in the circuit courts of four new judicial districts. When the terms of the first justices expired in 1824, the Legislature reorganized the court system. It relieved the justices of circuit court duties, created a fifth judicial circuit, and appointed five circuit judges. One was 26-year-old Richard Montgomery Young, who would preside over the fifth judicial district. Its territory stretched from the confluence of the Mississippi and Illinois rivers to the state's northern border and east to the shore of Lake Michigan.

Young had moved in 1816 from Kentucky to Jonesboro, Ill., and was admitted to the bar in 1817. In 1820, Union County voters elected him to the Illinois House of Representatives. It was both a successful and disastrous term for him. At the age of 22, he successfully championed a bill, controversial throughout Illinois, to charter a state bank. His own party scorned him. His Southern Illinois constituents forced him not to seek a second term.

Appointed a circuit court judge in 1825, Young spent his first two years in Galena, a clamorous lead-mining region in the new fifth judicial district. He opted to move to a quieter Quincy, also part of the fifth circuit, in the spring of 1831. He bought a 200-acre farm 3½ miles east of the city--on the northeast side of today's 48th and Broadway streets--and built a framed prairie cottage, two tenants' cabins and outbuildings. He planted an apple orchard and peach, plum, and cherry trees. And there were born the Youngs' daughters, Bernice Adelaid and Matilda James. In 1835, he sold the property for $2,500 to John Cleaveland, a contractor who had moved to Quincy from Sandy Bay, Mass., a year earlier, and who between 1835 and 1838 helped the city's founder, John Wood, build his Greek Revival mansion near today's 12th and State streets.

In 1835, Young moved his family into a two-story brick house he built on the north side of Hampshire Street between Fifth and Sixth streets. The Quincy Daily Herald would later describe the house as a center of hospitality and social life in Quincy. In 1856, Judge William A. Cather bought the property, tore the house down and built the Cather House hotel. It is the site of today's New Tremont Apartments and the WGEM studios.

Active in business, Young founded, provided editorial direction and wrote for Quincy's first newspaper, the Illinois Bounty Land Register. The newspaper pledged itself editorially to the Democracy Party of Andrew Jackson. Its copy, however, was bland -- filled with land and property sale notices and foreign news. Young drew a stir locally, however, with an advertisement he placed in the Register offering $50 for the return of a runaway slave.

Young had owned other slaves. His purchase of a 5-year-old child named Mary for $75 was recorded in the Jo Daviess County Courthouse on July 24, 1830. The bill of sale promised her emancipation at age 18.

Although his judicial district spanned more geography than any other, Young managed to attend each term of the Supreme Court in Springfield and paid at least one visit each session to the Legislature in Vandalia. He was esteemed as one of the state's most popular men -- and one of the most well-informed. With inside information, Young became the chief adviser to a company formed by a group of Quincy businessmen to build a railroad from Quincy to either Beardstown or Meredosia. Ultimately reaching Springfield, the Northern Cross was the oldest railroad in Illinois, from which the Wabash and CB&Q grew. It was the only railroad project completed in the failed statewide Internal Improvements program of 1836-37.

Young resigned from the circuit court in 1837 when, as the chosen candidate of state Democratic Party chairman Stephen A. Douglas, the General Assembly elected him to the U.S. Senate. Young prevailed over Abraham Lincoln's candidate, Archibald Williams of Quincy, by a vote of 62 to 17. In the Senate, Young did little to distinguish himself, by which he might have been re-elected had he not taken on a responsibility for which he was wholly unfit. Appointed by Gov. Thomas Carlin of Quincy, he was commissioned to sell $4 million in bonds to finance the completion of the Illinois-Michigan Canal. Young joined three colleagues in London where they deposited $1 million in bonds in a seller's hands without security. The misfeasance cost the state $392,400. Condemned by a legislative investigating committee, Young was persuaded not to run again in exchange for a promise that he could return to the state Supreme Court to finish his public career.

What might have been a quiet retirement ended up a fortuitous redemption of the legacy of Young. In 1845, he wrote the decision in Jarrot v. Jarrot, a case in which a slave owner was sued for a slave's back wages. Once a slave owner himself, Young ordered the wages paid, asserting that Article 6 of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 meant exactly what it said. Its author, Thomas Jefferson, had written, "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party has been duly convicted. . . ."

Young's decision effectively ended slavery in Illinois in 1845.

Appointed commissioner of the federal land office by President James Knox Polk, Young and his family moved to Washington, D.C., in 1847. In 1849 he was replaced, elected clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives, and in 1851 returned to the practice of law. His prominence fading, Young suffered a mental illness and was confined to the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington in 1860. He was released within six months but remained secluded at home, where he died Nov. 28, 1861. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington.

Reg Ankrom is a former executive director of the Historical Society and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources:

Ankrom, Reg, Stephen A. Douglas: The Political Apprenticeship, 1833-1843. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Publishers, 2015, Pages 44, 100.

"Asbury, Henry, Reminiscences of Quincy, Illinois, Quincy: D. Wilcox and Sons, 1882, Page 57.

Dittmer, Arlis, "Story of a Familiar Blessing Hospital Picture," The Herald-Whig. Quincy, Ill., Dec. 29, 2013.

Hand, John P. "Negro Slavery in Illinois," Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 15. Springfield: Illinois State Journal Co., State Printers, 1910.

"Illinois Senatorial Election," Illinois Bounty Land Register, April 24, 1835, Page 2.

"Prairie Cottage for Sale," Illinois Bounty Land Register, May 22, 1835.

"Searching for Richard Young," Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 17, 1905.

Selby, Paul and Newton Bateman, Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois. Chicago: Munsell Publishing Co., 1921, Page 603.

Snyder, Dr. J.F., "Forgotten Statesmen of Illinois: Richard M. Young," Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol 11. Springfield: Illinois State Journal Co., State Printers, 1906, Pages 305-307, 312, 315, 317, 320.

Tillson, John Jr., History of Quincy. Chicago: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905, 42.

"Truth about Judge Young," Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 19, 1905, Page 5.

Wilcox, David F., Quincy and Adams County History and Representative Men, Vol. 1. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, Pages 1919, 138, 139.

"Young, Richard Montgomery," Biographical Directory of the United States Congress at http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=Y000050