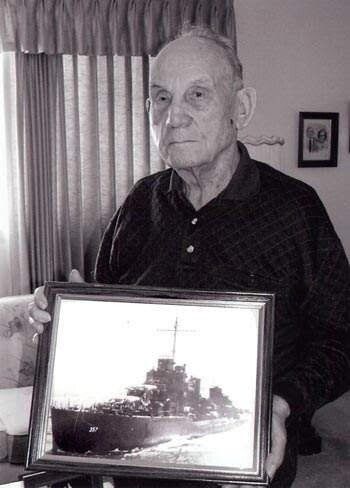

Kenneth Fielding: Pearl Harbor Attack Survivor-

Quincy native Kenneth Fielding stands with a photograph of the USS Selfridge, the ship he served on at Pearl Harbor when Japan attacked the base on December 7, 1941. Fielding spent six years in the Navy and all four years of the U.S. involvement in World War II, during which 56 of his ship’s men died in combat. (Photo courtesy of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County)

“A date which will live in infamy” President Franklin Roosevelt

Quincy native Kenneth Fielding was on the deck of the USS Selfridge, an American naval destroyer ship tethered to five other destroyers at Pearl Harbor Naval Base in the Hawaiian Islands on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941. Fielding had been stationed there for nearly a year as a First Class Storekeeper, who also manned the four-barrel 1.1-inch/75 millimeter antiaircraft guns during combat. Less than 24 hours earlier, the Selfridge had returned to Pearl Harbor following a routine operation. At 0751 hours, just minutes before morning colors, a Japanese plane launched a torpedo against the USS Raleigh, a light cruiser anchored nearby. The attack began the concerted two-hour Japanese torpedo and bombing raid that forever changed world history. Fielding was 19 years and seven months old to the day.

Within minutes of the general quarters alarm sounded by the Selfridge’s deck officer, Fielding assumed his battle station and began firing on incoming Japanese planes. In his report, Captain Wyatt Craig noted that his ship’s guns were first to fire from ships docked in the harbor. One enemy plane Fielding fired upon crashed and another catapulted half-way up a hill inland.

In a 2009 interview with this author for the Veterans’ History Project, Fielding reflected. “Before the Jap attack, the captain had told us there would be no more drills for a while, so most men didn’t sense anything brewing. At first, we thought it was an Air Corps fly-over, and even after the bombing started, we weren’t sure who was attacking us.”

That surprise bombardment devastated the fleet of ships, aircraft, and amphibious equipment, and inflicted more than 3,500 casualties, including 2,403 American servicemen killed. The next day the United States declared war on Japan and entered World War II.

The Navy ordered the Selfridge to patrol the entrance of the harbor and, a couple of weeks later, ordered her to sail toward Wake Island. The ship only got to the Prime Meridian when Wake fell to the Japanese. The aircraft carrier alongside the Selfridge took a massive torpedo hit and the entire scene burst into flames.

After escorting the damaged aircraft carrier to Seattle, Washington, the Selfridge led four ships of U. S. Marines to New Zealand and later picked them up before sailing to Guadalcanal. Fielding chronicled the events that followed. “We were the last ship in our squadron and near the edge of the Coral Sea when 40 Bettys [Japanese bombers] came in on us. We lost the Lexington, the oldest U. S. aircraft carrier in World War II, and five cruisers, and the USS Chicago caught a torpedo that knocked out her bow. One merchant ship turned over.”

“Soon after that battle, the Selfridge patrolled near Vale in the northernmost Solomon Islands. The date was October 6, 1943. Suddenly, we engaged the Japanese in combat. Near the beginning of the fight, the middle ship in our squadron got torpedoed and the ship behind rammed into her deck. Japs directly hit our ship and it exploded into a ball of fire. After we ran out of ammo and torpedoes, we began using flash-less powder, then shooting smokeless powder. Fifty-six of our men died that day with 15 or 16 left badly wounded. One of our men went overboard that night, and the next day a PBY [patrol boat] rescued him amid several hundred Japanese bodies floating in the water.”

Many other battles and naval operations followed for Petty Officer Fielding aboard the USS Selfridge before WWII ended in the Pacific Theater on August 15, 1945. This ceasefire occurred after another Quincy man, Army Air Corps Colonel Paul Tibbetts, dropped atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in Japan from a plane named after his mother, Enola Gay.

The military decorated Fielding for his service in World War II, but when asked about courage and heroism in combat, he said: “They are overdone. We had a job to do, and we did it. We carried out our duty the way we were taught to respond. We’ve been called the ‘Greatest Generation,’ but my father raised three boys by himself in the 1930’s and never knew what he was going to put on the table for the next meal. World War II kept tyranny off of our shores and made the world a safer and better place, allowed us to prosper. The war taught us that freedom has a price and veterans pay for it.”

Kenneth “Speedy” Fielding was born on May 7, 1922, in Quincy, the son of Clarence and Ethel Fielding. After attending public schools in the city, he entered the Navy and completed basic training at Great Lakes Naval Station in North Chicago. He served six years in the Navy before being honorably discharged and returning to the United States. His military service taught him valuable lessons about life and the discipline and hard work it involved continued to direct his civilian career.

After leaving the Navy, he worked for three years in California at a military shipyard before moving back to Quincy. On April 20, 1948, he married Mary Celeste Taylor and began a 33-year tenure with the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, working his way from painter to lock master at Saverton, Missouri’s Lock and Dam #22. The Corps also stationed him at Lock and Dams 14, 17, 18, and 20.

Kenneth Fielding died at age 92 on February 20, 2015, a resident of the Illinois Veterans Home in Quincy, where—among some of the remaining World War II veterans—he lived his last days. The U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that only about one percent of the 16.1 million World War II servicemen are alive today. A model of the USS Selfridge rested on the mantle place in Fielding’s home in Quincy, a poignant reminder of his service to our country. Alongside it was draped the American flag that flew from his ship’s yardarm on that fateful December day 80 years ago.

Joseph Newkirk is a

local writer and photographer whose work has been widely published as a

contributor to literary magazines, as a correspondent for Catholic Times, and

for the past 23 years as a writer for the Library of Congress’ Veterans History

Project. He is a member of the reorganized Quincy Bicycle Club and has logged

more than 10,000 miles on bicycles in his life.

Sources

“A-Bomb Crew Thoughts on First Drop.” Quincy Herald-Whig, Aug. 8, 1954, 31.

“Congress Declares War: Honolulu Loss is 3,000.” Quincy Herald-Whig, Dec. 8, 1941, 1.

Craig, Wyatt. “USS Selfridge, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack.” January 15, 1942.

http://www.history.navy.mil/docs/wwii/pearl/ph81.htm

.

Fielding, Kenneth. Interview by Joseph Newkirk for the Veterans’ History Project, Nov. 2009.

Prange, Gordon W. Pearl Harbor: The Verdict of History. New York: McGraw-Hill, Co., 1986.

Toland, John. Infamy: Pearl Harbor and its Aftermath. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1982.