Letters reveal settlers' attraction to Adams County

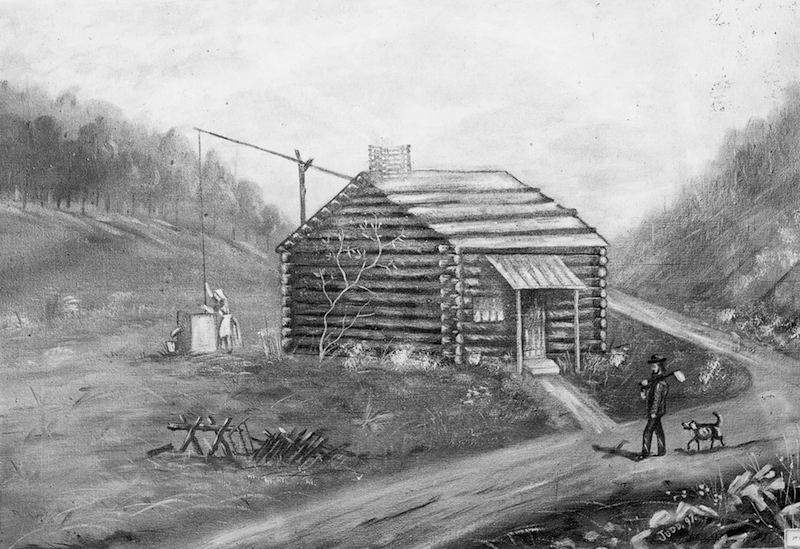

What lured whole families, sometimes whole extended families, to leave comfortable lives behind in New England, New York and Ohio, and come west to Adams County?

Certainly the prospect of free or reasonably priced land made the move attractive and is often cited as the primary lure. But the letters written by the some of the pioneers and sent to their families and friends back East were full of reports of other things besides procuring the land cheaply. They described high crop yields and good prices for them, thriving livestock and bounties of wild food sources.

Concerns about the Indians who were being displaced seemed secondary. Difficult travel conditions were mentioned only matter-of-factly, as though a normal part of life.

More than 20 letters and personal business papers written for or between members of the Stewart family between 1798 and 1849, were found in the attic of an old farmhouse east of Quincy about 1970 by then-owners, the McGartlands, and were recently donated to the Historical Society.

The papers reveal that three generations of the Stewart family had settled in Rome and Athens in Gallia County, Ohio, around 1800. Gallia County is in the extreme southern part of Ohio, bounded by the Ohio River. In the spring of 1832, Martin Stewart left home to become the first homesteader on a prairie farm in Adams County.

Just two months later, on June 3, Stewart was settled in as a farmer. He wrote to his parents and friends with a full description of the trip from Ohio to Quincy. "We left the mouth of the [H]ocking [River] April the 17th about two o'clock p.m. and Monday the 23 we were at Cincinnati in the afternoon. The town has greatly improved since I was there six years ago. It is really a sight to see the different machinery that is going on there. Samuel and I went into the Latinsisium and there we saw many curious things. The fire ‘king' was there and I saw him eat burning coals and melted lead. This day the 24th we left the town."

Stewart's next stop was Louisville, Ky., which he described as "a fine large town." The Ohio River was the main waterway for bringing settlers west, but the waterfalls impeded boat traffic, so a canal had been built around them. Apparently some chose to "run the falls." Stewart wrote, "[The] canal there is a splendid piece of work and money. The thirtieth we run the falls and paid the freighter three dollars."

To that point, Stewart had not specified whether he was traveling by flatboat or steamboat, but about his next vessel he left no doubt: "Tuesday May the 7, I ship[ped] aboard the steamboat Cleopatra. Thursday night there arose a violent storm and we landed and lay all night Sunday. We then landed at St. Louis, a fine large town on the Mississippi. Hear we lay two days and the wind blew many bugs. Tuesday we left St. Louis and Thursday we landed at Quincy."

Stewart arrived in Quincy on May 10, and the entire trip from Gallia County, Ohio, cost him slightly less than $14. Because of the ease and low cost of water transportation, thousands of Adams County's earliest settlers arrived on steamboats.

Stewart rented a farm in the Mississippi bottom about two miles inland and 10 miles from Quincy (he did not specify in which direction), and immediately turned to the river to fish for food. The first fish he caught weighed 6 pounds, and the second weighed 45 pounds. He claimed such a catch was not unusual.

Stewart went on to describe the soil as "rich and fertile." Corn was selling for 50 cents per bushel and wheat at 75 cents per bushel in Adams County. He said that cows were selling from $10 to $14 apiece, but the ones here already were larger in May than the ones in Ohio normally were in the fall, and gave much more milk. He had acquired about 60 horses and about twice that many cattle. He said pigs were plentiful.

Like many of the early Adams County settlers, Stewart wanted his extended family to follow him here. As if the description of the safe and economical travel, lush land, easy fishing and large livestock weren't enough to lure them, he added his ideas for their economic gains, too. "Tell Garrett and Bradley to dry all the fruit they can if they intend to come to this country, for fruit bring[s] a good price here. It rates at two dollars, even at three and four dollars. Applesauce would sell well here."

Stewart did add one negative note: "Indian wars" were in progress, and in one clash, 36 Indians, 11 men and three women of the settlers had been killed. But that information was added almost as an afterthought.

Martin and his wife reared a large family in Honey Creek Township, where his brother Bradley also married and settled. His brother Garrett became a prominent man in Burton Township. He and his wife's graves are in the Independence Cemetery, also known as the Stewart Cemetery. The graves of Martin, Garrett, and Bradley Stewart's parents are in a rural cemetery between Big Neck and Golden.

The McGartland/Stewart letters demonstrate that the county's first settlers' enthusiasm did, indeed, attract many others to settle Adams County.

Author's note: Spelling, punctuation, and paragraphs in the letter were modernized for transcription. Wording was not changed.

Linda Riggs Mayfield is a researcher, writer and online consultant for doctoral scholars and authors. She retired from the associate faculty of Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing and is on the board of the Historical Society.

Sources

Find a Grave. www.findagrave.com

History of Adams County, Illinois.Murray, Williamson, & Phipps. Chicago, 1879.

Original correspondence and 1985 Transcription: The McGartland Papers Collection. Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Stewart Clan Magazine. Geo. T. Edson, publisher. Vol. 1, No. 1, July, 1922.