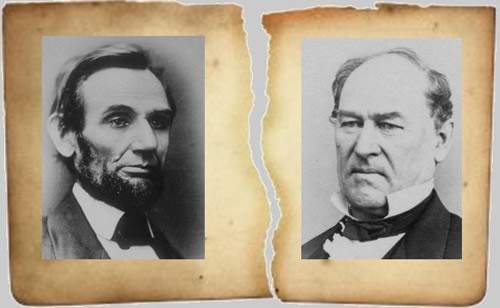

Lincoln parts with Browning over Emancipation

Abraham Lincoln's forgiveness was legendary. But when one of his closest friends, Republican U.S. Sen. Orville H. Browning of Quincy, opposed the president's Emancipation Proclamation -- Lincoln's plan to liberate slaves in rebelling states on Jan. 1, 1863 -- the president cooled toward him.

Browning and Lincoln had been friends from their days as Illinois legislators a quarter century earlier. The friendship had given Browning, appointed U.S. senator after Stephen A. Douglas's death June 3, 1861, easy access to the White House during the first two years of the Lincoln presidency. But Browning by mid-1862 found Lincoln withdrawing from him. Over the next two years, there would be far fewer invitations to the White House and few requests for advice. Although Lincoln in February 1862 had favored Browning for an opening on the U.S. Supreme Court, Browning in August saw the dream vanish with Lincoln's appointment of Judge David Davis of Bloomington. Even inside information as late as December 1862 from Post Master General Francis Blair and Marty Todd Lincoln that the president was going to appoint Browning secretary of interior did not materialize. Said Lincoln historian David Donald, Browning seemed not to realize that his record of opposing the Emancipation Proclamation "made him exactly the kind of man the President said would ‘cause him trouble, and be in his way.'"

Evidence of the split in his relationship with Lincoln became clear to Browning on Sept. 22, 1862, when he learned at the same time everyone else in the country did that the president was giving states in rebellion 100 days to return to the Union or lose their slaves to freedom. Uncharacteristically, Lincoln did not consult or inform Browning about it.

In the weeks before he learned of Lincoln's plan for emancipation, Browning had strongly opposed another radical proposal, a second Confiscation Act. The measure provided that fugitive slaves who made it to Union lines would be freed and not returned to their slave owners, as the fugitive slave law required.

On the morning of July 14, 1862, the day after the bill was passed, Browning rushed to the White House and "expressed to him (Lincoln) very freely my opinion that it was a violation of the Constitution and ought to be vetoed."

A veto "would be worth 100,000 muskets" in the border states (Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland and Missouri), Browning told Lincoln, but "approval would cost the Union its friends there."

Browning was unaware that Lincoln already had made up his mind to emancipate slaves in rebel states. Lincoln believed the Confiscation Act and a contemporaneous Militia Act, permitting blacks to enlist in the Union army, would be useful in preparing public opinion for his Emancipation Proclamation. On the day the confiscation bill passed, July 17, 1872, Lincoln revealed in a private conversation with Cabinet Secretaries William Seward and Gideon Welles his plan to issue an Emancipation Proclamation under the war powers he believed the constitution gave him as president. He did not tell Browning.

Lincoln found Browning's conservative arguments over the past 12 months contradictory. Browning had taken the president's position when radical Republicans argued that the constitution fixed war powers with the Congress. Browning cited an 1849 Supreme Court decision that the powers of Congress were not expanded by war.

"The functions of Congress are civil and legislative only," Browning said. "It can exercise no war powers."

These were powers the Constitution provided only to the president, said Browning.

Yet Browning had defended Gen. John C. Fremont's proclamation of Aug. 30, 1861, to liberate slaves in Missouri. Fremont was the commanding general of the Union Army's Department of the West, headquartered in St. Louis.

Browning biographer Maurice Baxter wrote that Browning thought loyal citizens of Missouri supported Fremont's campaign, including this emancipation proclamation, to clear Missouri of secessionists. When Browning learned that Lincoln had forced Fremont to revoke his proclamation, Browning wrote a 13-page letter to the president protesting that "there has been too much tenderness toward traitors and rebels."

No criticism of the president's order to Fremont cut Lincoln more deeply than Browning's, according to Lincoln scholar Allen C. Guelzo. Lincoln responded to Browning in an upbraiding tone, marking his letter "private and confidential."

"Yours of the 17th is just received," Lincoln wrote, "and coming from you, I confess it astonishes me. That you should object to my adhering to a law, which you assisted in making, [Browning had voted for the first Confiscation Act] and presenting to me, less than a month before is odd enough. ... Genl. Fremont's proclamation, as to confiscation of property, and the liberation of slaves, is purely political, and not within the range of military law, or necessity ... That must be settled according to laws made by law-makers, not by military proclamations. The proclamation in the point of question is simply ‘dictatorship.' It assumes the general may do anything he pleases."

Lincoln scolded Browning for his inconsistency: "... If you will give up your restlessness for new positions, and back me manfully on the grounds upon which you and other kind friends gave me the election, and have approved in my public documents, we shall go through triumphantly."

Browning answered in another lengthy letter to Lincoln, respectful of the president but arguing that Fremont's actions were "fully warranted by the laws of war." Browning said established international law provided for unlimited confiscation of an enemy's property. Secessionists were enemies beyond the law, summed up Browning's legal justification of Fremont.

Finding Lincoln resolute about his Emancipation Proclamation, Browning became despondent, according to biographer Baxter. In his diary in the months after September 1862 Browning records conversations only with men who agreed with his view that Lincoln's proclamation was unfortunate and unconstitutional.

"It could do no possible good," Browning lamented in his entry of Oct. 14, "and certainly would do harm in uniting the rebels more firmly than ever, and making them fight with the energy of despair." He believed it also would divide the north.

Browning's despondency also showed up after his return to Quincy in late October 1862 in time for the November election. Opposed for re-election by Democrat William A. Richardson of Quincy, Browning had been invited to speak to a public meeting at Concert Hall in Quincy on October 29. But he left, refusing to speak because of "extravagances ... which I could not approve" and "sneers at the constitution." The "extravagances" and "sneers" came in speeches for emancipation as a war measure from Col. Moses M. Bane of Payson and Gen. Benjamin Prentiss of Quincy, both respected veterans of the April 6, 1862, Battle of Shiloh.

In its Nov. 3, 1862, issue, the Quincy Whig complained that Browning was not supporting his own Republican ticket. And the next week the Whig reported that Browning "astonished his hearers by the sage advice that they should be sure to vote the best ticket, leaving it to be inferred that he did not know which was the best ticket."

With Democrats controlling the legislature, which elected the state's U.S. senator at the time, Browning lost his senate seat to Richardson.

Back in Washington, Browning continued to denounce the proclamation, seeking its withdrawal but finding the president steadfast. Browning called on the president at noon Nov. 29. Finding Lincoln amiable he took the occasion to blame Lincoln for the Republican losses. Browning "told him that his proclamations had been disastrous to us."

Browning noted in his diary that Lincoln heard him out but "made no reply."

Lincoln's ear was no longer friendly to Browning's voice. Browning's further efforts to stop the Emancipation Proclamation proved futile.

"There is no hope," wrote Browning in his last diary entry in 1862. "The proclamation will come -- God grant it may not be productive of the mischief I fear."

While he was no longer a U.S. senator, Browning remained in Washington as lawyer and lobbyist. His interactions with Lincoln diminished significantly. The number of Browning's meetings with Lincoln declined from 164 during 1861 through 1862 to 47 meetings in the last two years. Invitations by Lincoln to Browning dropped from 38 to six.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

LANDMARK DOCUMENT

This New Year brought the 150th anniversary of a landmark American document of freedom. On Jan. 1, 1863, President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation became effective, an action that would render irreversible the promises of the Declaration of Independence.

The response of Quincy newspapers was divided.

"President Lincoln should preserve the pen with which the edict of emancipation was written," the Daily Whig editorialized on Jan. 9, 1863. "It should be deposited with the award of Washington and the cane of Franklin at the Federal city, as a perpetual memorial to one of the grandest works ever accomplished."

"It is in violation of the Constitution which Mr. Lincoln is sworn to ‘observe, protect and defend,' for no power is granted in that instrument, either as a war measure of a peace measure, to interfere with any local institutions of a State," said the Quincy Herald on Jan. 5.

Sources

Baxter, Maurice. Orville H. Browning, Lincoln's Friend and Critic. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1957.

Donald, David. We Are Lincoln Men: Abraham Lincoln and His Friends. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003.

Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004.

The Lincoln Institute. "Mr. Lincoln's White House." The Lehrman Institute, 2009-2013. http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/inside.asp?ID=153&subjectID=2

Pease, Calvin, ed. The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, Volume 1, 1850-1864. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Library, 1925.

Pinsker, Mathew. Lincoln's Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldiers' Home. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Quincy Whig. November 3 and 10, 1862.

Rawley, James A. Abraham Lincoln and a Nation Worth Fighting For. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.