Lincoln Praised by Former Slaves who Became Quincyans

On January 1, 1863, an important meeting was held at the African Methodist Episcopal (A. M. E.) Church among Quincyans of African ancestry, including many citizens who had personally known slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation took effect that day, and although the Civil War was raging, anti-slavery Americans saw new hope for the nation with this bold strategy.

According to the January 10, 1863 Daily Whig, the Reverend Newsom called everyone to order, and Edward Fulton was elected president of the meeting. He stated that the purpose of their meeting was of great importance to people of color in Quincy and throughout the U.S. They met to “celebrate the birthday of a nation, the downfall of slavery, and to give honor and thanks to the great friend of the down-trodden and oppressed.”

Then the meeting president E. A. Fulton addressed the earnest crowd. They gave gratitude to God and agreed that Providence caused President Lincoln to issue his Proclamation on September 22, freeing slaves in rebellious states and parts of states found in rebellion. The group resolved that Lincoln was the “proper man for the times, as President of the United States and therefore our thanks are tendered to him for his firmness of character as chief executor of the nation, to do right, and deal out justice to the oppressed as well as to traitors.” They decided they wanted to defend liberty to the last moment and adopted the language of Patrick Henry: “Give me liberty or give me death.”

The meeting participants acknowledged that their God-given rights were unjustly taken away, while approving the restoration of those rights “purchased by our forefather’s sufferings, blood, and death in the Revolution.” They would defend a government that would defend their rights and protect them as citizens, and rally if it were “endangered by rebellious traitors at home or enemies abroad.”

Monroe Clark recorded the meeting as secretary and his brother Simeon Clark was one of four vice presidents. The Clark family was once slaves in Kentucky, became free, and later lived in New Philadelphia, Illinois, a town founded by freed slave Free Frank McWorter, before moving to Quincy. A sister, Louisa, married McWorter’s son Squire, and the families knew each other intimately. The Clarks and other former slaves played a vital role in West-Central Illinois’ secret route to Canada for fugitives seeking freedom.

Seven years after the Emancipation Proclamation, the nation had changed dramatically. The Confederacy was defeated, and the 13th and 14th amendments had passed. However, President Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, and Reconstruction was a bleak period to many in our war-torn nation.

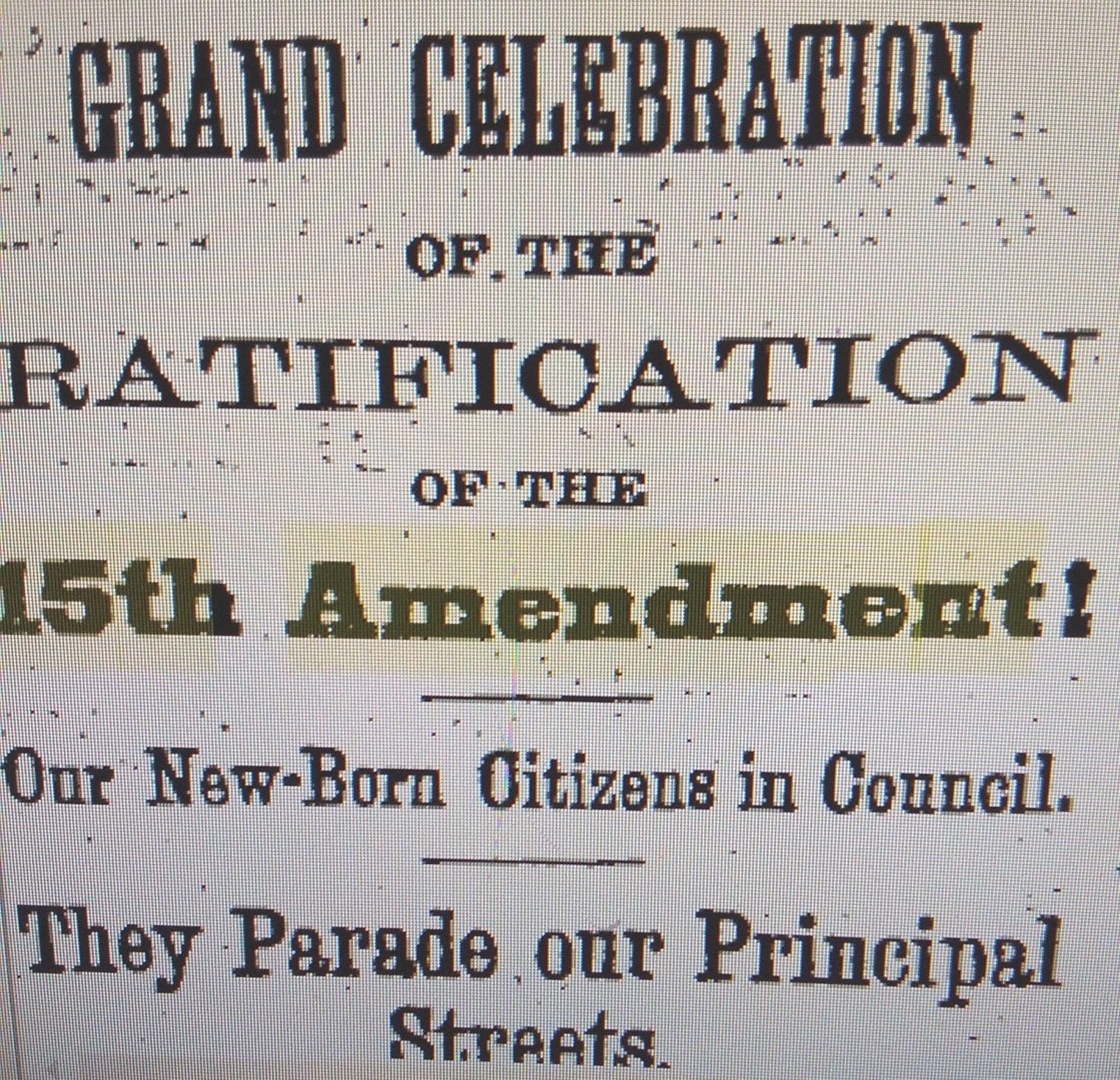

The ratification of the 15th Amendment which prohibited the states and the federal government from denying the right to vote because of color or race in 1870 was greeted with fanfare in Quincy and brought even more hope to former slaves and their descendants. The celebration began at the A.M.E. church with speeches from local citizens. The April 8th Daily Whig relayed events of the day. Cannon fire at 4 a.m. introduced the celebration, and “every boom seemed to say ‘Freedom’ while the everlasting limestone bluffs echoed the response ‘Freedom’.” A procession was formed at the church that meandered through Quincy streets and ended at Pinkham Hall at 4th and Maine.

Portraits of President Lincoln and President Ulysses Grant were displayed from windows of public and private homes on the route. Banners with mottoes acknowledging new freedom were part of the procession, such as: “We Were Always Loyal During the War,” “Our Votes Cannot Be Bought For Whiskey or Money,” “We Have, At Last What We Fought For, Right Of Franchise,” “We Remember the Repeal of the Black Laws of Illinois.”

Rev. Richard Duling of the Jersey Street Baptist Church spoke, and his words are etched in our history: “When the framers of the Declaration of Independence first set up this government, they found slavery already in existence, and they were forced to retain this monstrosity, conceived as it was in sin and brought forth in iniquity. Not because it was popular did they retain it, but because it was localized and could not be banished at the same time that a union of the colonies was to be affected. Such a union was of paramount importance, and the framers of that instrument hoped that after the colonies were united slavery would soon die out.”

He continued, “But it did not die; it grew and waxed strong with the nation’s strength, and spread its shackles in all directions, until it spared not to risk the nation’s life. Not content with the bondage of the Negro, it made slaves of white men, and the world saw preachers of the holy Gospel espousing slavery’s cause instead of preaching peace and good will toward all men. After corrupting the church, it entered the legislative hall – this monster made and unmade Presidents, made and unmade parties; in short, slavery diffused itself throughout every branch of government, and none had the manliness to resist it or show its deceitful wickedness.”

Rev. Duling said John Brown and his followers aroused the public heart and Bleeding Kansas awoke many Americans to the shame and wickedness of slavery, and that it was not until the war that many people knew the real wickedness of slavery. He said they were here to commemorate the death and final burial of slavery, and proclaimed President Lincoln as one who ‘unlocked their dungeon”; and opened the benefits of citizenship at the ballot box. He said they would cherish and teach their children to honor Lincoln’s sacred memory.

The day commenced with lively discussions of the war and the passage of the 15th amendment. Abolitionists of all backgrounds contributed to this celebration of freedom.

Sources

“A.M.E. Church is One of Pioneer Groups in City.” Quincy Herald-Whig, June 21, 1942.

“Colored Voters. Meeting at the Colored Baptist Church.” Quincy Whig, Nov. 1, 1882.

“Council Proceedings.” Quincy Daily Whig , Nov. 13, 1854.

“Grand Celebration of the Ratification of the 15th Amendment. Our Newborn Citizens in Council.” Quincy Daily Whig , April 8, 1870.

“Jersey Street Baptist First Negro Church.” Quincy Herald Whig, June 21, 1942.

“Meeting of Colored Citizens.” Quincy Daily Whig, Jan. 10, 1863.

Quincy City Directories: 1865-1876.

Shackel, Paul A. “New Philadelphia: An Archeology of Race in the Heartland.” University of California Press, 2010.

Walker, Juliet E.K. “Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier.” University Press of Kentucky, 1982.