Local boat clubs were regional rowing powerhouses

Go down to Quincy’s waterfront and you will see the historic North Side Boat Club. Walk up close to the sign in front and it may be a surprise to see that the club’s logo is a pair of oars.

And further down Front Street at the South Side Boat Club resides a collection of photographs and trophies documenting the glory this part of Quincy’s waterfront produced, fame that was not powered by motors but by strong backs and oars.

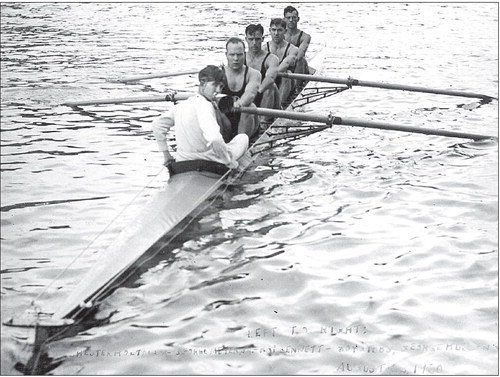

From the 1890s to the 1940s, Quincy was a regional rowing powerhouse. Workers in Quincy’s manufacturing and construction industries gathered after the workday ended to take their racing shells containing anywhere from one to eight rowers — referred to as singles, double/pairs, fours and eights — onto the Mississippi River and Quincy Bay to practice and compete.

The protected bay waters and riverfront provided a good straight stretch of water and enough shoreline (along what was then called Edgewater Park) for 5,000 Quincyans to turn out in July 1910 to watch and cheer on their favorites. Even the Quincy Naval Reserve entered their cutter and whale boat into the races.

Historian Carl Landrum noted in The Quincy Herald- Whig that the South Side Boat Club was founded in 1886 and the North Side Boat Club in 1894. The original South Side Boat Club was organized in a cooper (barrel) shop in a Quincy alley and had only a handful of members. The sport gained popularity, and in 1903, the Quincy City Council recognized its importance by granting use of city land for shell storage.

Longtime South Side members Allie Lymenstull, 88, and Herb Gustafson, 89, recall they were the youngsters when older club members brewed beer for club dances and used nickel and dime slots to raise travel money to attend regattas.

The numerous trophies on display at the South Side Boat Club attest to the fact that the distance from other rowing venues was no problem; club boats (more than 60 feet long for a racing “eight”) were loaded onto train cars on the tracks next to Front Street and hauled to races in St. Louis, Peoria, Detroit, and Chicago on a regular basis.

Quincy rowers even won the national championship in an “eight” in Philadelphia in 1904 and took the national championship the following year in a “four” in Springfield, Mass. In 1930 a crew of Quincyans traveled to Liege, Belgium, for the International Rowing Regatta, barely missing (by 2/5 second) winning the international “four” championship and receiving second place in the world. They had competed and distinguished themselves against an international field and returned home to heroes’ welcomes.

Rowing was one of the first sports in which both men and women competed. The South Side Boat Club created a “Ladies Aid” division in 1910 and fielded a women’s crew in July 1935. In that same month the club’s junior team won the Central States Junior Rowing Tournament, with host St. Louis taking second.

Quincy’s rowing culture ended after World War II, when soldiers returning home were preoccupied with the needs of new families and the dream of home ownership.

Rowers went home after work, not out on the river. Bowling alleys and baseball diamonds with artificial lighting provided an after supper team activity, and the river became a place for motor-powered boats.

While the new sports were no match for the physical and endurance challenges of rowing (which required sustained bursts of full on power beyond the comfortable bounds of aerobic capacity), they allowed for greater participation by regular folks.

Labor-saving conveniences saved time and effort, but the result was that Americans by and large lost touch with intense sustained exertion in work and sport. America’s postwar mindset emphasized “modern” living, a lifestyle that, to the extent possible, supplanted the old physical ways with use of electric and internal combustion devices.

While folks still used their bodies for strenuous physical labor when there was no labor-saving alternative, rowing for sport went away like the all night dance contests and the washboard. Fashion conscious young men wore gloves and hats so as not to look so tanned and “coarse”, and magazines urged homemakers to improve their status by increasing the labor-saving appliances in the kitchen.

New homes and subdivisions were built without incurring the extra cost of sidewalks because modern families used the car to travel, bicycles became children’s toys, and when someone went for a boat ride it usually involved a motor, not oars or a paddle.

The intense exertion required for rowing intervals (“full power 20s” involved repetitions of 20 stroke “pieces” as hard as the crew could pull) required strong commitment, and it was just a whole lot easier to be on a bowling or baseball team where exertion was still intense, but in much shorter bursts.

America’s belief in the value of strenuous activities that produced physical endurance for the regular person drifted off into the smoky haze of the bowling alley and the walking or golf cart driven pace of the golf course.

The new intensive physical sports that did develop like basketball and football involved cutting and moving on the court and field, sometimes damaging joints. The physical toll imposed was so great that many athletes carried a bad knee, ankle or shoulder into their mid-20s, an age when elite level rowers were just hitting their prime.

No longer in use, Quincy’s rowing boats were sent to other communities with surviving rowing programs, and the Quincy waterfront was transformed to a place where motorboats carried people onto the water.

Gradually, the community forgot that Quincy Bay was once the stage for Quincy’s triumph with oars.

Ray Thomas is a former Quincyan (QHS 1970, QU 1974) whose mother, Maggie Thomas, was a longtime Quincy radio and television reporter and an actress. He is a lawyer who lives in Portland, Ore.