Man hung in 1865 for bushwhacking, various other crimes

In 1865 citizens of Quincy took justice into their own hands and hung Thomas Rose from the Hanging Tree on 16th Street between Vine and Prairie for bushwhacking and various other crimes. That hanging tree could be seen until about 1907 when it was finally cut down.

Rose had been operating in the area for several weeks and planned to cap off his raiding with a robbery near Lima and sacking the town of Canton, Mo. Rose was short manpower to achieve his goals, so he contacted a policeman in Quincy who had several times helped Rose to secretly cross the river in a skiff. The man listed in the Chicago Tribune newspaper article as Ben Swarthout, bears the name of a family who served the Union during the Civil War, making this either an instance of the war dividing families, or of confusion on the part of the young man who told the story.

This policeman did find two Quincy recruits to help Rose in his schemes. On the way to join Rose, these men opted to stop at a local tavern for some liquid courage and imbibed heavily becoming drunk. Late in the evening, the policeman, fearing exposure or alternately seeing the possibility of reward money, betrayed the two to the sheriff. The sheriff formed a posse and rode for the Riley farm near Lima Lake where the gang was harbored.

In the attempt to arrest Rose and his gang, several men were wounded and a member of the posse by the name of Trimble was killed. Rose himself was severely wounded by three or four gunshots.

This story is sadly told from the confession of the youngest member of the Bushwhacker's group, a 16-year-old boy sentenced to hang for his part in the raid and for the four shots he fired when the posse arrived. Thomas Wilson was born in Illinois in 1848. His father left to go to the gold fields in California but died on the way. His mother remarried, and Wilson was raised by a stepfather in Carroll County, Mo., after his mother died.

His stepfather was a southern man, and when the war broke out and General Price invaded Missouri, he told his stepson that the two choices were to enlist in the Confederate Army or be conscripted by the Federal Forces, which were soon to follow. Wilson enlisted, then after ten days changed his mind and deserted. Wilson, afraid he would be caught, next reported to the Provost Marshal in Pilot Knob, Mo., but the commander was away, and he was told to come back later. This situation was repeated three times, until young Wilson was persuaded by some companions to go to Illinois. There he found work on a farm south of Rushville, where the farmer, William Edmonton, knew that he was a confederate deserter and held it over him.

Wilson says that, "From the time I came into the State, Edmonton who knew I was a deserter from the rebel army and had also violated the order of the Federal military authorities to report, endeavored by persuasion and by threats to induce me to go back to Missouri and go to bushwhacking. He said I must go willingly or unwillingly or be shot as a deserter."

Wilson reluctantly agreed and left in March with a man named Williamson. They walked about eight miles to a farm near Rushville where a Kentuckian put them up and hid them the next day. Then they stole two horses from a neighbor and moved to a barn near Tennessee, IL, where another sympathizer hid them. This was the pattern for two more nights, before Williamson became worried that the stolen horses would give them away and determined to shoot the horses. Wilson begged to simply turn them loose, but Williamson said the owner was a damned Yankee who "hurrahed" for Sherman and shot them.

The men spent weeks meeting up with other southern sympathizers, hiding by day and moving by night. Some men wanted to rob for money; others were working for the southern cause. Thomas Rose was trying to gather a group of men and they agreed to join him, which led to the robbery of a general store near Lima and plans to rob the bank in Canton, Mo.

After the shootout and capture of the gang at the Riley Farm, it was reported that one member of the bushwhackers was hanged by men from the Lima area, and five others were transported to the jail at Quincy. Some outlaws escaped. By the time the five prisoners reached Quincy, it was apparent that Rose was mortally wounded and might not live until morning.

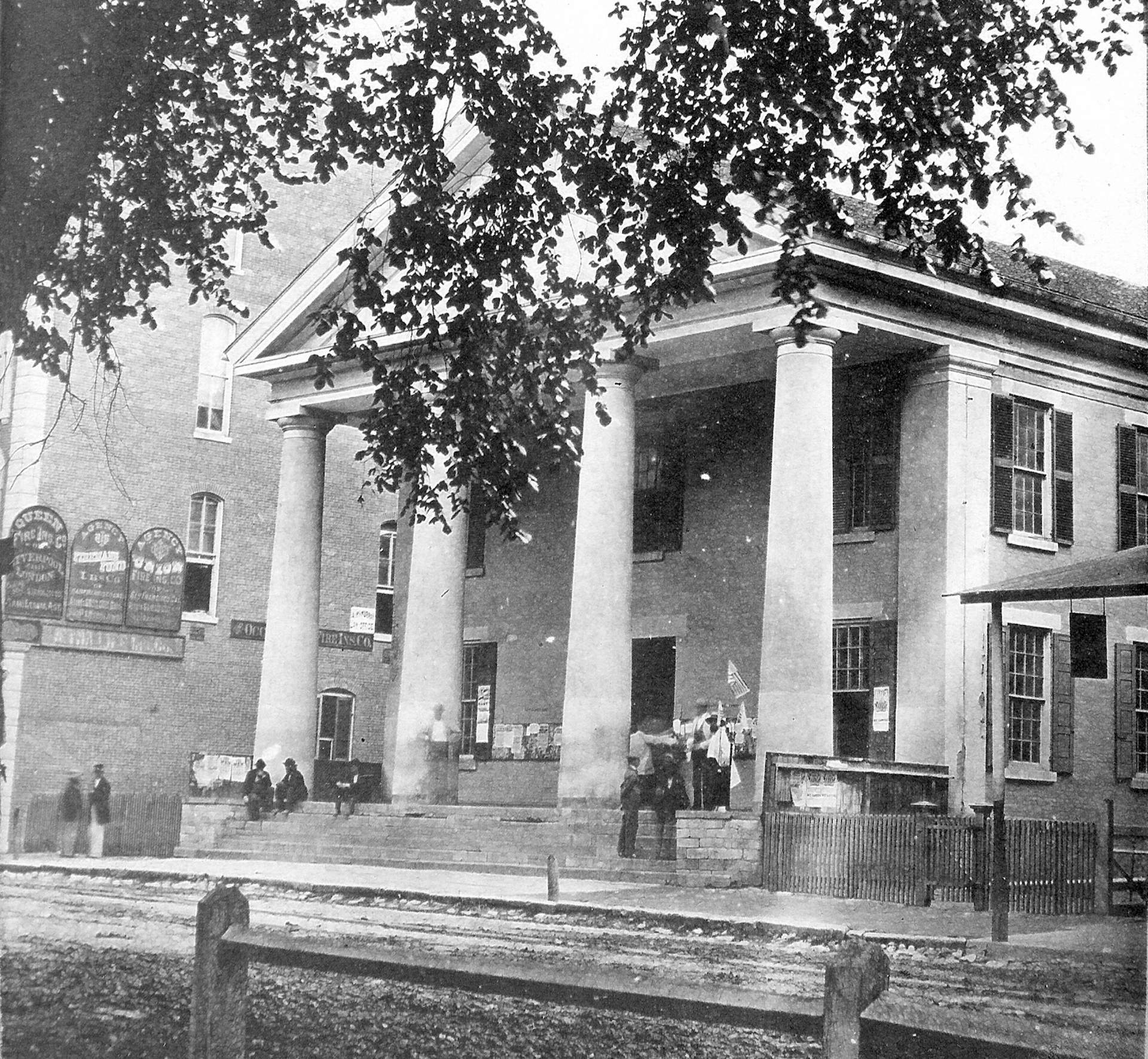

About 11 o'clock that same evening, a crowd had gathered at the jail, at that time in the Courthouse, and soldiers from the local army hospitals broke down the door with a sledgehammer. They took Rose to the hanging tree. Before they lynched the man, they allowed him to speak with a reporter. Rose was too wounded to stand upright and gave his interview lying on the ground after requesting someone to pray with him.

He said he lived near Troy in Lincoln County, Mo, and had a wife and three children. He told a tale of hardship. The reporter had little time and spoke with Rose within a ring of about three hundred people under the branches of the huge old tree. Rose himself could barely talk and was bleeding. The reporter from the Quincy Daily Herald writes, "The crowd were so eager to hang him, that we could gain no more, and being invited to leave the ring, we complied with as much rapidity as possible."

The Quincy Daily Whig and Republican sums up the mood of the city. "Although we cannot approve of the violent and uncertain method of procedures, there is no doubt that Rose richly deserved his fate."

Public sentiment discouraged the hunt for those who perpetrated the lynching, and no one was ever arrested.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson, Ill., and the former executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

"Arrest and Lynching of Bushwackers in Adams County," Quincy Daily Whig and Republican, June 2, 1865

"City of Quincy," Quincy Daily Whig, February 27, 1863, 2.

"Civil War in Lima," Quincy Daily Whig, August 20, 1863, 2.

"Local Affairs, Excitement Wednesday Night," Quincy Daily Herald, June 3, 1865.

"Local Matters," Quincy Daily Whig, June 15, 1861, 3.

"Local Matters," Quincy Daily Whig, October 4, 1862, 3.

"Rebel Bushwacking in Illinois," Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1865.

"The Hanging of Rose," Quincy Daily Herald, June 1, 1865.

The Lynching of Thomas Rose of Lincoln County, Missouri in Quincy, Illinois. Compiler, Thomas Rose. Columbia, MO: Private Printing, 2016.

"True Copperhead Spirit," Quincy Whig, February 7, 1863.

"When Quincy Sent Soldiers to Fight Against Mexicans," Quincy Daily Whig, December 5, 1909.

"When Quincy was the Scene of Lynching," Quincy Daily Herald, February 24, 1917.