Mayor Jarrett was one of those town 'characters'

It is good to remember that the story of a city is made by the entangled threads of the lives of its citizens.

Stories wind together in unexpected ways, and every family has a "character" or two if you care to look. Often they appear in the most unexpected places.

James Jarrett, born in Scotland in 1839, came to America, stopped in St. Louis and arrived in Quincy in 1857.

By 1869 he had established a business providing ice and firewood to residents. By 1882 he was operating a packet steamer between Quincy and Keokuk, Iowa, called the A M Jarrett. The boat was likely named after his wife, Anna M. Bywater. She also was an immigrant, born in Wales, who came with her parents to a farm near Ellington.

In March 1884, a newspaper mentioned James Jarrett as a candidate for mayor. The story, however, was about an altercation between Jarrett and Jerry Shay, city superintendent of public works.

Shay and his party had returned to Quincy from Burton, where they had been canvassing for votes.

They stopped at Charles Hildebrand's saloon at 20th and Broadway to "warm up."

Shay's group entered from 20th Street shortly before Jarrett walked through the Broadway entrance.

A difference of political opinion ensued, and Shay, being a much larger man than Jarrett, put him into a choke hold, whereupon Jarrett attempted to draw his pistol. Luckily, ex-city marshal John Kroener was present and ended the fracas.

The newspaper summed up the situation saying, "So ended the first skirmish of the approaching campaign."

Jarrett was elected mayor by a majority of 699 votes out of 3,841 total ballots cast. The mayor had a contentious year, and was not above using the power of his office in unofficial ways.

A month into his term, there were disagreements about the mayor's right to make appointments. One newspaper story began: "If Mayor Jarrett has started in to dig his own political grave, he has made a most brilliant beginning."

The mayor had proposed adding two African-American officers to the police force. The Journal found it ridiculous and wondered if the two would even allow their names to be put forth. Citing some recent saloon brawls, the conclusion was that a new officer… "would be killed so dead that nothing short of Gabriel's trump could resurrect him." The men were not appointed.

Among his first actions, the mayor outlawed the playing of ball on city streets and had an organ grinder removed who had set up shop along Front Street causing complaints by citizens unappreciative of his music.

In September 1884, Jarrett's steamer burned to the water line. It was a total loss and created another controversy.

Jarrett‘s statement of assets upon his election had listed the boat with a value of $400; however, he had it insured for $10,000.

There were immediate rumors of arson. Though the insurance company eventually paid the policy, some thought there should be charges of perjury against the mayor for falsifying an election document.

Such was the tenor of his time as mayor. Further irregularities involved charges by the local labor unions that he was not paying a fair wage, and upon one occasion Jarrett attempted to use his office to protect friends from arrest for attempted murder after a brawl.

After a one-year term, Jarrett was not re-elected. He next appears as Quincy harbor master, accused of taking all of the dock space for his wood barges and making passenger steamers unload farther north amid mud and coal piles.

James died unexpectedly on Aug. 7, 1892, leaving a widow and seven children. His son James Jr. followed his footsteps as an entrepreneur.

In 1901 he was awarded the bid to build a section of river levy near Fall Creek. In 1902 he was Quincy harbor master with no better results than his father.

Jarrett Jr. got a contract for cutting ice off the city dock, for which he promised to pay the regular labor union wage of $1.50 per day and sell ice for 35 cents per load.

He did not adhere to this, paying his workers $1 and selling the ice for 50 cents. Jarrett Jr. defended himself, saying the ice he cut did not come from the city dock off Front Street because that ice was half sand and the quality was too poor to sell.

During this time, his sister Susan Jarrett graduated from the University of Michigan medical school and began practicing in Quincy. Jarrett's orchards in West Quincy won awards from the Apple Growers' Association, and his other sisters moved in Quincy society.

On Feb. 24, 1915, when the Jarrett icehouse caught fire, the flames spread and burned wires off all of the poles of Quincy Gas Electric & Heating Co. between Maine and Jersey along Second Street. "Every city motor, every city street light and everything else dependent on city light or power was ‘Dead.' " It took hours to restore power.

How does this story connect to today? It serves as a reminder that our history affects our present.

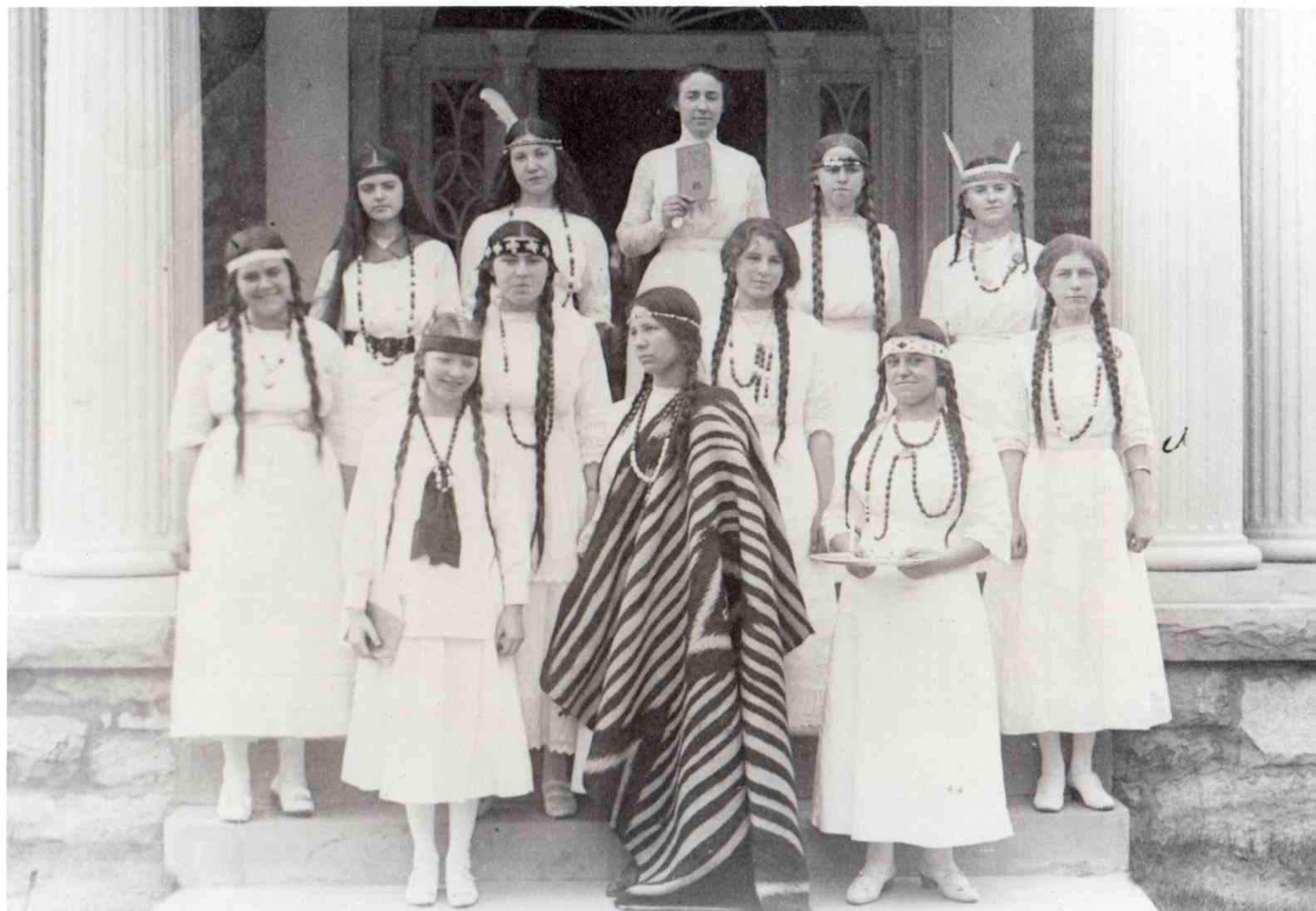

These illustrious Jarrett gentlemen were father and brother, respectively, to Agnes Jarrett Seymour, a most proper, severe and particular woman who married into a prominent family in Payson.

She always maintained her dignity, even when surrounded by Campfire Girls dressed as Indians.

Her surprised great-niece is the author of this article.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson. She is executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.