Meet Capt. Michael Piggott of Civil War fame

Even before the potato famine began in the mid-1840s, life in Ireland was a cruel existence of poverty, disease, and English oppression. Immigrating to America offered hope, and from 1820-1860 nearly two million Irish arrived, three quarters of these coming after 1845.

The earliest Irish emigrants came to work on the Erie, Illinois-Michigan, and other canal projects. With the coming of the railroads, they provided the labor to build the tracks.

In September 1841, Oan Piggott of Thurles, County Tipperary, Ireland, and his second wife and five children, landed at New Orleans. They soon headed upriver, settling in St. Louis. By 1850, St. Louis' population stood at 77,860, including 10,000 Irish. Poor and uneducated, the Irish toiled for low wages in the city's factories and along the riverfront. Oan's oldest son, William, worked as a mate on lower Mississippi River steamboats, while the second son, Michael, became a cabin boy. Both helped support the nearly indigent family.

Intent on having something to rely upon in the future, 16-year-old Michael, in 1850, "apprenticed himself to a bricklayer." When the apprenticeship finished in 1854, he came to Quincy and found work helping build "the original brick factory of the Collins Plow company." Eventually, Michael started his own construction business, building houses and other structures. He laid the brick for the four-story Occidental Hotel at 623 Hampshire Street.

Having entered the business world, Piggott realized he needed to fix a serious handicap or his future would be extremely difficult. The obstacle -- he was illiterate. Undaunted, Michael obtained books and taught himself "to spell, read and write."

On Nov. 4, 1856, Piggott married Eleanor Cannell, daughter of an early Quincy settler. The newly married and promising businessman saw all his dreams and hard work coming to fruition. But down the road, misfortune waited. Fulfilling an agreement to build a home, Michael "lost all that he had saved in the previous four years" when the other party went bankrupt. Setback, but not deterred, Michael continued at his trade. But in 1861, his life took another turn.

With the outbreak of Civil War in April 1861, Michael put his life on hold and enlisted in the Union army on Sept. 14, 1861. He did not sign up with any of the locally organized regiments, but joined what would become an elite fighting unit, Birge's Western Sharpshooters. Initially, the regiment was a pet scheme of Major Gen. John C. Fremont, who wanted an outfit made up of expert marksmen. Fremont set out to recruit men hailing from every state in the West. Also, before mustering in, each man had to pass a rigid shooting test. At a distance of 200 yards the shooter had to place three shots within three and one-third inches of the bull's eye. To further distinguish the regiment from others, Fremont had the men attired in "hunter's dress" and armed with the highly accurate Plains Rifle manufactured by St. Louis gunsmith, H. E. Dimick. The hunter's garb was soon replaced with regular uniforms, but the men held onto what became their signature sugar loaf hats -- decorated with three squirrel tails.

On Oct. 31, 1861, 27-year-old Michael Piggott, the brick mason from Quincy, was mustered into federal service at Benton Barracks near St. Louis. Pvt. Piggott was elected second lieutenant by the men in his company. However, before leaving for the field in December, he was promoted to first lieutenant.

The regiment left Benton Barrack in December and was assigned to the District of North Missouri commanded by Quincy resident Brigadier Gen. Benjamin Prentiss. At Mount Zion Church on Dec. 28, Piggott and Birge's Sharpshooters saw their first action.

By February 1862, the outfit was transferred to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's command and took part in the campaign to capture the Confederate forts of Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. Birge's men were an independent and unattached regiment temporarily assigned to Gen. Charles F. Smith's division. Smith did not know what to do with soldiers armed with deer rifles and no bayonets, but decided to let them fight as they saw fit. The Squirrel Tails scattered along the front and assumed the role of snipers, crawling within 50 yards of the rebel works; they picked off unsuspecting enemy artillerymen, silencing the rebel guns.

During the fighting of April 6-7 at Shiloh, the regiment was used as skirmishers. On April 14, 1862, the regiment was re-designated as the Western Sharpshooters, 14th Regiment Missouri Infantry. During the Union movement toward the rebel stronghold at Corinth, Miss., the Squirrel Tails were out in front of the army as skirmishers. On May 30, 1862, the rebels evacuated Corinth, and the Sharpshooters remained nearby undergoing reorganization under their new commander, Col. Patrick E. Burke. At this time Piggott was promoted by Missouri Gov. Hamilton R. Brown to captain of Company F.

In mid-September 1862, the rebels attempted to retake Corinth. During the fighting near Iuka, Miss., on Sept. 19, Capt. Michael Piggott commanded a makeshift battalion of skirmishers made up of Companies D, K, and F. The complete regiment fought in the two-day fight (October 3-4) known as the Second Battle of Corinth.

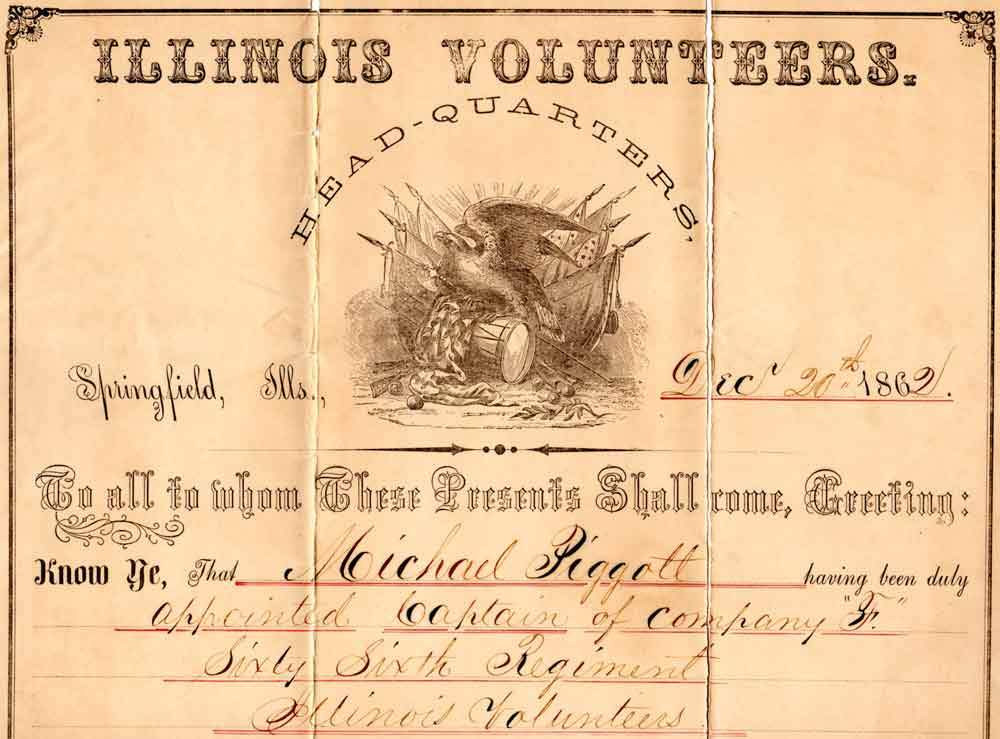

At the intervention of Illinois Gov. Richard Yates the Sharpshooters were transferred to Illinois service in December 1862 and renamed the 66th Illinois Volunteer Infantry (Western Sharpshooters). The regiment remained near Corinth, and Capt. Piggott penned a letter to the Quincy Whig Republican dated June 6, 1863. He wrote: "We have all the confidence in the world in Gen. Grant and the army he commands. We are a little dissatisfied on account of being put on garrison duty. Soldiers always prefer active service to that duty, but I am afraid we are doomed to remain here. ..."

Using their own funds, in the fall of 1863, 200 men of the Sharpshooters armed themselves with the Henry Repeating Rifles. The 16-shot rifle was a major firepower advantage over the muzzle loaders used by the rebels. Also, at this time the regiment was moved to Pulaski, Tenn., where 470 men re-enlisted. Capt. Michael Piggott was among those staying on to put down the rebellion.

In February 1864, Capt. Piggott returned to Quincy on recruiting duty. He set up shop at Pinkham Hall near Third and Maine. Broadsides were posted about town and notices ran in the local newspapers. About the Sharpshooters he wrote: "The regiment is used on the field to silence artillery and pick off officers." He added: "One of the Rifles belonging to the Regiment ... will be shown with pleasure to anyone wanting to see it."

Returning to the front, the 66th Illinois on May 9, 1864 "had the honor ... to open the fighting at Snake Creek Gap" and the campaign for Atlanta. By May 14, the rebels had been driven back to Resaca, Ga., where they entrenched. In an attempt to flank the enemy, Union troops tried to lay a pontoon bridge across the Oostanaula River at Lay's Ferry. Part of the 66th Illinois crossed the river in a canvass pontoon boat. In the operation Capt. Piggott was wounded. He later wrote: "While placing a pontoon bridge over the Oostanaula River near Resaca, Ga (on) May 14, 1864 (I) received (a) wound which caused (the) loss of right leg at knee and was mustered out by ... reason of disability January 19th 1865. ..."

Capt. Piggott returned to Quincy where he was a "potent factor in the councils of the Republican party. ..." In 1869, he was appointed Quincy's postmaster by President Grant and continued in that position until Grover Cleveland took office in 1885. With the election of McKinley in 1896, Piggott was made an Indian allotment agent in Kansas. He lived to age 86, dying on July 10, 1921, in his home at 1634 Vermont.

Phil Reyburn is a retired field representative for the Social Security Administration. He authored "Clear the Track: A History of the Eighty-ninth Illinois Volunteer Infantry, The Railroad Regiment" and co-edited "Jottings from Dixie: The Civil War Dispatches of Sergeant Major Stephen F. Fleharty, U.S.A ."

Sources

Eddy, Thomas M. The Patriotism of Illinois. Chicago, Clarke, 1866.

Atlas Map of Adams County, Illinois. Davenport, Iowa: Andreas Lyter and Company, 1872.

The Journal of the American Irish Historical Society, vol. 9, Providence, Rhode Island: Published by the Society, 1910.

The Journal of the American Irish Historical Society, vol. 19, New York, New York: Published by the Society, 1920.

Paul, Victor A. Roster of the Sharpshooters of the Army of the Tennessee. Obscure Place Publishing, 1997.

Piggott, Michael. American Genealogy. Quincy, Illinois, 1915.

Piggott, Michael. MS 920 File. Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois.

Redmond, Pat H. History of Quincy, and Its Men of Mark. Quincy, Illinois: Heirs & Russell, book and Job Printers, 1869.

Quincy Daily Whig Republican, June 27, 1863.

Quincy Whig-Journal, July 11, 1921.

Quincy Daily Herald, July 11, 1921.

The United States Biographical Dictionary and Portrait Gallery of Eminent and Self-made Men, Illinois Volume, American Biographical Publishing Co., 1876.