Minister's son proved to be good Samaritan

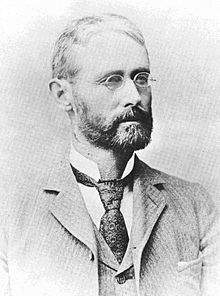

In 1837, Christopher S. Luce left Maine, came to Illinois, and settled in Adams County. The 29-year-old shoemaker arrived with his wife and two sons. The couple's third son, Moses Augustine, was born May 14, 1842, in Payson.

Ordained a Free Will Baptist minister in 1840, Luce also lectured locally on abolitionism. It could not be said that the Rev. Luce failed to practice what he preached, since in 1840 he purchased two lots in New Philadelphia, a town founded by Frank McWorter, a former slave and now a free black pioneer and entrepreneur. Luce was New Philadelphia's teacher and postmaster.

In 1848, McWorter, known as Free Frank, deeded a number of lots to Luce. The men had an agreement that Luce would build a seminary. The project never materialized, and Free Frank sued Luce. The ongoing dispute ended in 1853 when Luce sold out and left New Philadelphia, ending his 13-year tie to the community.

Moses Luce spent his early years in New Philadelphia, but three years after leaving the Pike County community, Christopher Luce enrolled his 14-year-old son in Hillsdale College preparatory school in Michigan. When the Civil War broke out, Moses, now 19 and still at college, enlisted with 12 fellow students in Company E, 4th Michigan Infantry.

The 4th Michigan left for Virginia on June 25 and was with the army at the first Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, but did not see action. A year later, during the Peninsula Campaign, the 4th was heavily engaged in the battles of Gaines' Mill and Malvern Hill in Virginia. Moses missed the battle in Fredericksburg, Va., but he was with the regiment at Chancellorsville, Va., and Gettysburg, Pa.

The Union campaign that kicked off in May 1864 was different. Overall command of the Army of the Potomac had been given to Ulysses S. Grant, a man not easily deterred. His initial movement into the Wilderness in Virginia was checked by Robert E. Lee's rebels. Rather than retreating to Washington, D.C., as his predecessors had done, Grant shifted the army to the left and renewed the fight. He informed President Abraham Lincoln: "I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer."

When Grant's offensive began, regiments such as the 4th Michigan Infantry found themselves in a difficult spot. They were nearing the end of their three-year enlistment, and many, but not all, thought they had fulfilled their duty. The 4th was down to a little over 100 men when the first battle of the Wilderness commenced. The fighting on May 5 and 6 took 12 more lives.

The night of May 7, Union troops marched away from the Wilderness battlefield toward the Spotsylvania Courthouse in an attempt to get around Lee's right flank. The wily Lee anticipated Grant's move, and the morning of May 8 dawned with the rebel army thwarting Grant's move. Grant attacked anyway.

Sgt. Moses A. Luce later explained: "The battle of Laurel Hill ... was in reality part of the battle of Spotsylvania ...." And, it "was a slight elevation situated in front of ... our army, and occupied by the Confederate army ...." The first light on May 10 found the opposing lines hidden by a heavy fog. For the work ahead this was a good omen. Since the morning, the 4th Michigan and the 22nd Massachusetts were to be the skirmishers leading the attacking blue infantry. With muskets unloaded and bayonets fixed, the men awaited the order to charge. Sgt. Luce recalled that as the men ran forward "a light wind suddenly broke the fog in front of us," leaving the men in the open. The enemy pickets and artillery immediately fired, but the skirmishers kept going and closed on the enemy's main breastworks. Now the rebel infantry suddenly rose and let go a volley. The charge collapsed, and the main column fell back in disorder. Of the seven men Sgt. Luce commanded that morning, five were dead or wounded.

Luce had taken cover in a ditch but realized that if he remained there he "would be taken prisoner, and the horrors of Andersonville were then pictured in dreadful detail." Fearing capture more than enemy bullets, Luce put it this way: "With all the speed I had I ran down the hillside and across the valley, under the fire of the enemy, and succeeded in reaching the first rifle pit of our pickets and leaped into it." One bullet had destroyed his rifle, and another grazed his forehead.

Hunkered down, Luce now heard the cries of Asher LaFleur, a Hillsdale College classmate and friend: "Luce! Luce, I am bleeding to death! I am bleeding to death!"

LaFleur's leg had been shattered. Not hesitating, Luce left the trench and ran back into the maelstrom of flying lead. He found LaFleur in a bad way; told him to get upon his back, and he would carry him. With LaFleur hanging on, Luce ran, dodging enemy fire until he reached the safety of the Union line.

LaFleur lived but lost his leg.

Having survived his three-year enlistment, Moses A. Luce was honorably discharged June 24, 1864. He returned to Hillsdale College, graduating in 1866. He then enrolled in the Albany Law School in New York, where William McKinley was a fellow student, and graduated in June 1867.

Luce next returned to Illinois and practiced law in Bushnell. After losing a bid for the state legislature, he moved to San Diego in 1873. Luce quickly became a prominent citizen and served over the years as a judge, postmaster, attorney for the Santa Fe Railroad, vice president of the California Southern Railroad and a partner in one of California's leading law firms. He died April 13, 1933.

Of his many achievements and accolades, none stand above the unselfish bravery he showed on May 10, 1864. For this action, he was awarded the Medal of Honor on Feb. 7, 1895. The citation reads that Moses Augustine Luce "voluntarily returned in the face of ... the enemy to the assistance of a wounded and helpless comrade, and carried him, at imminent peril, to a place of safety."

Phil Reyburn is a retired field representative for the Social Security Administration. He authored "Clear the Track: A History of the Eighty-ninth Illinois Volunteer Infantry, The Railroad Regiment" and co-edited "'Jottings from Dixie:' The Civil War Dispatches of Sergeant Major Stephen F. Fleharty, U.S.A."

Sources:

Batch, William C., A History of the Town of Industry, Franklin County, Maine. Farmington, Mass.: Press of Knowlton, McLeary & Co., 1893.

Bertera, Martin N. and Kim Crawford. The 4th Michigan Infantry in the Civil War. East Lansing, Mich.: Michigan State University Press, 2010.

Beyer, W.F. and Keydel, O.F., eds. Deeds of Valor: How America's Civil War Heroes Won the Congressional Medal of Honor. Stamford, Conn.: Longmeadow Press, 1992.

Brune, Evan. Hillsdale Collegian, "Heroes of Hillsdale." March 6, 2014.

Cannon, John. The San Diego Union-Tribune, "San Diego Civic Leader Earned honors in Civil War." May 26, 2016.

The Fresno Bee, "San Diego Pioneer Passes Away At 91," April 24, 1933.

McGrew, Clarence A. City of San Diego and San Diego County: The Birthplace of California, Vol. II. Chicago and New York: The American Historical Society, 1922.

Rhea, Gordon C. The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern, May 7-12, 1864. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 1997.

Rodman, Willoughby. History of the Bench and Bar of Southern California, 1909. Los Angeles: William Porter, 1909.

San Diego County, Calif: A Record of Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achievement. Illustrated, Vol. II. Chicago: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1913.

Sherwin, Doug. Daily Transcript, "Local Law Firm Still Going Strong After More Than a Century." Nov. 8, 2011.

Walker, Juliet E.K. Free Frank, A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier. Lexington, Ky.: The University of Kentucky Press, 2014.