Pioneer Trials: Mudslinging, slander, murder and mayhem

History is not always what it seems. It appears tidy with lists of names, dates and events, but upon closer inspection the neatness unravels. People had ambitions, agendas, dysfunctional families and even disreputable in-laws. The line between the good guys and the bad guys was movable. Southeast of Quincy where branches of prairie reach the bluffs in a beautiful area called Rolling Ridge, two murders occurred that illustrate this perfectly.

Daniel Lile, one of the first settlers in Adams County, arrived from Tennessee with his wife Sally, their son Henry and five other children about 1821. He built a cabin and later a horse-powered mill in the wilderness near Liberty when it was still part of Pike County.

The area was dangerous with four-footed and two-footed predators. Bears, wolves and cougars prowled the forest and by one estimate Indians outnumbered settlers twenty to one. The settlers were hard and sometimes dangerous men and at odds with one another on things like where the local government should be situated and whether Illinois should be a slave or a free state.

A series of disagreements in 1822-24 became known as the Great County Seat Wars, when control of economic development and judicial authority see-sawed between one settlement north of Alton called Coles Grove and a newer one called Atlas.

Future founder of Quincy, John Wood, was living near Atlas at this time. John Shaw, an elected state representative who in 1823 had been involved in an attempt to make Illinois a slave state, enlisted Daniel Lile in an effort to discredit the settlers of Atlas and keep the county seat in Coles Grove. Lile spread rumors throughout the area. The mudslinging concerned a tale in which John Wood, future governor of Illinois, supposedly admitted killing a convicted horse-thief while helping the sheriff transport the lawbreaker to jail. Details were murky, but the prisoner's body was found in a flooded creek.

In defense of his good name, Wood sued both Lile and Shaw for slander.

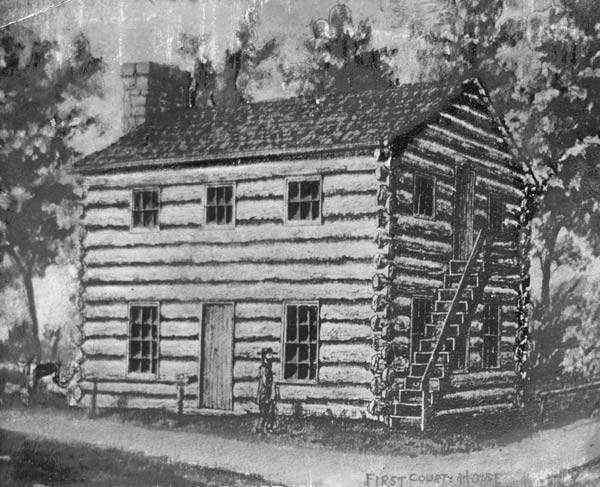

With fewer than 100 settlers, the scarcity of white men over 21 years of age (who were the only qualified voters), made it a challenge to fill any jury. In 1823 Lile had already served as a grand juror, but now he was outside the jury box. Actually, the jury had to deliberate under an oak tree, there being no room inside the courtroom.

At trial in 1824, Lile was found guilty of slander and fined. Shaw was astute enough to demand a change of venue. His trial was moved to another county and charges were later dropped. Lile was not so smart or lucky.

In the musical chairs game of defendant/victim/witness, Daniel Lile was called in 1825 as witness in an assault case against John Pettit and Thomas McCraney, for whom McCraney Creek near Richfield was named. Lile made a good witness, as he was also the victim. Court documents say "… James B. Pettite … did then and there beat, bruise, wound and ill treat to the great damage of said Daniel Lile to the evil example of all others …" No outcome was cited in this case.

In 1827 Wood packed up his family and went north to Galena to prospect for quick money in the lead fields. While he was away, his old opponent Daniel Lile was elected county commissioner. This county board authorized the construction of a courthouse and jail. It was a busy year for the Liles. Daniel's son, Henry, was a witness in an assault and battery case, and a perjury trial. Daniel was a witness in a case of unlawful assembly (a gathering of six or less) and another for ‘affray' (fighting between two individuals). Unlawful assembly seemed to apply to a gang of men preying on a weaker opponent.

In 1828 both father and son were defendants accused of assault; that April, Daniel had an ‘affray' with a different man and was fined $3 plus costs. In October Henry testified for the defense of a man accused of lying under oath in a previous trial where a married man had been accused of adultery.

By 1829 Daniel Lile had missed several court appearances and explained to the judge in a sort of ‘the-dog-ate-my-homework' vein that his failures to appear were because he was then living 300 miles away; he'd been sick; he was under a doctor's care; and he couldn't take care of his business.

Both Liles were also called again to answer unlawful assembly charges preferred by the same James Pettit accused of assaulting Lile earlier.

In 1830 Alexander Peterie arrived from Kentucky bringing his family, including sons, Andrew, John and Hiram and daughter, Elizabeth, who caught the eye of Henry Lile. Henry and Elizabeth were married that December. Another daughter, Sarah, also wed one John C. Johnson. The groom's middle initial would prove important.

In 1832 Lile/Peterie family relations got ugly. About four miles south of the village of Payson, near Pigeon Creek, John B. Johnson was stabbed and left to die. Daniel Lile swore to a judge that John Peterie, his brother Hiram and their father Andrew were the killers. The court determined that John Peterie was the murderer and dropped charges against the others. With his brother-in-law accused of murder by his father, Henry Lile was in an awkward position. He chose to sign as surety for brother-in-law Peterie's bond.

The granting of bond to an accused murderer was undoubtedly influenced by the fact that the jail authorized by then commissioner Lile was incapable of holding a prisoner. In 1832 repairs were approved for adding grates to the windows and fixing the leaky roof.

In 1833, with John still facing murder charges, his father and two brothers, along with Henry Lile, were back in court for threatening another settler. Eventually John Peterie was found guilty of manslaughter in the Johnson case and served ten years. His sister Elizabeth died about the time he was released from jail, severing the family bond with Henry Lile.

Daniel Lile continued to be in trouble until he finally disappeared from the record. He is thought to be buried near Richfield.

But Rolling Ridge wasn't finished with murder or the Peterie family.

In 1861 Ratcliff Harrison, a rum-maker living in a shanty near Pigeon Creek south of Payson was found bludgeoned to death. It was Andrew Peterie who saw the body and so became involved in a second murder trial, this time not as a defendant but as a prosecution witness.

Attison Cunningham and his nephew Nelson were both charged with murder. Nelson pled guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to ten years in prison, the same term John Peterie had served. Upon receiving his sentence, a relieved Nelson replied to the judge, "Much obliged." Attison Cunningham was found guilty, and hanged in the Quincy jail yard. Despite a jailhouse return to religion, Attison maintained to his final breath that he was innocent and his nephew Nelson had actually done the killing.

So, the next time you are faced with dry historical dates and names, remember our illustrious pioneers and know there's always more to the story.

Beth Lane is a member of the Historical Society and author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the true story of the Pfanschmidt murders. She recently moved here from Arizona where she was involved in the Society of Southwestern Authors, the Arizona Mystery Writers, and led writing workshops.

Sources:

Great River Genealogical Society, comp. Cemeteries of Adams County, Vol. 1. Quincy, IL: Great River Genealogical Society, 1988.

Kay, Jean. "The Rolling Ridge Neighborhood." Paper presented to the Great River Genealogical Society, Quincy, IL.

Murray, Williamson & Phelps, pub. The History of Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: Murray, Williamson & Phelps, 1879. A reproduction by Unigraphic, Inc. Evansville, Indiana.

Quincy Daily Herald. November 2, 1861 and August 18, 1893.

Quincy Morning Whig. Feb. 9, 1896 and August 10, 1898.

Quincy Whig Republican. November 16, 1861.

Robison, Stephen D. Early Records Index, Adams County, Ill, Vol. 4. Genealogical Society of Utah, contributor. Quincy: Great River Genealogical Society, 1993.

Thompson, Jess M. The Jess M. Thompson Pike County History, as printed in installments in the Pike Co. Republican, Pittsfield, Il. 1935-1939. (Chapters 1-6) Pittsfield, IL: Pike County Historical Society, 1967.

Tillson, John. History of Quincy. In Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois, William H. Collins and Cicero F. Perry, authors. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1905.

US Census Reports from 1810, 1820, 1830, 1840, 1850, 1860, 1870, & 1841. Tax records for Illinois: http://www.ancestry.com/ .