Prairie was site of Civil War camp, baseball, circus riot

When Quincy was a young city, it hugged the river. At 12th and Broadway, the countryside began. Across the cinder sidewalk and the dirt of Twelfth Street stretched a piece of land called Alstyne's Prairie. This parcel went all the way to 18th Street and north to Chestnut. It was undeveloped acreage cut by steep ravines and full of shade trees and prairie grasses.

The circus would set up its tent there. Civil War soldiers camped on the north part near where Quincy University is today. The prairie held the trees where at least two people were taken from the Quincy jail and lynched, and it was the site of the first regulation baseball game in Quincy.

About the only other building that far out of town was St. Mary Hospital on the south side of unpaved Broadway.

In 1866 the first regulation baseball game was held with equipment ordered from Chicago to ensure that appropriate bats, balls, etc., were used. The Quincy Daily Herald of April 26, 1923, reported that home plate was near the southeast corner of 13th and Vine, now renamed College, with first base to the west.

The prairie was not flat. The ground in front of home plate sloped west, while behind the plate it dipped to the northeast. There was no backstop. The newspaper reported that "small boys" were allowed by ground rules to help the catcher and gleefully chased down and returned balls to the diamond.

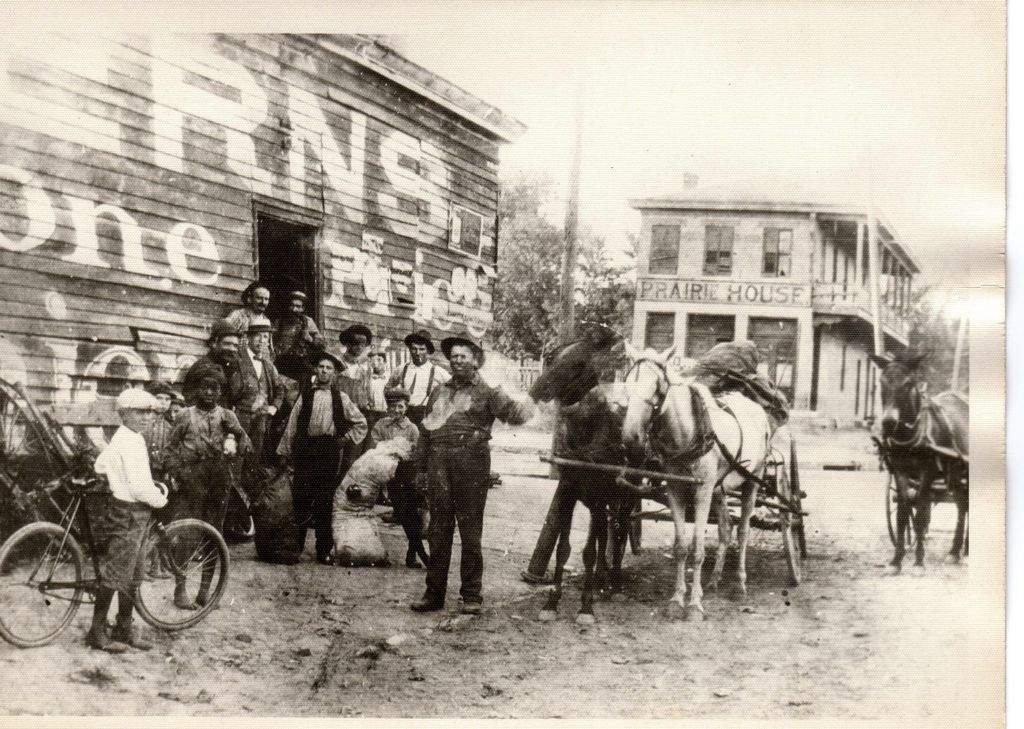

Cannoneer Peter Graff became custodian of the cannons for troops camped on Alstyne's Prairie and lived there. Graff learned his trade in Germany. During the Civil War, he "was drafted but on account of being minus several teeth, which were necessary to bite cartridges in those days, was excused," said an obituary in the Quincy Daily Journal on Dec. 21, 1894. Henceforth, any time the city of Quincy required a cannon blast for a celebration, Graff performed the duties. The Prairie House on the northwest corner of 12th and Broadway was the first city business to greet visitors from the north and east. It had a well and a large pump out front to water horses, cattle or elephants if the circus was in town. The two-story brick building featured a general store and a barroom, along with meeting rooms. Upstairs were rooms for rent, frequently occupied by country folk and theater people in town to give performances. The Prairie House in February 1866 purchased 800 tons of ice from local ice cutters to be stored for use during the year to come. It was a busy place.

At one time the Prairie House was known as a "Dance House" and according to the Quincy Whig of May 29, 1869, "the scene of midnight frolics for months past, much to the annoyance of peaceable citizens in that vicinity." The police raided the festivities and rousted by their estimation 300 to 400 men and women. They managed to arrest 30 of the revelers. The rest "came pell mell, through windows, carrying sashes and blinds with them, over porches, any way to get out."

On July 6, 1874, the International Circus was in town, its tent pitched on Alstyne's Prairie. During one performance, two circus employees entered in a dispute. One was taken to the city jail but released. It was not known if he was a circus employee. After the big top show was over, the two renewed the disagreement in the Prairie House saloon. The fight came to the attention of a Quincy policeman, Officer Dallas, who ordered them to stop. Dallas was the first Quincy black police officer, and the circus roustabouts did not recognize that he was an officer of the law.

They resented the outside interference, and the two set upon him. Dallas drew his weapon and fired without hitting anyone. The crowd turned on the officer, who sensibly ran out of the building blowing his whistle to alert other nearby officers. Dallas escaped by hiding in some dense bushes while the crowd milled about. A second officer heard the whistle and the crowd of men shouting about killing someone and raised an alarm. Meanwhile the two quarreling men were taken by the chief roustabout back to where the circus was packing up to leave.

By the time the alarm reached downtown police headquarters, according to the July 9, 1847, Quincy Whig, it had become a "riot alarm" complete with reports that the circus force was terrorizing the town, killing scores of people and "the streets were flowing rivers of blood." Soon police were seen reporting at the station, and two were dispatched to rouse the National Guard. Mayor Frederick Rearick asked the commander to open the armory and hand out weapons to the guard and other citizens. Fifty guns were brought out.

The armed force marched to the levee to stop the circus before it was determined that the circus had not moved from its grounds. The march was changed to Twelfth Street. Jacob Metz, chief of police, ordered the ferries into the river so the circus could not sneak out and escape.

By the time the company marched up Broadway, it was met at Seventh Street by Mr. Bailey, one of the circus proprietors. He appeared hastily dressed and uninformed about the ruckus. The mayor wanted to arrest the entire circus. Mr. Bailey demurred and countered with an offer to deliver any and all of his employees who were involved. This was deemed acceptable, and the march continued. Just before reaching Twelfth Street, Mayor Rearick stopped the procession again to address them. He reminded them that they were "peaceable citizens called out to maintain the majesty of the law and counseling them to go on the battle field coolly and courageously, to refrain from excitement and to do no violence unless violence becomes a necessity." Eventually nine men were arrested, fines were paid, two were held for trial, and so ended the great circus riot in Quincy.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson. She is former executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

"Former Pioneer died at St. Joe," Quincy Daily Whig, May 15, 1920, p. 5.

"Old Reporter Lights His Pipe," Quincy Daily Herald, April 26, 1923, p. 6.

"Peter Graff Passed Away," Quincy Daily Journal, Dec. 21, 1894, p. 4.

"Raid on a Dance House," Quincy Whig, May 29, 1869, p. 4.

Scenes from Way Back When the Prairie House at 12th and Broadway was Quincy Outpost," Quincy Daily Herald, July 26, 1925, p. 3.

"The Night of Circus Riot," Quincy Daily Whig, Feb. 21, 1902, p. 2.

"War's Dread Alarm," Quincy Whig, July 9, 1874, p. 3.

"Whig & Republican City Matters," Quincy Daily Whig, Feb. 7, 1866, p. 4.