President Lincoln Fills a Supreme Court Vacancy

On October 15, 1864, the Quincy Daily Whig informed readers that, “Washington dispatches of the 13th have just reached us announcing the death of” Roger B. Taney, Chief Justice of the United States, at age 87. Election Day was November 8, and President Abraham Lincoln was standing for reelection. Adams County, with the nation, awaited news of what action, if any, he would take to nominate Taney’s successor.

Taney, appointed chief justice by President Andrew Jackson, had served on the Court since 1836. Readers probably associated him most closely with his majority opinion in the Dred Scott case of 1857, a decision denounced by the Whig. Taney had articulated two controversial holdings: first, the very offensive statement that a slave could never be recognized as a citizen entitled to petition a federal court for his freedom and, second, that Congress lacked the constitutional authority to prohibit slavery in territories not yet admitted as states (such as Kansas and Nebraska).

On March 31, 1857 the Quincy Daily Whig , commenting on the decision, had condemned the “slavery oligarchy” which “has its hand now upon the Government from the highest to its lowest official. All men do its behest.” When Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas debated in Quincy on October 13, 1858, Lincoln had expressed his party’s criticism of the decision: “We do not propose to be bound by it as a political rule in that way, because we think it lays the foundation not merely of enlarging and spreading out what we consider an evil, but it lays the foundation for spreading that evil into the States themselves. We propose so resisting it as to have it reversed if we can, and a new judicial rule established upon this subject.”

Taney and Lincoln met on March 4, 1861 as the chief justice administered the constitutional oath to the new president. Certainly Taney knew that Lincoln was referring to the Dred Scott case when the president said in his Inaugural Address that the “candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”

In short, Lincoln told Taney and all those present, the Court’s decision had expropriated legislative/executive powers to establish public policy, which the Constitution had invested exclusively in Congress and the Presidency.

Within weeks Lincoln and Taney clashed. Opponents of Lincoln in Maryland were impeding movement of Union troops by blowing up railroad bridges. Lincoln suspended the constitutional right to a writ of habeas corpus and authorized Army commanders to arrest and imprison saboteurs. The lawyers for one detainee, John Merryman, in a questionable tactic, applied directly to Taney in Washington, requesting him to order that the military justify its confinement of their client.

On May 27, 1861, the Quincy Daily Whig reported that, “John Merryman, a wealthy and respectable citizen of Baltimore County, was arrested last night by Government officers, charged with burning the bridges on the North Central Road. He was taken to Fort McHenry. It is understood he acted by authority of the Mayor and police commissioner.”

Taney conducted a hearing in Baltimore, then, acting without the other Supreme Court justices, eventually ordered the Army to bring Merryman to a court hearing. Lincoln ignored the order, and the military continued to hold Merryman for about six weeks. A civilian grand jury indicted him for treason, but he posted bail and Taney refused to set his criminal case for trial. Merryman suffered no further legal consequences.

With Taney’s death, Lincoln had an extraordinary opportunity. By April, 1863 he had appointed Noah Swayne, Samuel Miller, David Davis of Bloomington Illinois, and Stephen Field to the Court. Taney’s vacant position allowed Lincoln not only to appoint a fifth jurist (and the last needed to assure a Lincoln majority on the nine-member bench), but also to name a new chief justice whose authority could change the direction of a tribunal dominated by almost thirty years of appointees chosen by Democratic presidents. As a former Whig and the first Republican president, Lincoln surely understood the political significance of this moment.

Lincoln, however, was more than a masterful politician. In his Illinois legal practice, he had been one of the best constitutional lawyers in the United States. Perhaps, like the Quincy Daily Whig , he recognized some merit in Taney’s earlier work. When illness threatened Taney’s life in 1855, the paper had republished a New York dispatch saying, “Under the most favorable circumstances, in the nature of things, that his connection with the Supreme Court cannot be very prolonged; but come when the separation may, it will be attended with deep regret by the public, and by a sense of serious loss to the highest tribunal know to our laws.”

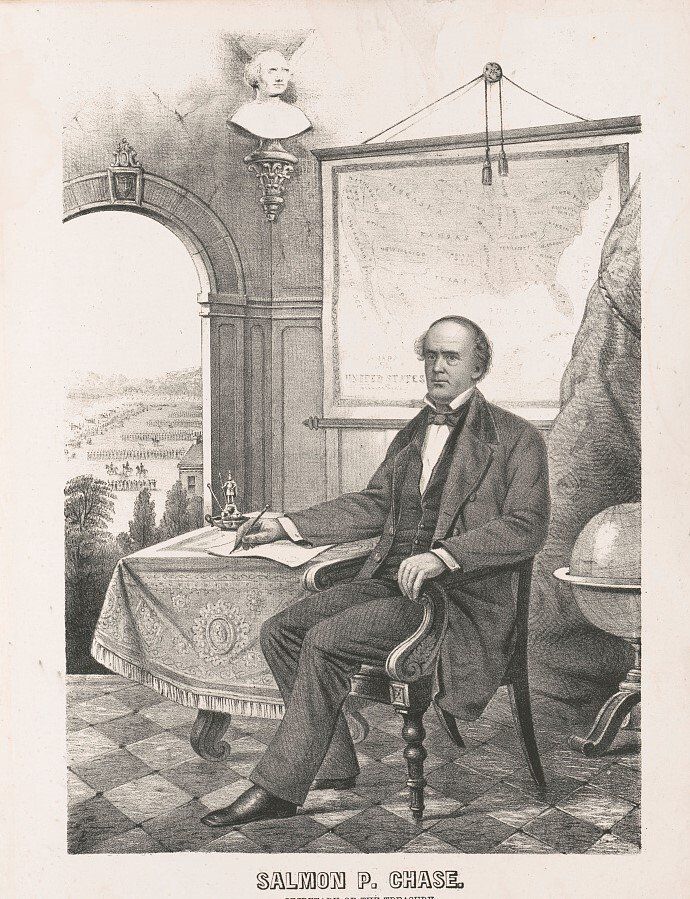

Lincoln refrained from naming Taney’s successor in the 28 days before Election Day. In the Electoral College, Lincoln carried every state except Kentucky and Delaware. On December 6, 1864, he nominated a former political rival and esteemed ally of abolitionists and of the Radical Republicans who had long considered Lincoln too cautious, Salmon P. Chase. The Senate confirmed Chase the same day. (Regular Senate Judiciary Committee hearings before a Senate vote on Supreme Court nominees did not begin until 1955)

As Chief Justice, Chase presided over the Senate impeachment trial of Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, who escaped conviction and removal from office by one vote. By ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865, the United States abolished slavery and declared that all persons born in this country, without exception, were citizens, thereby nullifying Taney’s ruling in the Dred Scott case.

SOURCES

Basler, Roy P., editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, “ Sixth Debate with Stephen A. Douglas, at Quincy Illinois ”, III, pp.245, 255 (1953).

Basler, Roy P., editor, ibid., “First Inaugural Address—Final Text, March 4, 1861,” IV, 262–71.

“By Telegraph—Morning Dispaches—From Baltimore”, Quincy Daily Whig , May 27, 1861, p. 2

“Death of Chief Justice Taney”, Quincy Daily Whig , October 15, 1864, p. 2.

“Illness of Chief Justice Taney”, Quincy Daily Whig , December 31, 1855, p. 2.

“Perversion of Truth”, Quincy Daily Whig, March 31, 1857, p.2.

Scott v. Sandford , 60 U.S. 393 (1857); (the name of the respondent owner of Dred Scott was misspelled by the Court reporter and should have been “Sanford”.)

Stone, Geoffrey R., “Understanding Supreme Court Confirmations”, The Supreme Court Review, (January 2011), pp. 381-467