Quincy Anti-Slavery Voices in 1839: American Slavery As It Is

Slavery’s enemies were organizing fervently by the 1830’s. As the nation expanded American abolitionists followed, from New England to southern states, and to the slave state of Missouri. Citizens, including early Quincyans who contributed to this antebellum brand of citizen activism united to fight slavery’s extension. The emancipation movement in Illinois took root in Quincy and Adams County, where citizens in 1835 formed an anti-slavery society, attended the first Anti-Slavery Convention in Alton in 1837, and at the same time began what would become an active Underground Railroad.

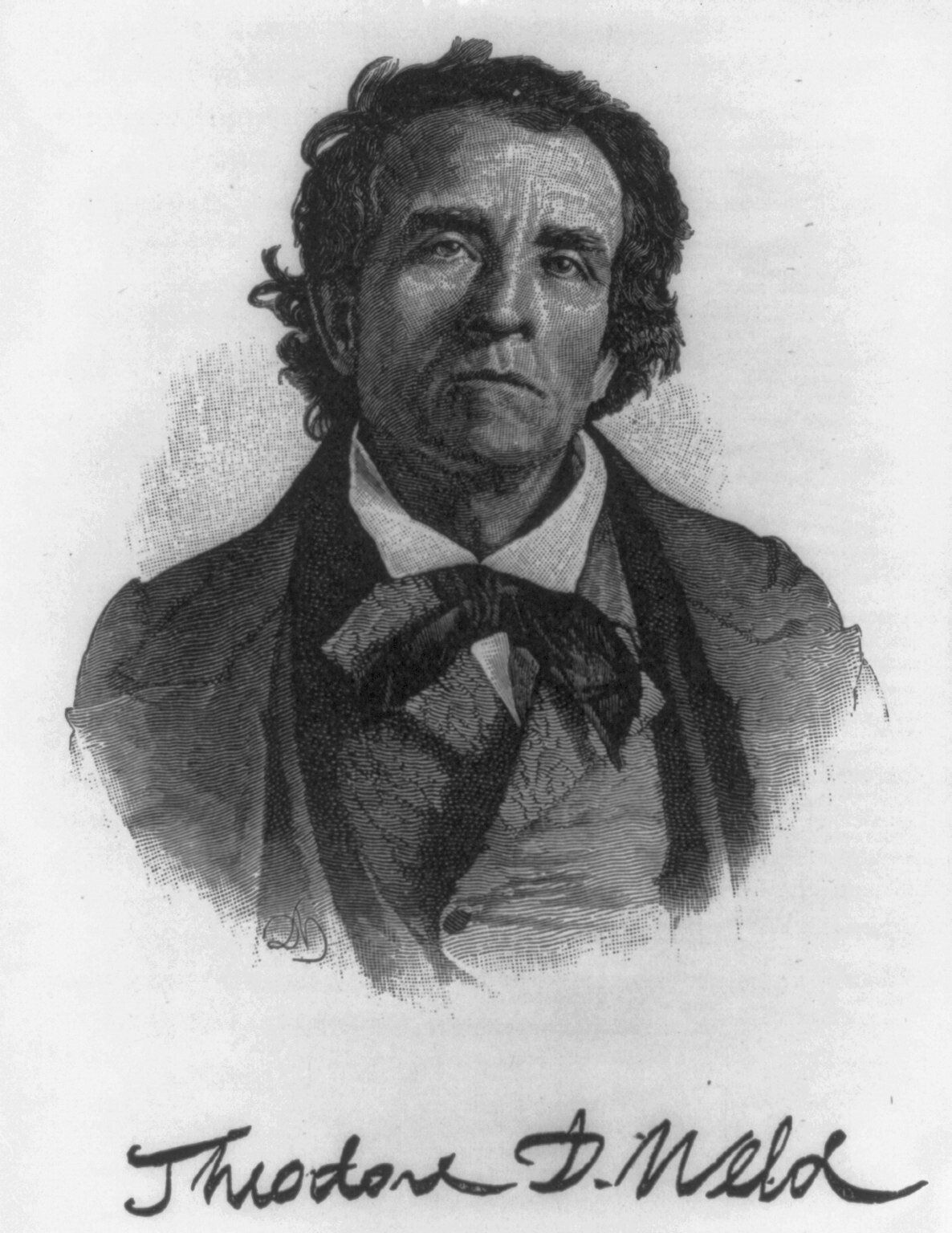

The American Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1835 at Oberlin College by Theodore Dwight Weld, Arthur Tappan, and others. In 1839, the Society published American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses. With his wife, Angelina, and her sister, Sarah Grimke, Weld organized the narrative. It remains the lengthiest abolitionist publication in U.S. history. Weld would become an ally and friend of Frederick Douglass, who at the time they were compiling the book, was still enslaved in Maryland.

The narrative was published in 1839, two years after the Illinois Anti-slavery Convention in Alton. The goal of the publication was to influence readers who were not familiar with the evils of slavery and were told that a ‘mild slavery’ was beneficial to the enslaved. It described the powerless conditions of nearly three million men, women, and children. The meticulous documentation broadened the public knowledge about slavery conditions. There were a number of Quincyans who contributed to the book.

The Welds and Sarah Grimke scoured thousands of southern newspapers to gather evidence to combat pro-slavery arguments, many times from active and former slaveowners’ own words. Runaway slave bulletins and personal narratives from southerners and visitors to slave states were included in the investigation for the publication. They were trying to combat slaveowner’s goals of keeping not only their human property ignorant, but free Americans as well. Personal slave narratives detailed a single person’s experience, but “American Slavery As It Is” described the overall conditions of slaves across all the states.

Quincy attracted many antislavery Americans, and their association with Weld and the Grimke sisters connected them to the most ardent advocates of freedom in the U.S. The goal was to ‘generate a condemnation of slavery from both those who observed it and those who perpetuated it.’

Dr. David Nelson was an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society in Missouri, a slave state. In 1836 he was chased out of Missouri for his antislavery views and fled to Quincy. There he founded The Mission Institute, which trained young men and women as missionaries and opponents of slavery. Practicing as a physician, Nelson was converted to the abolition’s cause by a speech by Theodore Weld in St. Louis. The speech influenced Nelson to leave medicine and become a Presbyterian minister. As Weld had converted Nelson, Nelson converted a school teacher named Elijah Parish Lovejoy to the ministry and abolitionism. Nelson was an outspoken abolitionist until his death in 1844.

Nelson wrote of an incident “that came under my observation as a family physician.” He described the moment he saw the mistress of the house thrust her servant girl’s hand into scalding water as punishment for a trifling offense.

Charles Renshaw preached for Quincy Congregational Church from July 1838 to February 1839. He knew Weld personally and they both were members of “Lane Rebels,” a group of seventy students expelled from Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio, for organizing an anti-slavery debate. Weld was the leader of this group of students and inspired many abolitionists to spread their message of freedom.

Renshaw wrote personal letters to Weld at his New York City headquarters after they parted. Before coming to Quincy, Renshaw graduated from Oberlin College in Ohio and married a fellow student. He was an anti-slavery agent for several years, and then moved to Jamaica with his wife for missionary work.

As a southerner, Renshaw relayed an experience he had while living in Kentucky: “In a conversation with Mr. Robert Willis, he told me his negro girl had run away from him. He was convinced she was lurking around, and he watched for her. He soon found her…got a rope, and tied her hands across each other, then threw the rope over a beam in the kitchen and hoisted her up by the wrists. He said, “I whipped her til the lint flew I tell you.’ I asked him the meaning of making the lint fly, and he replied, ‘til the blood flew.”

Renshaw sent Weld a letter he received in Quincy dated January 1, 1839 in which the letter’s author accused neighboring Missouri slave owners of brutality. Fearing retribution, Renshaw did not reveal the author’s name but added notes from Henry H. Snow a Quincy judge and Willard Keyes, a founder of Quincy, who testified to the author’s character.

Snow was an early Quincy settler, its first postmaster, president of the anti-slavery society in Quincy and served as a court clerk, and later a judge. He was a member of Asa Turner’s abolitionist church, the Congregational Church at Fourth and Jersey Streets.

Keyes and Snow were solidly anti-slavery Americans. Keyes attended the 1837 Illinois Anti-Slavery Convention, was a member of the fledgling Adams County Anti-Slavery Society and was a trustee for Nelson’s Mission Institute. He was also an Illinois agent for the abolitionist paper “The Philanthropist” from Cincinnati, Ohio.

“American Slavery As It Is” sold 100,000 copies in its first year of publication. Theodore Weld relied on the horrifying aspects of slavery to emphasize its need for destruction. A fellow ‘Lane Rebel’ and graduate of Oberlin College, James Thome, visited the West Indies after the slaves were emancipated there and wrote, Emancipation in the West Indies. He was profoundly moved by reading the Welds and Grimke book and described his experience with it: “I have waded through the blood and gore of ‘Slavery As It Is,’ and have just come out on the other side dripping, dripping…”

Heather Bangert is involved with several local history projects. She is a member of Friends of the Log Cabins, has given tours at Woodland Cemetery and John Wood Mansion, and is an archeological field/lab technician.

Sources

Barnes, Gilbert, and Dwight L. Dumond, eds. Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld,

Angelina Grimke Weld, and Sarah Grimke, 1822-1844. 2 vols. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1965.

Carter, William, and S. Hopkins Emery. A memorial of the Congregational Ministers and

Churches of the Illinois Association. Quincy, IL: Steam Power Press, 1863.

The Oberlin Sanctuary Project. The Lane Rebels and Early Anti-Slavery at Oberlin.

The Lane Rebels and Early Anti-Slavery at Oberlin (oberlincollegelibrary.org)

Quincy City Directory. Quincy, IL: Dr. S. J. Ware, 1848.

Weld, Theodore Dwight. American Slavery As It Is: Testimony Of A Thousand

Witnesses. New York: American Antislavery Society, 1839.