Quincy area land bounty pays volunteer soldiers

Early settlement in Quincy and Western Illinois was closely tied to land bounties the U.S. Congress awarded to volunteer soldiers in the War of 1812. It was a method of compensation that avoided menacing questions over the role and size of government.

Until President Lincoln’s time, the nation’s statesmen predominantly regarded a standing army as a threat to liberty. It was no small question for those who nursed the nation after its birth through infancy. Even ignoring concerns that a standing army would mean higher taxes and bigger government, how would an army function? The Constitution made the president the commander in chief. But could he control an army? And could he be controlled?

The founders simplified the matter by continuing the practice of British governors of the American colonies. When soldiers were needed, the executive called for volunteers — mostly militiamen. As an incentive to service and loyalty, the founders also continued the practice of awarding bounty land to the volunteers.

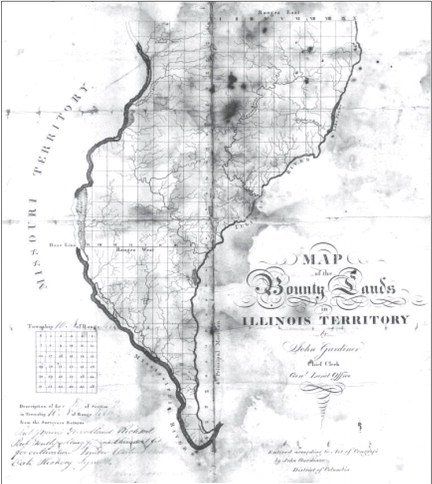

So it was in 1811 when a second war with Great Britain appeared imminent. Congress awarded each veteran (or his heirs) of the War of 1812 three months pay and a quarter section (160 acres) of land. These parcels of land totaling 5.36 million acres were situated in a wedge between the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers and extending to the northern border of today’s Mercer County.

Among the treasures of the Historical Society are 15 original “land patent titles,” or “patents” to the War of 1812 bounty lands in this huge Illinois Military Tract. Each patent carries the official seal of the U.S. General Land Office.

The patents do not indicate whether the men who held them were soldiers during the War of 1812. Veterans who received the bounty land grants were given warrants for them. A veteran could exercise his warrant and receive a patent, or title, for the land, or he could sell it. Since most veterans had established homesteads and families in the east or south, they had little interest in moving to a primitive west. Many sold or exchanged their grants and patents were issued to someone other than the veteran.

Quincy founder John Wood, for example, was the fifth owner of the 160 acres he bought between the Mississippi River and what roughly are 24th Street and Kentucky and Madison streets in today’s Quincy. Wood bought his parcel on November 19, 1822, from Peter Flinn. Flinn was not happy with the fire sale price of $60 Wood paid for it, but he needed to raise money to bring his family from Ireland. The land grant for the property Wood acquired was owned originally by one Mark McGowan, a veteran of the War of 1812, who sold it in late 1817 to a Francis Koran. Koran sold it to Flinn on April 3, 1819.

Many veterans lost their land inadvertently, unaware that the law admitting Illinois into the Union in 1818 allowed the state to tax bounty land three years after the patent was issued. Theodore Carlson in his book, The Illinois Military Tract, wrote that there was an “erroneous impression ... in the Eastern states that the military lands, similar to other public lands, were exempt from taxes for five years from date of patent.”

Speculators could buy properties for the amount of tax owed. With the tax at one-half of one percent of the land’s value, the tax on 160 acres was as little as $10. The owner had a year to redeem his property at the price the speculator paid, plus a penalty of 100 percent, or lose his land.

Wood and Quincy co-founder Willard Keyes attended the first tax sale at the state capital in Vandalia in December 1823 and bought several lots near Quincy. In his comprehensive “History of the City of Quincy, Illinois” Col. John Tillson wrote that Wood hoped to obtain “the other title if their tax purchase was not redeemed.”

Keyes at the Vandalia sale bought 80 acres of land for taxes and costs of $11. Little more than a year later, with no redemption, Keyes became the owner of everything north of Broadway and west of 12th Street in today’s Quincy.

Chance in early 1820 had brought Wood and Keyes together in the federal land office in Edwardsville. Each had spent two years at their previous residences, Wood, a New Yorker, trying his hand at farming in the Ohio Valley and Keyes, who was from Vermont, teaching French and Indian children at Prairie du Chien, Wis.

They teamed up as small-scale speculators and made their way to Pike County where they squatted (resided on land they did not own), farmed and corresponded with “owners of soldiers’ patents in various parts of the country ... to hunt up quarter sections for different owners, at the very moderate price of one dollar per day,” according to Keyes. That’s how Wood met Flinn, who thought his land was “too far off from civilization.”

Acting originally as an agent for Dr. Benjamin Shurtleff of Boston, John Tillson, a Halifax, Massachusetts, native — and father of the historian by the same name, began buying land in 1819 and surveying, perfecting titles and paying taxes for absentee owners. Speculating himself, Tillson built one of the state’s largest land companies. In 1835 alone he bought 695 parcels totaling 111,200 acres at an average price of $1.21 per acre and sold only 12 at $1.52 per acre. He became the second largest landholder in Illinois, owning more than 420,000 acres. In 1836 the federal land office at Quincy recorded sales of 569,376 acres, the highest of the 10 land offices in Illinois.

Tillson moved to locations close to properties in which he was dealing, which brought him in 1843 to Quincy, where he diversifi ed his business interests, investing $100,000 in the Quincy House Hotel on the southeast corner of Fourth and Maine streets.

In his book Carlson estimated that by the time speculators paid for land purchases and taxes, profits were small. That was not true for all speculators. Land speculation built a fortune for Wood and Tillson, who would lose them, and for Keyes. It enriched Stephen B. Munn of New York. In one month in 1835, Munn bought 1,992 acres in 21 parcels of Adams County land for $1.25 per acre and sold them the next year for $2.13. The Historical Society owns one of Munn’s patents.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

Carlson, Theodore L. The Illinois Military Tract. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1951.

Davis, James E. Frontier Illinois. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Illinois State Archives. "Illinois Public Domain Land Tract Sales Database." http://www.ilsos.gov/isa/landSalesSearch.do

"Land Grant Patent, David Paul; Deed, David Paul to Benjamin Shurtleff," Map Case 1, D45, Historical Society.

"Land Grant Patent, Stephen B. Munn," Map Case 1, D76, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Park, Siyoung. "Land Speculation in Western Illinois: Pike County, 1821-1835." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society." Summer 1984.

Strange, A.T. "John Tillson." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 17, 1925.

Tillson, Colonel John. "History of the City of Quincy." In William H. Collins and Cicero F. Perry. Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.