Quincy City Physicians

Dr. Baker was the first doctor to arrive in the Quincy area 1824. He did not stay long. At that time, there were less than 100 settlers in a range of 30 miles. Various other physicians came and went in what was known as Bluffs, renamed Quincy in 1825.

Dr. Joseph N. Ralston arrived in 1832 and with Dr. Samuel W. Rogers, helped Quincy survive the Cholera epidemic in 1833. As the community began to grow, the city council decided they needed a city physician to care for the newcomers and the indigent. As a river town, people arrived with every riverboat. Around 1200 riverboats were on the Mississippi by the 1830s with thousands more to come.

The earliest newspaper reference to a city physician was in 1847 when Dr. Louis Watson was elected to the position by the city council in April. His salary was fixed at $100 per year.

Historically, the term city physician comes from the middle ages in Germany. The physician was hired by the city council and was to care for the poor, while looking out for the health and sanitation of the community.

A small article in the February 15, 1849, Quincy Herald mentioned small pox. The paper had been informed previously but was not sure of the veracity of the report so said nothing. But by this date decided that the citizens should go to the city physician for the inoculation to prevent the disease saying, “… it is advisable that the immediate benefits of this popular preventive be secured.” By then, two people had died and three other cases were known.

Also in 1849, Cholera returned to Quincy, thought to have come from immigrants or disembarking passengers on the riverboats. The city council passed an ordinance that all passengers had to be examined by the city physician before allowed into the city. A committee was appointed to find a place for the passengers. After “… examination, and purification, as their condition and the exigencies of the case may require, …” they were given a certificate which allowed them into the city. Unfortunately, that process did not stop Cholera and the disease lingered four months resulting in the deaths of 286 citizens.

The Quincy papers continued to report the yearly election of the city physician by the city council. Dr. W. D. Rood was elected in 1852 and in 1853, his salary was $150 per year. Occasionally more than one physician was nominated for the position and in 1854, it took three ballots for Dr. Louis Watson to defeat Dr. Rood.

Very little was ever reported about what the city physicians actually did. In theory, he was to work on sanitation, disease prevention, care of the poor, and screening of new arrivals for diseases. Occasionally there would be an ordinance prohibiting sick people from entering the city as there was in 1849. How that was monitored is a mystery as The rise and fall of disease in Illinois described Quincy as a “… stormy, seething mob. It was the frontier, the jumping off place. Gunmen and gamblers, rough people of every sort…”

Vaccinations were a large part of the job. The city put an ad in The Quincy Daily Whig, June 23, 1857 which said, “The city Physician, Dr. F. B. Leach, will vaccinate, as preventative against Small Pox, all applicants that call on him at his office on Fourth, between Hampshire and Vermont streets on all days of the week, (Sundays excepted) between the hours of 2 and 4 o’clock pm at the expense of the city.”

Small Pox was a persistent communicable disease. That same year another ordinance demanded that the heads of the household in the city or within 5 miles of the city, post a sign on their door barring admittance to all if “any person is sick or infected with the Small Pox … ‘Sickness- No Admittance,’ either printed or written in large letters to be posted up in the most conspicuous place on the front of such dwelling or house and to maintain and keep such notice posted there until in the opinion of the City Physician such notice may be safely discontinued.” The council also established a fine for not posting a sign or taking it down.

Interestingly, by the late 1850s the position of the city physician became political. Alderman would nominate a doctor and there might be more than one candidate for the council to vote on. In 1858, the two candidates were Dr. F. B. Leach and Dr. Ochlman. Dr. Leach won. Both of the doctors were again nominated in 1859, “subject to the declaration of the Democratic City Convention.” In the official record of the vote, Dr. Ochlman is listed as an Independent, with 458 votes. Dr. Leach is listed as a Democrat, with 832 votes.

In October of 1871, a drunk died in the city jail and the city physician, Dr. Bryan Baker, was chastised for not attending to him. He resigned in December 1871 and moved to Kansas. Dr. Platt was appointed. The October 17, 1871 Daily Quincy Herald said, “ Dr. Platt is a competent physician, and will give the poor prompt attention. His office will be at the city building.”

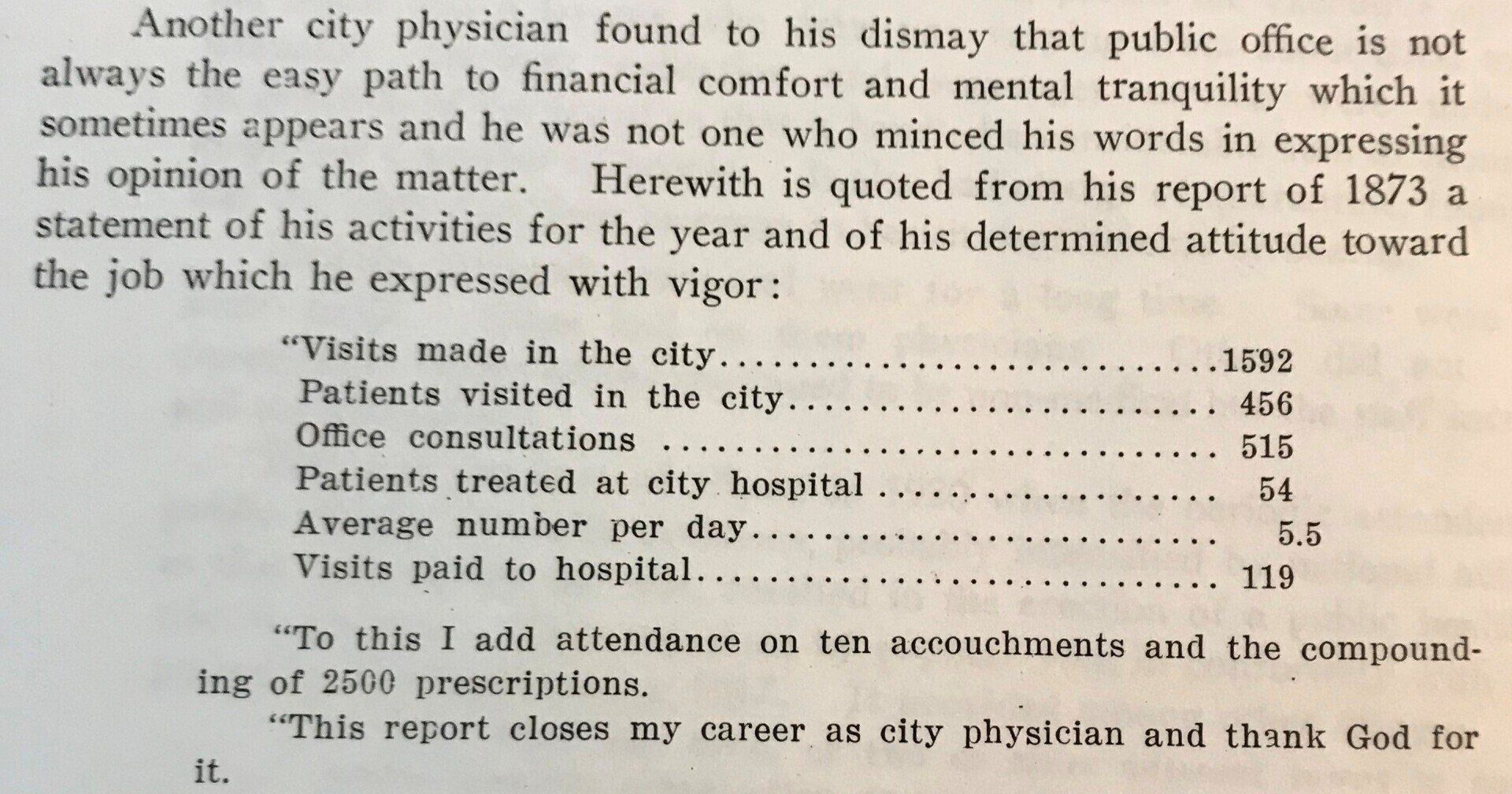

Dr. Platt gave 604 vaccinations his first year and established city dispensaries which helped the indigent sick and saved the city money by purchasing drugs wholesale. Pay was still poor and in 1873, Dr. Samuel A. Amery, the city physician, resigned and said, “I congratulate myself upon my release from such a public burden at such an insignificant salary, six hundred dollars per annum.” He went on to castigate the city council for their inconsistencies in salary with the city sexton who buried Small Pox victims getting double pay but not the physician who cared for them. He then listed his activities for the year some of which were 1592 patient visits, 515 office consultations, 119 hospital visits, and 2500 prescriptions compounded.

Arlis Dittmer is a retired health science librarian and current president of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County. During her years with Blessing Health System, she became interested in medical and nursing history—both topics frequently overlooked in history.

Sources

“Appointed.” Daily Quincy Herald, October 17, 1871.

“Candidates Department.” Quincy Daily Herald, April 4, 1859, 2.

“The City Council.” Quincy Whig April 28, 1847,2.

“City Council.” Quincy Whig, June 16, 1847, 3.

“City Council.” Quincy Whig, July 17, 1849, 1.

“City Council.” Quincy Whig, April 18, 1853, 2.

“City Council.” Quincy Whig, April 25, 1854.

“City Physician.” Quincy Daily Whig, June 23, 1857.

“Council Proceedings.” Quincy Daily Whig and Republican, April 29, 1858, 3.

“Official Vote Of The City Wards.” Quincy Daily Herald, April 20, 1859, 2.

Rawlings, I.D., M.D. The rise and fall of disease in Illinois, Volume II. Springfield, IL: The State Department of

Public Health, 1927.

“Small Pox.” Quincy Herald, February 16, 1849, 3.

“Small Pox.” [ad] Quincy Daily Whig, October, 13, 1857, 2.