Quincy great debate featured weary Lincoln, Douglas

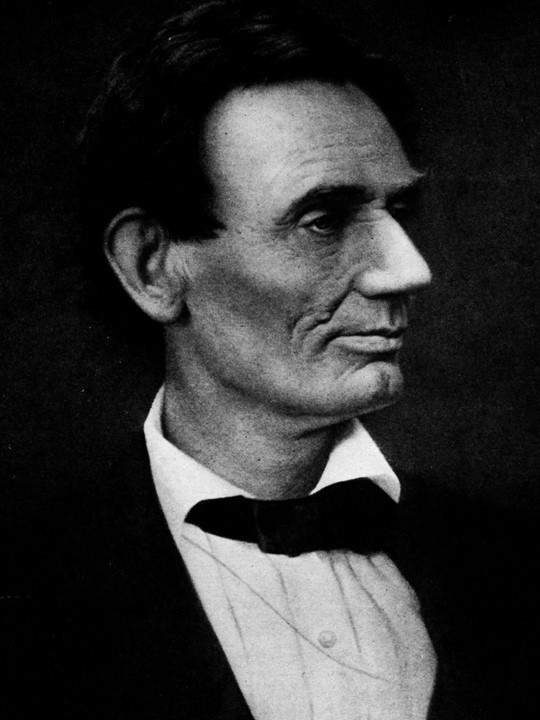

By the time he reached Quincy on that damp Wednesday morning, Oct. 13, 1858, Abraham Lincoln was exhausted.

Two weeks earlier, as Lincoln stepped off a train at the Great Western Railroad station in Jacksonville, Illinois College President Julian M. Sturtevant was stunned at how haggard Lincoln looked.

"You must be having a weary time," Sturtevant said.

Lincoln revealed that he had thought about quitting the race for Stephen A. Douglas' U.S. senate seat.

"I am (tired)," he said, "and if it were not for one thing I would retire from the contest. I know that if Mr. Douglas's doctrine prevails it will not be fifteen years before Illinois itself will be a slave state."

Lincoln was referring to Douglas' Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. It legalized Douglas' doctrine of popular sovereignty -- which allowed the residents of a territory to vote for or against slavery, and repealed the Missouri Compromise, which since 1821 had kept slavery south of Missouri's southern border.

Fatigued though he may have been, Lincoln felt compelled to continue the race to remind Illinoisans that the founders had put slavery on a path to extinction. He feared that Douglas' doctrine and the U.S. Supreme Court's 1857 ruling in Dred Scott v. Sanford that "the Negro has no rights which the white man is bound to respect" would enable the expansion of slavery.

"We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free," Lincoln said as he opened his campaign against Douglas in June, "and we shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State."

Douglas, 45, also was tired when he arrived in Quincy the night before his sixth debate with Lincoln. He had started his re-election campaign soon after Lincoln accepted his party's nomination with his "House Divided" speech on June 16, 1858.

Better organized and better funded, Douglas had the use of a luxurious private coach that Illinois Central Railroad President George McClelland provided. But he had conducted a whirlwind campaign. By the end of July, he had spoken in dozens of towns.

Through the early summer of his campaign, attorney Lincoln, 49, was preoccupied with several legal cases. He would not allow the campaign to interfere with his standard that he owed his law clients his best efforts. In June and July, he appeared 10 times before Judge Samuel Treat in the U.S. district court in Springfield and argued several more cases in Illinois circuit and supreme courts. It was August before he could devote his full attention to his campaign.

When he had time for appearances, Lincoln dogged Douglas around, usually speaking to audiences on the evening after a Douglas speech. That tactic did not last long. Douglas partisans suggested Lincoln was so weak he could not attract his own followers. One suggested that Lincoln join a circus to draw audiences. An embarrassed Lincoln abruptly canceled several appearances. In late July, he challenged Douglas to a series of joint debates around the state. Douglas did not like the idea. Sharing the platform would only serve to elevate Lincoln. But not to do so would open Douglas to criticism that he was afraid of Lincoln.

Douglas proposed joint debates in the state's congressional districts. Since they already had spoken in Chicago and Springfield, he would agree to seven joint appearances. He proposed Quincy, the largest city in the Fifth Congressional District, site for the sixth debate. Lincoln agreed.

For Douglas, the trip to Quincy that mid-October would be a homecoming. Gov. Thomas Carlin, himself a Quincyan, had in 1841 appointed Douglas circuit judge and associate justice of the state supreme court for the Fifth Judicial District, headquartered in Quincy. At 27 years old, Douglas remains the youngest Supreme Court justice in Illinois history. He lived in a small Greek Revival-style home at Third and York for six years. It was an easy walk from there to the colonnaded Adams County courthouse on Fifth Street, opposite the public square, where he presided as judge. In 1843, the region's voters elected him to Congress and re-elected him in 1844 and 1846. The Illinois General Assembly elected him to the U.S. Senate in 1847.

A cold, raw wind greeted Lincoln and Douglas at Knox College in Galesburg on Oct. 7 for their fifth debate. Despite the weather, an estimated 15,000 people heard them speak from the second-floor balcony on the east side of Old Main hall.

Neither man slowed. After Galesburg, Lincoln spoke in nearby Toulon, took the Peoria & Oquawka Railroad west, and on the afternoon of Oct. 9 spoke in Oquawka. He hightailed it across the river to speak at the Iowa State Fair in Burlington that night.

Iowa would not influence the Illinois Legislature's choice of senator, but Gov. James Grimes wanted to jolt Lincoln to "take the gloves off at Quincy." After a speech in Monmouth the next day, Lincoln left to speak in Macomb.

Douglas, too, was squeezing as much effort as possible into Western Illinois. The day after the Galesburg debate, Douglas spoke in Macomb, Plymouth -- where every resident turned out to hear him -- and that afternoon in Augusta. That night, his train stopped in Camp Point, where a large celebration honored him. The train pulled into Quincy at 9:50 p.m.

After a torchlight parade and dinner with friends, the senator spent the night at the lavish Quincy Hotel, just across Maine Street from where he would debate Lincoln the next day.

An elaborate Republican welcome, planned by attorney Abraham Jonas' Republican committee, interfered with Lincoln's plan to relax at the home of Orville and Eliza Browning at Seventh and Hampshire streets before the debate. Republican women hosted lunch. Ambivalent about Lincoln's focus on slavery, Browning found an excuse to be out of town on debate day.

The debaters got an unexpected half hour rest while workers repaired a platform railing that had collapsed. At 2:30 p.m. Douglas, then Lincoln, navigated the steps to the pine-planked platform to address the 12,000 people who awaited the sixth Lincoln-Douglas debate.

Reg Ankrom is a former executive director of the Historical Society and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources:

Ankrom, Reg. "Lincoln: I would quit the race...." Presentation, Morgan County Historical Society, Feb. 2, 2016.

Basler, Roy P. "The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 2, 1848-1858." (New Brunswick, N.J., Rutgers University Press, 1953), p. 467.

Collins, William H. and Cicero F. Perry. "Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois." (Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905), pp. 251-253.

Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln and Douglas: "The Debates that Defined America." (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008), pp. 236-237.

Holzer, Harold, ed. "The Lincoln-Douglas Debates: The First Unexpurgated Text." (New York: Harper Collins, 1993), p. 279.

Johannsen, Robert W. "Stephen A. Douglas." (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), p. 662.

"Julian M. Sturtevant: An Autobiography." Edited by J.M. Sturtevant Jr. (New York: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1896), p. 292.

Wells, Damon. Stephen Douglas: "The Last Years, 1957-1861." (Austin: University of Texas, 1971), p. 97.

Wilcox, David F. "Quincy and Adams County History and Representative Men, Vol. 1." (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1919), p. 467-470.

Zarefsky, David. "Lincoln Douglas and Slavery: In the Crucible of Public Debate." (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), p. 52.