Quincy outmaneuvers Columbus for courthouse

Willard Keyes had no intention of letting the judicial seat of Adams County get away from the settlement he and John Wood had established in 1822. So when three state-appointed commissioners arrived in April 1825 to site the Adams County seat, Keyes was ready for them.

Acting on a petition by Wood, the state legislature had created Adams County in January 1825. Illinois law stipulated that the judicial seat was to be situated as near the geographical center of the county as possible. That should have eliminated Keyes’ and Wood’s settlement on the far west side of Adams County as a candidate for the center of local government. But Keyes, whose original journal is owned by the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, was not going to abandon the courthouse without a contest. He developed a plan.

Keyes had arranged a reception for the state’s commissioners by three-fourths of the male population of Quincy at the time. They were Jeremiah Rose, shoemaker John Droulard, and Keyes himself. Wood was in St. Louis. After the welcome, the commissioners set off to find the county’s center. Keyes guided them. In his years here, Keyes had become expert in Quincy’s natural surroundings, and he used his knowledge of the area to work his plan. He led the commissioners on a route calculated to win their affection—or their surrender — for Quincy.

Keyes led the commissioners through briars, bogs, quagmires, swamps and quicksand (in an area around today’s Mill Creek and Marblehead) and through pits of snakes and a cave full of bats some six or seven miles east of the river bluff (Burton Cave). By their return late that afternoon, the commissioners were exhausted and disgusted.

The next day, Wood joined Keyes and his guests, now willing to look elsewhere. Keyes and Wood led the commissioners on another circuitous but more hospitable route to a spot at today’s Washington Park. There Commissioner Seymour Kellogg of Morgan County gratefully drove a stake into the ground and officially pronounced it site of the Adams County seat.

Agitation for a new court house in 1834 rekindled memories that the law required it to be centrally located in the county. Land speculators Stephen A. Douglas and two Jacksonville friends initially focused on the exact center of the county, a place they called Adamsburg,within the huge Military Tract. But when that property’s owners could not be found, attention turned to Columbus Township, just east. It was about 18 miles northeast of Quincy.

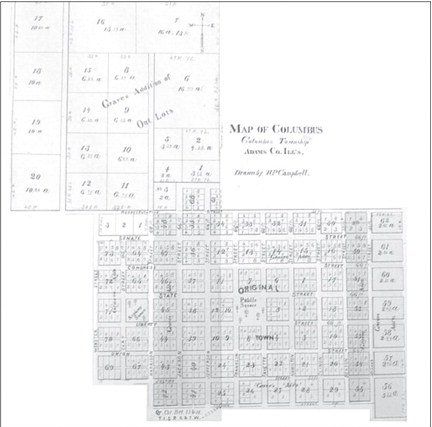

Almost overnight Columbus became a boom town. Businessman Willard Graves had the town laid out in 1835 and in the Feb. 5, 1836, issue of the Illinois Bounty Land Register advertised lots for sale. In the following year, settlers built 100 homes in Columbus, and Graves built a saw mill on McKee’s Creek. Easterner Daniel Harrison swapped eastern goods for commodities. Clement Nance and Thomas Castle opened general stores, and W.D. McCann operated a cabinet shop. The Bartholomews built the first corn mill.

By 1840 Columbus had a newspaper, the Columbus Advocate, with Abraham Jonas, a Quincy lawyer, directing editorial policy. Jonas’s aim was to make Columbus the county seat, and he and his neighbors got the question on the ballot. On August 2, 1841, the county’s voters elected to move county government from Quincy to Columbus by a vote of 1,636 to 1,545.

As soon as Justices of the Peace Henry Asbury and W.D. McCann certified the election’s results,however, attorneys representing several Quincyans alleged fraud and appealed to the Adams County commissioners to stay the results. Commissioners William Richards and Eli Seehorn, each favoring Quincy, issued the stay. Circuit Judge Stephen A. Douglas, appointed only months earlier to the local judicial district, invalidated that action. Douglas ordered the commissioners to obey the law, transfer county records and organize the county seat in Columbus.

Richards and Seehorn thwarted Douglas’s order by alternating their attendance at commission meetings. With Commissioner George Smith, who favored Columbus, always attending and either Richards or Seehorn attending, there was no concurrence for carrying out Douglas’s writ.

Douglas issued another order commanding immediate action, which Quincy attorney George Dixon appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court. Archibald Williams of southeastern Adams County argued Columbus’s position. Justices deferred their decision to their December session.

That gave Quincy time for another maneuver, this one to divide the county, with ten eastern townships going to a new county, Marquette, and the ten western townships remaining in Adams County. The Quincy group dared Columbus to support the measure, knowing that Columbians would have appeared disingenuous had they done so. Columbus proponents had justified their efforts to gain the county seat by complaining Quincy was nowhere near the county’s geographic center. In the way Quincy strategists drew the new county lines, Columbus was put in the same position—at the far west side of Marquette County. Columbus rejected the offer.

In February 1843 the legislature passed Quincy Rep. Almeron Wheat’s bill and created Marquette County. Residents of the new county called the new law despotic—they had not been allowed to vote on the separation — and refused to take part in any county affairs. As the law required, an election of Marquette County officers was held in April. Not a single vote was cast.

Judge Jesse B. Thomas, who succeeded newly elected Congressman Douglas, upheld a prohibition of Marquette voters taking part in Adams County affairs. Marquette had no county seat, no county services and even no law. There was at least one benefit, however: there was no county tax.

In 1847 the state legislature amended the boundary of the eastern county, changed its name to Highland County and aimed to establish county government, including tax collections. Still, residents of the new county refused to organize.

A fed-up Archibald Williams, who had been elected a delegate to the Illinois Constitutional Convention in 1847, dealt with the dispute by winning approval of a constitutional limit to how long a proposed county could remain unorganized. That should have ended the dispute once and for all. It was the end of Marquette- Highland County, but not the end of the story.

On Jan. 9, 1847, fire destroyed the courthouse on the east side of Fifth Street in Quincy. Once again, some outlying residents renewed the cause to move the courthouse nearer the geographic center of Adams County. This time it was Coatsburg that sought the county seat. But Adams County voters apparently had had enough — 7,238 of them voted to keep county government in Quincy and 3,109 voted for Coatsburg. Keyes had kept the courthouse in Quincy.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.