Quincyan’s Ancestor Signed Declaration of Independence

This space last week detailed the way in which the death of an ancestor of the late Quincy physician, Alcee Jumonville III, caused the French and Indian War. That event, the murder by Major George Washington’s British troops of French Ensign Joseph de Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville in the Upper Ohio Valley ignited an even more important occurrence in American history, the American Revolution. Quincy is directly connected to that history, as well.

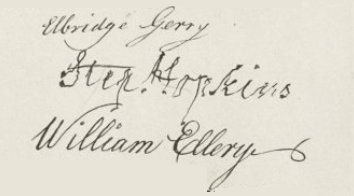

About halfway down the far right column of signatures on the Declaration of Independence is the shaky penmanship of Stephen Hopkins, the former ten-term governor of Rhode Island. At 69 years of age, Hopkins was the second oldest of the 56 men—Benjamin Franklin at 81 was oldest—who were signing their death warrants in declaring independence from Great Britain. Hopkins was a direct ancestor of the late David Sanders of Quincy, who for 33 years taught biology, microbiology, and zoology in Quincy schools.

Hopkins’s signature is easily recognizable. He suffered from palsy. In affixing his signature, he tried to control his quivering right hand with his left. Historians write that as he shakily signed the document, he said, “My hand trembles, but my heart is steady.” Here’s the Hopkins and Sanders story:

After the murder of 35-year-old French Ensign Jumonville near today’s Pittsburgh on May 27, 1754, the French and British fought seven years for control of the American continent. Great Britain won the war, secured its American colony’s borders, and acquired significant French territory in Canada and the Floridas. But the war left Britain heavily in debt, and British and Dutch bankers who financed the war were demanding repayment.

It was the way Britain proposed to pay down the debt that brought one of the first and one of the strongest protests in 1764 by Stephen Hopkins, governor of the British Rhode Island colony. The late David Sanders’s grandmother was born a Hopkins. It meant that Sanders, who died on November 29, 2017, also was related to Benedict Arnold, the Revolutionary War officer who rose to the rank of major general before defecting to the British in 1780. Arnold was Stephen Hopkins’s cousin.

Britain’s King George II believed that since the war saved American colonists from the French, the colonists should be responsible for the debt. The British Parliament in 1765 passed a Stamp Tax, the first direct tax on the colonists, which was assessed on every document printed or used in America. In addition, Britain began to post regular army units in America and required the colonists to pay for quartering them. Parliament next imposed duties on china, glass, lead, paint, sugar, and molasses imported from Britain. Most antagonizing was the Tea Act of 1773, which was designed not to raise revenue but to bail out the failing British East India Company. The act gave the company monopoly status for importing and selling tea in the colonies.

Hopkins was among the first firebrands for independence in the colonies. With his brother Esek, he had built and outfitted ships for American trade at Atlantic ports. The British required that goods be shipped only on British ships, which infuriated Hopkins. In 1744 he was elected to the Rhode Island General Assembly, served as an associate justice of the state supreme court from 1747 to 1749, and became chief justice in 1751.

In 1754 Hopkins attended a conference at Albany in 1754 at which Benjamin Franklin proposed an alliance of the colonies, which Hopkins supported. Franklin’s proposal failed, but the conference cemented a lifelong friendship of the two men called radicals in their day.

In 1764, Hopkins wrote a 25-page pamphlet, “The Rights of the Colonies Examined,” widely circulated in American and Great Britain, which condemned British taxation without representation. His colleagues knew him as a man fearless against the British where liberty was threatened. In an incendiary speech in 1774 to the First Continental Congress that colonial patriot Paul Revere recorded, Hopkins said, "Powder and ball will decide this question. The gun and bayonet alone will finish the contest in which we are engaged, and any of you who cannot bring your minds to this mode of adjusting the question had better retire in time."

Dave Sanders was in the line of ancestry whose generations from the time of Stephen Hopkins had been involved in American wars from the Revolution to World War II. Sanders and his brothers William and James, a bronze star winner, were World War II veterans. Their Uncle George Day served in World War I, and their father David fought in Cuba, one of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, during the Spanish-American War. Grandfather William V. Sanders was a Union Army lieutenant in the Civil War, and six great uncles were imprisoned at Andersonville during that test of national endurance. Great Uncle David Hopkins fought at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend under General Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812. David Hopkins’s father Ephraim, cousin of Stephen Hopkins, had been a minuteman in Boston in the war Stephen Hopkins helped to launch.

Sanders left high school before he finished his final semester in 1944 to join the Marine Corps. His high school awarded him the half-credit in American history he needed to graduate. He trained at San Diego and Ft. Pendleton and deployed as an electronic communications expert operating equipment that scrambled and decoded messages in his assignments in the Pacific. He was with the Sixth Marine Division when it reclaimed Okinawa.

When the Japanese sought peace in the Pacific after atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Sanders was aboard the battleship U.S.S. Missouri where he witnessed Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu and Supreme Allied Commander General Douglas MacArthur sign the treaty that ended the war in the Pacific and World War II. Sanders was discharged from the Marines in May 1946. Full military honors were conducted at his gravesite at Sunset Cemetery at the Illinois Veterans Home.

Sources

“David Sanders, 1926-2017,” Herald-Whig , https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/whig/name/david-sanders-obituary?pid=187417446

David Sanders, interview by Reg Ankrom, June 2, 2015.

Foster, William E. Stephen Hopkins: A Rhode Island Statesman. (Providence: Sidney S. Rider, 1884), 207.

Goodrich, Charles Augustus. Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence. (Murrieta, California: R.W. Classic Books, 2018), 166.

Hopkins, Stephen. “The Rights of Colonies Examined.” Booklet. Providence, Rhode Island, 1764.

Millar, John F. Stephen Hopkins, Architect of American Independence, 1707-1785 . (Newport, Rhode Island: Journal of the Newport Historical Society, Winer 1980), 31.

Sanderson, John. Sanderson’s Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence. Robert T. Conrad, ed. (Philadelphia: Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co., 1874) 200.

“Stephen Hopkins,” Society for the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, https://www.dsdi1776.com/signers-by-state/stephen-hopkins/

Stewart, Thomas C. “A shaky hand but steady heart.” Washington Times, July 3, 2017.